By: Ian Miller

Introduction

“Death in its ghastliest and most abhorrent forms, everywhere… All the fields and woods from the Emmetsburg road to the base of Round Top were one vast hideous charnel house.”[1] These are the words of J. Howard Wert, a civilian observer of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg. The battle lasted three days, from early July 1st until July 3rd, 1863, with Confederate forces retreating on July 4th. While many Americans may have celebrated that day, the people of Gettysburg remained too preoccupied with the status of their town to celebrate. Wert’s recollection of the battle, given on its 50th anniversary, embodies the state of Gettysburg after the battle, with both humans and nature critically wounded. The campaign, culminating in the Battle of Gettysburg left immense impacts on the environment and people of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Facing immense physical destruction of nature, landscape, and local agriculture. While current scholarship in the field of environmental history of the Civil War focuses on the Southern theaters of war, there is an opportunity for an extensive case study into the impacts that resulted from the largest Northern battle of the war. The Battle of Gettysburg was a short conflict, therefore, it allows for the examination of what impacts a shorter campaign has on the environment and agriculture of a region compared to those seen in the Southern theaters of war.

Overall, scholarship on the environmental history of the Civil War focuses on large-scale environmental destruction observed largely in Southern theaters. The portion of scholarship on the invasion of the North and Gettysburg focuses on niche topics, rather than a large case study encompassing multiple categories of environmental impacts. Through combining methods of the current scholarship focused on the large-scale destruction observed in the South and translating its focuses to a comprehensive study on the largest Northern conflict, the best understanding of a short campaign’s impacts can be revealed. Research on nature at the Battle of Gettysburg will reveal in what ways the Gettysburg region was impacted by the relatively short, but intense, Battle of Gettysburg. Additionally, it can expand current scholarship on the role of commonly investigated topics, such as the collapse of ecosystems, epidemic disease, the lasting alteration of lands, and the destruction of agriculture, to include the war’s largest battle. Finally, research into the aftermath of Gettysburg will explain how and why the region avoided the major environmental consequences that were often observed in the South.

The American Civil War and Nature: Current Scholarship

Current scholarship on the American Civil War focuses on exploring its social, political, and military aspects. Scholarship in the field of the environmental history of the Civil War has only begun relatively recently, leaving many topics open for further investigations. In studying wars, a new significance has been placed on focusing on their short- and long-term effects on nature. From battle to battle, Union and Confederate troops left scars across the nation both through and outside of combat, with their operations having resulted in disruptions from deforestation and man-made wildfires to ecological pollution and the crippling of agricultural systems across the nation.[2]

Lisa Brady’s War Upon the Land builds on her previous scholarly essay, “The Wilderness of War”, which emphasizes the use of fire as a weapon and way to control nature, along with the transformation of landscapes into wastelands in the wake of military operations.[3] Brady elaborates further on these topics through case studies from the western and Southern theaters, but not the northern one. From the exhausting effects military operations had on nature through travel and encampment, Brady discusses the impact the Civil War had beyond the battlefield. With this, Brady argues the targeting of Southern “agroecosystems”and landscape with “scorched earth” tactics as having resulted in large swaths of Southern agricultural lands being turned into wastelands.[4] The Southern agricultural system took time to be repaired after the war from the effects of the conflict, due in part to these tactics, as military operations left many Southern regions unfit for future cultivation in their wake.[5] In Gettysburg, sources do not point to large-scale ecological collapse, possibly due to the suddenness of the battle, paired with the lack of major military encampment before or following the battle.

Brady largely focuses on the South and military operations outside of battle, leaving room for research to be conducted on the specific impacts of combat and those in the North.[6] Because the fighting of the Civil War occurred largely on Southern soil, the majority of scholarship on the environmental impact of the war investigates the South. Brady’s focus on deforestation, ecological pollution, and the disruption of agriculture as a result of military operations can be applied directly to Gettysburg, which can contribute significantly to current Civil War environmental history.

Megan Kate Nelson, much like Brady, focuses on how military operations impacted the forests of both Southern and Northern theaters of war by looking at troop movements, army encampments, and the establishment of roads and bridges.[7] Whether trees were felled from battle or to supply lumber to keep the army moving forward, Nelson presents evidence through memoirs and of-the-era imagery on how armies destroyed them. Much in line with Brady’s work, Nelson discusses deforestation as a means to build roads and bridges. The Gettysburg Campaign is mentioned several times by Nelson, examining Culp’s Hill, Little Round Top, and other locations around Gettysburg, noting the impacts the battle had on trees there.[8] Nelson’s discussion of the damage to trees at Culp’s Hill is accompanied by several others on the same location within current scholarship, with an abundance of photographs available to illustrate the damage witnessed there. The rapid developments that led to the Battle of Gettysburg, and the absence of major military encampments before and following it, allows for a contrast to be seen against Nelson’s investigations into longer, more intensive Southern campaigns. Without long-term major military encampments at Gettysburg, less of a need was placed on lumber and the clearing of areas for roads to be built, both of which were significant factors for the destruction observed in the Southern theaters.

As described by Minshall and Brady, agriculture suffered catastrophic damages following military operations in the Civil War, which has shaped a historiography of Civil War environmental history that focuses largely on agriculture. Erin Stewart Mauldin discusses investigations into the exhaustion of Southern agricultural regions as a result of the Civil War. In Unredeemed Land, Mauldin argues that although military operations had large, visible impacts on the landscape, they also served to accelerate smaller, long-term negative changes in the land.[9] She discusses impacts through contamination, pollution, and overall degradation of soils, using Nineteenth Century soil assays and geological reports from the following decades. Mauldin points out the influences the war had on the environment following its conclusion, especially how freedoms for Black individuals altered labor and land management practices.[10] As the Southern agricultural system no longer had an unimpaired and free labor force, the maintenance of current agricultural lands began to decline, along with the felling of forests for new fertile farmlands.[11] Both of these factors coincided with an increased reliance on harmful chemical fertilizers to counterbalance the exhaustive nature of cotton and tobacco farming.[12] Investigations into Gettysburg can be conducted following Mauldin’s methods of investigating farms with a focus on post-battle impacts. These investigations will look at how other factors, like battle clean-up, town recovery, treatment of wounded, and other non-combat topics impacted the nature of Gettysburg.

Historians like Kathryn Meier have begun looking at the impacts nature and humans have on one another, particularly how human actions resulted in the spread of disease. This relationship between human and military actions outside of battle can help explain why Gettysburg suffered less environmental damage and less epidemic disease than many Southern theaters. Meier’s investigation into disease stemming from military operations, specifically illnesses such as cholera and yellow fever, reveals the significant role of disease in Civil War environmental history.[13] Meier’s attention to sickness stemming from nature as a result of militaries is a focal point for an investigation into Gettysburg. As of now, there are no recorded epidemics in the Gettysburg region following the battle. Because of the lack of large-scale illnesses borne of military operations in the North, a comparison on why the South suffered outbreaks and Gettysburg did not will advance the scholarly discussion.

Rather than focusing solely on the impact battles may have had, Meier expands into investigating how troop movement, military encampments, and the actions of soldiers as individuals, rather than armies as single entities had on the environment. Importantly, Meier focuses on the impact soldiers had on the flora and fauna across theaters of war, through discussions on the killing of wildlife by soldiers, the resources and efforts required to set up military encampments, and the draining effects of military encampments on the environment.

Meier’s work offers the opportunity to draw conclusions on why mass sickness did not occur through the discussion of sanitary practices at Gettysburg. Much like most scholarly works on this topic, Meier’s focus on a specific time and place, 1862 Virginia, limits what can be pulled from her work, but still, such an extensive Southern case study can provide helpful comparison for a Northern one. Why did Gettysburg avoid any epidemics, even as thousands of men and horses remained unburied for weeks following the battle there? How did the sanitation efforts of the people of Gettysburg allow for the avoidance of an epidemic? Accounts claim that the heavy rains along with extensive use of chemicals following the battle helped cleanse the land and therefore prevent disease.[14] But these rains were also reported to have swelled and flooded locations abundant with corpses, a process that contaminated drinking springs.[15] This could lead someone to expect further contamination of water sources as time went on and corpses remained an issue, yet local newspapers at Gettysburg reported no mass sickness. Official reports on casualties between Union and Confederate forces show almost no mention of disease as a killer at Gettysburg.[16]

Offering more discussion on disease and impacts at Gettysburg, Gregory Coco gives an understanding of how civilians dealt with the aftermath of battle, avoiding both epidemic and mass environmental impacts from thousands of hasty burials. Relying on civilian accounts, he discusses the hasty burial of the corpses of thousands of soldiers, along with how civilians secondarily dealt with the removal of the animal corpses littering the battlefield.[17] While a focus was placed on the removal of human corpses first, Coco explains that conservative estimates put the total weight of dead humans, cows, horses, mules, oxen, and pigs at Gettysburg at around approximately six million pounds.[18] With this much to bury or remove, and a large portion of it left as a secondary concern, the amount of decomposition that occurred in the aftermath could have posed health risks to local populations. What can be seen through the accounts collected by Coco is that the people of Gettysburg appear to have been efficient in their response but overwhelmed. While Coco focuses on how the aftermath of the battle changed the lives of the civilians of the town and region, accounts and photographs within A Strange and Blighted Land, reveal the impact of expansive hasty burials, along with suggesting how Gettysburg avoided an epidemic.

Aftermath and Burials

The Battle of Gettysburg was the largest battle of the American Civil War; hence it brought with it the largest number of casualties, leaving the number of wounded and dead in incredible quantities across the Gettysburg area. Consequently, the scale of destruction on the environment expanded beyond just the visible, initial, damages of battle. The scale of human destruction was widespread, with approximately 7 million rounds of ammunition fired across the three day battle. A rough estimate given by medical officers of the era included 40,200 wounded and killed between the two armies, with approximately 10,000 killed.[19] Sources on the magnitude of casualties vary, but often fluctuate between the historical value of 40,000 to the modern one of approximately 51,000 killed, wounded, and captured. Beyond just soldier losses, each army brought with it tens of thousands of horses and military animals, which contributed to the roughly 3,000 horse casualties during the battle.[20] Historian Robert L. Bloom summarized the desolate scene in the wake of battle, positing that, “By far the most distressing aftermath of the battle were the thousands of dead, dying, and wounded men left behind by the departing armies. Of the approximately 170,000 troops at Gettysburg, one of every four was a casualty: killed, wounded, or reported missing. How many of the more than 27,000 wounded survived the rough surgery and the less than skilled nursing care is uncertain.”[21] A positive was that Gettysburg sat outside of enemy sights following the stunting of the Confederate invasion of the North. This allowed for relatively safe supply chains and transportation to be established, but dealing with the remnants and casualties of battle still represented a substantial task.

The thousands of dead men and horses in the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg left those involved in the post-battle recovery faced with a difficult decision; to destroy their lands with thousands of rapidly dug, often inefficient graves for the immense number of casualties, or run the risk of sparking rampant disease borne of exposed carcasses. The community of Gettysburg, acting largely through pre-emptive sanitary actions following the battle, chose the former. A Pennsylvania army lieutenant present in the direct aftermath of the battle, John Howard Wert understood the necessity of burying corpses rapidly at the expense of the environment as, even more so than those of deceased soldiers, the approximately 3,000 unburied horse corpses rotting brought risk of disease and death.[22] So many horse corpses remained in the aftermath of battle that even following the institution of disposal through mass burnings, excess bones remained in such an abundance that farmers began grinding them to use as fertilizer for their damaged fields.[23]

While combating disease, the crude graves did not adequately address public health concerns at Gettysburg, and this resulted in notable environmental damage as well as the continued threat of epidemic. Wert conveys the destruction he observed at the Rose Farm nearby Plum Run Creek:

…nearly one hundred rebels were buried. All around the barn, even within the house yard, within a few feet of the doors, were, in numbers, the scantily buried followers of the Confederate cause. Two hundred and seventy-five were buried behind the barn; a rebel colonel [Hance, 53rd Georgia] was buried within a yard of the kitchen door. No pen can paint the awful picture of desolation, devastation and death that was presented here to the shuddering beholder who traversed these localities July 4, 5 and 6, 1863…[24]

John Blair Linn, a civilian in the town during the aftermath, describes the scene at the Rose Farm much like Wert, claiming that Mr. Rose’s farm was claimed by rebel graves, with dozens more soldiers laying unburied in his wheat field.[25] Mr. Rose claimed to have removed the corpses of ten rebel officers and left them in a nearby ravine to avoid the contamination of his well.[26]

Accounts of the aftermath of Gettysburg tend to coincide on indecisiveness in the turmoil that followed the battle, with worried farmers removing hastily buried corpses. This negatively impacted their farms and renewed the risk of disease. Almost two weeks after the closure of the battle, The New York Times’ correspondents in Gettysburg reported that just at that point the final corpses were being buried. Even weeks after the battle, corpses of humans and horses were still being rapidly buried, some right where they had fallen in graves just shallow enough to roll them over into.[27] The scarring of the landscape of Gettysburg with graves of Union and Confederate forces served as a major impact on the environment. While rapid burials alleviated some concern over the spread of disease across the region, the ineffective nature of the graves resulted in many soldiers being posthumously removed, or revealed through natural means, leaving disease as a looming threat.

Disease and Sanitary Efforts

In the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, the scene was set for an outbreak of mass illness and a possible epidemic following the contamination of water and soil resources by corpses. Outbreaks of mass sickness stemming from military operations, which occurred frequently in southern theaters, are a new focus in regards to the Civil War. As armies moved throughout regions, they dug entrenchments, fouled water supplies, and left soils contaminated with waste, resulting in soldiers and animals dying at high rates.[28] The pollution of water systems reached extreme points in the Shenandoah Valley, with an average of 162 soldiers per thousand being afflicted with illness related to tainted water.[29] However, Gettysburg itself did not experience a major epidemic following the battle, despite the mass death that occurred there. So how did the people of Gettysburg avoid epidemic following the battle?

The health and spirits of the wounded at Gettysburg were aided by the vast quantities of food, medicine, and clean clothing distributed to them.[30] Following the battle, Gettysburg was safely outside of the scope of combat, and medical staff noted the abundance of resources made available to help the wounded as a result of secure supply lines.[31] Medical officer John S. Billings claimed that during his care of the wounded, the Sanitary Commission constantly supplied the wounded with fresh vegetables, bread, and importantly, oranges.[32] Union troops, and to a lesser extent Confederates, found themselves well taken care of, as noted by Chaplain William C. Way at Camp Letterman, a field hospital housing the wounded of both sides. Way posited in a letter from Gettysburg in 1863 that, “A fine spring, sufficient for a bountiful supply of good water is located near the cook”, going on to claim, “The patients are in good spirits.”[33] Because of the efficiency in supplying field hospitals with medical supplies and nutritious food, paired with adequate care for the wounded, hospitals did not form into major sources of disease. With the medical staff adequately addressing risks of disease from the wounded, the people of Gettysburg could focus their efforts on reducing the risk of disease from corpses.[1]

As historian Jack Temple Kirby summarized in his ecological view of the Civil War, “Whenever a predominantly rural people are suddenly and densely brought together in encampments and cities, as they were in 1861, they exchange pathogens and, lacking immunities, many sicken, and many die,” with this passing of pathogens also expanding to civilian and military animals.[34] Much like Wert and Linn gave their accounts on the magnitude of inefficiently tended-to corpses following the battle, an account from Thomas Knox writes that at one point in traveling between Little Round Top and Seminary Ridge, he observed fifteen bloated, rotting horse corpses littering the grounds of a family orchard, with no effort made to bury them.[35] One civilian, Sallie Broadhead, noted the air of the town as “…loaded with the horrible smell of decaying horses and the remains of slaughtered animals and, it is said, from the bodies of men imperfectly buried,” having further noted that the stench of death brought with it the fear of disease.[36]The scale of the required work to effectively address corpses following the battle appeared too much for the people of the town to handle.

Even as corpses remained polluting the air and resources of the town, no mass illnesses or epidemics were reported in Gettysburg following the battle, and this was in part due to the preemptive sanitary actions taken by the town. Sources have placed the range of wounded at Gettysburg around 14,000 and 15,000-18,000 for Confederate and Union forces respectively, representing thousands of individuals susceptible to disease.[37] The large number of corpses present in the aftermath of battles of the era often sparked cholera outbreaks through water contamination. Yet, in their report on the casualties of the war in 1870, the United States Surgeon General’s Office reported only around a dozen deaths between both Union and Confederate casualties wounded at Gettysburg as having been related directly to an illness, usually tetanus, cholera, meningitis, pneumonia, and variola (smallpox).[38] This, paired with the general lack of reports on sickness throughout the civilian population following battle, raises the question as to how the carnage of Gettysburg did not result in epidemic.

Unlike the extensive campaigns studied by Meier in the Virginias, and Brady in the Carolinas and Deep South, the Gettysburg Campaign was relatively brief. The three day Battle of Gettysburg concluded quicker than sieges in the South, with the Siege of Vicksburg lasting 47 days, and the Siege of Petersburg 292 days. Less exposure to the dead, wounded, or possibly-contaminated drinking water sources meant less likelihood for the transmission of disease. The fact that Confederate troops retreated back into Virginia within days after the closure of battle, and Union troops left the area within weeks, eliminated the spread of illness locally through major encampments.

In addition to the briefness of the Gettysburg Campaign, the actions of civilians at Gettysburg in cleansing the town in the week following the battle aided in the prevention of an epidemic. A Gettysburg resident, Nellie Aughinbaugh claimed that the only thing that saved the town from an epidemic was a notable heavy rain that came about on the third day.[39] These heavy rains were verified by Billings, who also noted heavy rains beginning the day after the battle, which lasted for five days and nights.[40] Beyond the rains, as noted by Bloom, chloride of lime was used so often to cleanse the streets of the town that, “…she [Aughinbaugh] found it unnatural ‘when we smelled it no longer.’”[41] Additionally, shortly after the conclusion of the battle, the newspapers of Gettysburg were calling upon locals to, “…provide horses, wagons, and manpower to help “bury the dead and to cleanse the streets in such a thorough way as to guard against pestilence”.[42] The long-lasting rains, partnered with the extensive use of chloride of lime and sanitation efforts by the civilians of Gettysburg worked in combination to combat the emergence of an epidemic.[2]

While military operations’ ability to spread disease is a major factor of the environmental history of the Southern theater of war, Gettysburg avoided this through careful sanitary actions, natural means, effective supply lines, and due to the timeline of the Gettysburg Campaign. While Gettysburg did not experience this major impact of war on the environment, it did share the widespread destruction of the landscape seen in the South. Much like the destruction of “agroecosystems” and the Southern landscape and agriculture as described by Brady and Mauldin, the lands of Gettysburg suffered. From the battle itself, and the extensive burials conducted across the battlefield, the lands and agriculture of Gettysburg were under intense attack throughout 1863.

Farms and Agriculture

The widespread destruction of agriculture observed by Brady and Mauldin in the Southern theater of the war, while incredibly extensive, was not isolated to that region. The Battle of Gettysburg left local farms in ruin, riddled with scars and rapidly dug graves whose impact lasted long after the fighting ended. In Southern theaters, farmers found their fields and orchards the specific targets of Northern forces through “scorched earth” tactics, but agriculture at Gettysburg was both a target and the resting place of invading forces.

The resulting destruction at Gettysburg was visible and extensive. In his previous recollection on his observations at the Rose Farm, Wert described the sprawling expanse of graves present across the family’s farm, hindering farm activities and threatening water supplies with contamination. Further on in his account of observations at Gettysburg, Wert explains how the “Fences and fruits of the earth had alike disappeared before the withering besom of destruction,” which left the fields of the town a wasteland.[43]

Civilian Robert McClean wrote in a letter following the battle that artillery movements “Made roads over the grain fields, destroying fences, injured the barn, and did other damages,” damages that appeared more topical, but would serve to impede agriculture for some time following the battle.[44] The simple destruction of fences and rock walls, while not appearing as substantial environmental consequences, resulted in many families’ farm animals being let loose. Throughout and following the battle, cows, hogs, sheep, and horses all wandered the region, with many perishing during the battle, and others never returning to their farms.[45] Destruction covered a wide expanse of the Gettysburg region, as civilian Harriet Bayly put it, “…at least twenty miles of country lying close around the town were taken up by the manifold and murderous agents of the fight: men, horses, canon, wagons, ambulances and hospitals.”[46] The widespread destruction of crops and farm implements crippled the agriculture of Gettysburg, and the immense burden of burying corpses further slowed the remediation of farmlands.

Returning after the battle, Brian’s home bore the damage of artillery and heavy small arms fire, with his fields and farm fencing heavily damaged.[47] Expanding Brian’s experience, Bloom’s work on civilian accounts following the Battle of Gettysburg includes the account of a “Widow Leister”, who claimed:

They got two ton of hay from me. … I’d put in two lots of wheat that year and it was all trampled down and I didn’t get nothing for it. I had seven pieces of meat yit, and them was all took. All I had when I got back was jest a little bit of flour yit. The fences was all tore down.. . . and the rails was burnt up. One shell came in under the roof and knocked a bedstead all to pieces for us. There was seventeen dead horses on my land. They burnt five of ’em around my best peach tree and killed it. . . . The dead horses spi’led my spring, so I had to have my well dug.[48]

Leister’s claim summarizes the loss experienced by farmers at Gettysburg. Not only was the harvest of that year spoiled, much like Abraham Brian suffered, but the damage that occurred to farm properties like Leister’s across Gettysburg would pose a hindrance for times to come. Leister too experienced the burden of dead horses on her land after the battle, which spoiled her drinking water, and posed an increased threat of disease. The destruction witnessed by farm families was often widespread, with both superficial wounds and more long-lasting damages to their lands.

One of these families was the Sherfys family, who owned a farm adjacent to the famous Peach Orchard, at the foot of the Roundtops, and which suffered heavy damage throughout the course of the battle. Following the battle, the damage to the Sherfys farm amounted to the complete destruction of their barn, much fencing, and their hog stables.[49] With this, the family lost three calves and a cow, along with a hog during the battle, and the felling of the majority of their new peach orchard, and heavy damage to the mature portion of the orchard.[50] Beyond the loss of farm property, the family noted that by the end of the battle, many soldiers had already been buried in shallow graves across their land, accompanied by the unburied rotting corpses of horses, made worse by the heavy rains of July 4th.[51] Finally, as a superficial damage to top it all off, Confederate artillery guns had left deep ruts into the grounds throughout their property.[52] With the Sherfys’ farm being located centrally to the Battle of Gettysburg, the family suffered a combination of almost every environmental impact investigated at Gettysburg.

The seizure and destruction of farm animals posed a direct, but remediable threat to the agriculture of the Gettysburg region. If fire had been used as a weapon like it was by the Union in the South, the region could have suffered an incredible loss of agriculture and nature. Some of the major impacts on the Southern agriculture and environment during the Civil War came from the “scorched earth” tactics utilized by Union generals Sherman and Sheridan in the South as outlined by Brady.[53] While Brady outlines the specific targeting of agriculture and nature with fire, Nelson points out that the use of fire in military operations often resulted in the unintentional destruction of the environment as fires spread out of control.[54] Earlier at Wrightsville, General Early witnessed the partially uncontrollable destructive nature of fire, as his tactic of burning bridges resulted in the unintentional destruction of a portion of Wrightsville. He wrote in his report, “The bridge was entirely consumed, and from its flame the town of Wrightsville caught fire and several buildings were consumed, but the further progress of the conflagration was arrested by the exertions of Gordon’s men”, illustrating the risks associated with fire as a weapon.[55] General Early wrote having claimed that the Georgians of Gordon’s men understood the destruction fire brought as it too destroyed part of their town of Darien.[56]

Seeing the towns of York and Gettysburg as at the financial and physical brink, General Early claimed to have refrained from excessive demands and the burning of buildings in “good will” towards the towns.[57] In his assessment of the town of York during the Gettysburg Campaign, Early wrote to the community, “I have abstained from burning the railroad buildings and car shops in your town, because, after examination, I am satisfied the safety of the town would be endangered… I do not desire to involve the innocent in the same punishment with the guilty,” with this reasoning of his having been applied to Gettysburg as well.[58] Much like the precautionary sanitation efforts in Gettysburg following the battle protected the area from epidemic, the consideration of how the mass use of fire may have damaged the local town helped alleviate collateral damage to the environment.

Not only did Gettysburg’s agriculture suffer from hundreds of hastily constructed graves embedded in farms across the battlefield, but the mass amounts of supplies and debris of battle littered the area as well. The clothes and remnants of felled soldiers laid in abundance across local farms, accompanied by discarded weapons, munitions, and supplies.[59] The Sherfys family claimed that remnants of battle, along with abundances of possessions of the Gettysburg residents littered their farms.[60] Litter from battle across the farmlands of Gettysburg, drew cleaners and scavengers to the battlefield for years to come, extending the lifespan of their impact. News correspondents in Gettysburg following the battle reported several thousand visitors being drawn to the town daily, coming out to aid the recovery of the town and wounded, out of curiosity, or in order to scavenge the battlefield.[61] These scavengers of the battlefield in turn acted as cleaners, reportedly removing gear and debris daily worth thousands of dollars at the time.[62] The immense number of individuals scavenging and exploring the area following the battle would remain a mainstay of the area into the present day. That being so, even several years following the battle, litter remained strewn across the landscape of Gettysburg, with Union Army Lieutenant Colonel Henry Boynton noting the condition of Emmitsburg Road and the streams around it in a visit to Gettysburg in 1866. In his account on the conditions there, Boynton noted that many relics of battle laid strewn across the Adams County countryside years later, particularly clothing, weapon fragments, military supplies, and discarded trash.[63]

Nature and the General Landscape

Across the hills, fields, and creeks of Gettysburg, the visage of destruction post-battle was present to visitors, as the Battle of Gettysburg left deep scars across the landscapes of Gettysburg. Nurse Sophronia E. Bucklin recorded what she witnessed at Culp’s Hill, positing that, “Every advantageous position was marked with torn turf, lopped tree boughs, and the graves of the slain. Indeed, our whole way was lined with the narrow strips of earth, which rested over forms gashed with the implements of carnage…”.[64] In recounts of the battle, along with scholarly writings on Gettysburg, witnesses and authors put a focus on the destruction at Culp’s Hill, where the destruction of both human life and the environment was heavy. The destruction Bucklin witnessed was reiterated by Thomas Knox, a witness of the battlefields of Shiloh and Chickasaw Bayou as explained by historian Gregory Coco.[65] Knox compared the destruction at Culp’s Hill to previous scenes he had witnessed, having claimed:

…the traces of the fighting there [Shiloh and Chickasaw Bayou] are but slight compared to those on this [Gettysburg] ground. I find tree after tree scarred from base to limbs so thickly that it would have been impossible to place one’s hand upon their trunks without covering the marks of a bullet… The storm of bullets must have been as thick as hailstones in an ordinary storm.[66]

Wert offered a more detailed account of the destruction at Culp’s Hill, having written:

None who saw it can ever forget how the trunks of all the trees… were riddled from the ground up, for twenty feet, so that scarcely a vestige of the original bark or its color could be seen… No pen can describe the appearance of these woods. Those who did not see the wonderful sight can never realize it. The life was shot from every pore of these trees as effectually as from the men in gray who were piled beneath them. The latter were buried in wide, yawning trenches all along that marshy valley as it extends toward Rock Creek…The former [trees] quickly rotted and were prostrated by every wind upon the graves… Neither man nor tree, that stood before the…[rifle] fire that swept the valley of death, could live.[67]

Wert’s description of the scarring of trees from rifle fire, along with the desolate scene of mass burials, emphasizes the draining of life from both man and nature as the ecosystem around Culp’s Hill collapsed. Coco cites him as further explaining how an entire forest was killed, with trees simply annihilated by battle.[68] The destruction witnessed by Knox and Wert at Culp’s Hill was extensive, and their accounts clarify why Culp’s Hill has become a major focus point in scholarship, conveying the damage to both human life and nature at Gettysburg.

Beyond damage from the events of the battle itself, the removal of vast field hospitals too exhausted the landscape of Gettysburg. Upon the removal of the Camp Letterman General Hospital at Gettysburg, nurse Bucklin wrote, “The hospital tents were removed—each bare and dust-trampled space marking where corpses had lain after the death-agony was passed, and where the wounded had groaned in pain. Tears filled my eyes when I looked on that great field, so checkered with the ditches that had drained it dry.”[69] The scene witnessed by Bucklin expanded across Gettysburg, as over two-dozen field hospitals operated during and following the battle. The remnants of these medical stations, along with the burials that occurred at them, as noted previously by local farmers, exhausted the nature and agriculture of the town. Following all of this, artists of the era were quick to photograph the damages to nature as explained by Knox, Wert, Bucklin and other witnesses.

Because of the national interest in Gettysburg, and the link formed between the loss of nature and human life there, there exists extensive photography of the destruction of the trees at Gettysburg. Modern scholarship, like that of Maura Lyons’, “An Embodied Landscape: Wounded Trees at Gettysburg”, focuses on this photography in a way that emphasizes more on the symbolic meaning of the damage rather than in an environmental health focus. As Lyons argues, because of the link between the death of nature, and those deaths of the men that fought below its trees, as perpetuated by artists and media at the time, extensive photographs were collected of environmental damage.[70]

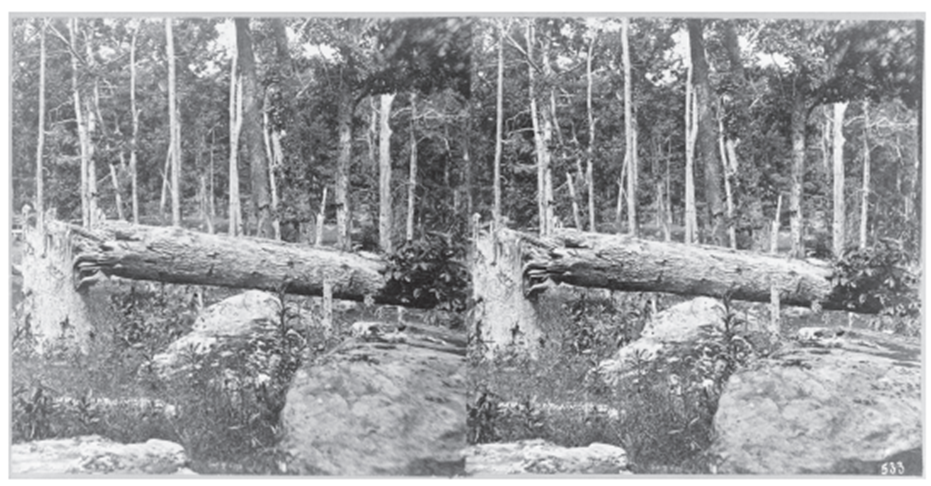

Figure 1 (Above): Battle-field of Gettysburg-Effect of Union Shot and Shell on the Trees on Culp’s Hill. Stereograph showing the damage to trees at Culps Hill, between 1868-1880.[71]

Following the Battle of Gettysburg, prominent photographers of the era flocked to the battlefield to capture the aftermath, which included Mathew Brady. In his stereographs, Brady captured the damage caused to the nature around Culp’s Hill from shot and cannon, seen in Figure 1.

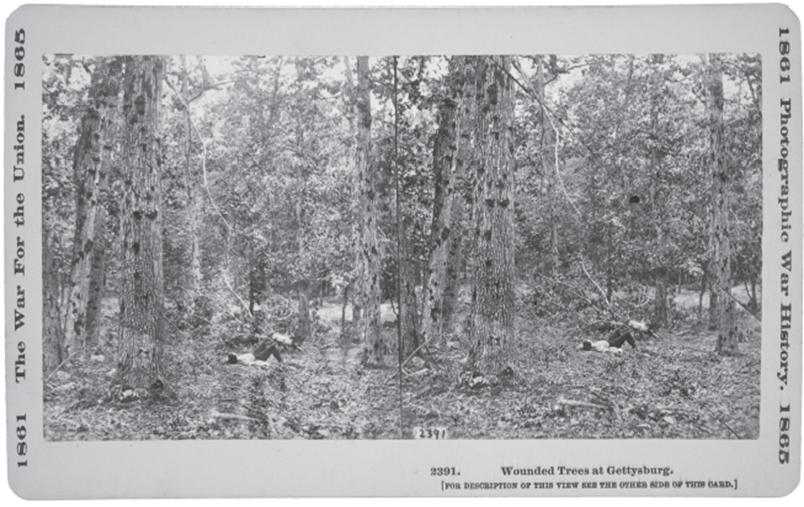

The stereograph above shows a glimpse into the felling of trees that occurred during the artillery battle between Union and Confederate forces across the eastern end of the Federal line at Culp’s Hill. The heavy guns of each side of the conflict were complimented by heavy small arms fire, with the several millions of rounds fired throughout the three day battle having stripped the bark and life away from trees across the battlefield. Figure 2 below shows such scarring of trees left from the weapons of Union and Confederate forces on the trees at Culp’s Hill; furthermore, Figure 3 shows a more widespread destruction and scarring of trees before the Union breast works of the eastern portion of the line.

Figure 2 (Above): Wounded Trees at Gettysburg. Stereograph depicting damage to trees at Culp’s Hill, 1863.[72]

Figure 3 (Below): Battle-field of Gettysburg – Union breast works on Culp’s Hill, temporarily taken by the Rebels. Stereograph showing damage to Culp’s Hill, between 1868-1880.[73]

These photographs are significant as they allow environmental impacts of historical war to remain visible into the modern day, preventing the lasting impacts from being forgotten. Over time, damage can become less visible and become overlooked as nature reclaims its lands, effectively “masking” the destruction, and extent of persisting impacts on nature.[74] Ignorance of these impacts can be dangerous. Throughout the Civil War, thousands of musket balls composed of toxic lead embedded themselves into trees. Though the tree may heal around the initial wound, the presence of lead can lead to long-term physical and biochemical issues to the ecosystem. The presence of these masked musket balls within the trees of Gettysburg is shown in Figure 4, depicting a portion of a “witness tree” with a Minié ball embedded within it.

Figure 4: Section of Witness Tree recovered from Culp’s Hill, Gettysburg, 2011.[75]

The lasting presence of these toxic munitions within the trees and soils of Gettysburg posed, and possibly still could pose, risks to the health of plant, animal, and human life in areas that experienced high volumes of gunfire during the battle.

Conclusion

The town of Gettysburg and the surrounding region suffered greatly throughout the course of the Gettysburg Campaign, with the influences on nature persisting for years in the aftermath of battle. The town suffered the loss of a season’s harvest and the destruction of farm property and implements. The land throughout the area was scarred by the extensive construction of rapidly dug, shallow, inefficient graves for men and horses alike. These graves, partnered with the mass amounts of decomposing carcasses across the battlefield, set the scene for an epidemic in Gettysburg, yet none emerged. The efforts of the civilians of Gettysburg and the local area along with medical officers and field hospitals were aided by the Sanitary Commission, strong supply and transportation lines, and the intervention of nature. This allowed the town to employ extensive precautionary sanitation practices and avoid epidemics of cholera and disease born of the corpses and aftermath left by the battle.

In Southern theaters, soldiers camped, marched, and fought for longer, and disease was a large contributor to civilian, soldier, and animal casualties. Unlike longer and geographically larger Southern battles, the Battle of Gettysburg lasted only three days. Following the battle, Confederate forces retreated back into Northern Virginia within days, and Union forces withdrew shortly thereafter. Still, the effects war leaves on the environment is seen heavily at Gettysburg, showing that historical wars, not just modern ones, should be a focus of environmental history going into the future. The Battle of Gettysburg shows both the optimistic victories and the brutal losses that can be experienced by a town and environment during the course of a war and remains today a source of extensive knowledge into the war and nature.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“A FIELD HOSPITAL AT GETTYSBURG.: Establishing the Hospital. Preparing for Night. A Change of Location. The Removal. After the Battle.” The Youth’s Companion (1827-1929), 64, iss. 27 (Boston, Massachusetts) Jul. 2, 1891. American Periodicals. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/127071823/AEF19E4A2113412FPQ/31?accountid=29140.

“A WEEK AMONG THE WOUNDED AT GETTYSBURG: II Incidents, Sabbath Services in

the Hospitals.” Christian Inquirer (1846-1864), 17, iss. 46 (New York, New York) Aug. 15, 1863. American Periodicals. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/135707556/AEF19E4A2113412FPQ/1?accountid=29140.

Battle-field of Gettysburg – Union breast works on Culp’s Hill, temporarily taken by the Rebels.

1868-1880. Stereograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-117888, Tipton & Myers’ stereoscopic views series, No. 537. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97507623/.

Brady, Mathew. Wounded Trees at Gettysburg. 1863. Stereograph. Library of Congress,

Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-steoe-2s02672, Civil War Photograph Collection, No. 2391. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011649197/.

Early, Jubal A. “General J. A. Early’s Report of the Gettysburg Campaign: March from

Fredericksburg. Capture of Winchester. March from Winchester into Maryland and Pennsylvania, and Operations until the Battle of Gettysburg. Battle of Gettysburg. The march from Gettysburg, Recrossing the Potomac, and return to the vicinity of Orange C. H.” Southern Historical Society Papers (1876-1905) 10, iss. 12. (Richmond, Virginia), Dec. 1882. Southern Historical Society. American Periodicals. Accessed March 31, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/137873371/AEF19E4A2113412FPQ/8?accountid=29140.

Ewell, Richard S. “General Ewell’s Report of the Pennsylvania Campaign: To Culpeper and Winchester. Berryville and Martinsburg. Crossing the Potomac and march to Carlisle. Expedition to York and Wrightsville. Gettysburg. Back to Darksville. Summary. At Winchest. At Gettysburg.” Southern Historical Society Papers (1876-1905) 10, iss. 7. (Richmond, Virginia), Jul. 1882. Southern Historical Society. American Periodicals. Accessed March 31, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/137869521/AEF19E4A2113412FPQ/9.

“OUR GETTYSBURG CORRESPONDENCE: The Last of the Dead Buried—Condition of the

Wounded—The Battle-field and Relic Gatherers.” New York Times (New York, NY), Jul. 15, 1863. American Periodicals. Accessed March 26, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/docview/91768717?pq-origsite=summon.

“Section of Witness Tree recovered from Culp’s Hill, Gettysburg, 2011, with embedded Minié ball”. 2011. Photo. Gettysburg National Military Park, in in Maura Lyons. “An Embodied Landscape: Wounded Trees at Gettysburg.” American Art 26, no. 3 (Fall 2012), 44-65. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669222?pq-origsite=summon&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Tyson, C.J. Battle-field of Gettysburg-Effect of Union Shot and Shell on the Trees on Culp’s Hill. 1868-1880. Stereograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-117889. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97507634/.

United States, Surgeon-General’s Office. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-65) 2, part 1 (Washington, D.C.), 1870. NLM Publications and Productions. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections. National Library of Medicine. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-14121350RX4-mvpart.

Winslow, Gordon. “The Wounded at Gettysburg.” Medical and Surgical Reporter (1858-1898) 10, iss. 14 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Aug 1, 1863. American Periodicals. Accessed March 27, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/136431827/B4B0EB5D47D74A45PQ/3?accountid=29140.

Secondary Sources

Bloom, Robert L. “”We Never Expected a Battle”: The Civilians at Gettysburg, 1863.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 55, no. 4 (Fall 1988), 161-200. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27773262?Search=yes.

Brady, Lisa. “The Wilderness of War: Nature and Strategy in the American Civil War.” Environmental History 10, no. 3 (2005), 421-447. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3985998.

Brady, Lisa. War upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2012. Accessed February 24, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46nfqd.

Coco, Gregory A. A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg the Aftermath of a Battle. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2017.

Creighton, Margaret S. The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s Forgotten History: Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War’s Defining Battle. New York, New York: Basic Books, 2005.

Kirby, Jack Temple. “The American Civil War: An Environmental View.” National Humanities Center, July 2001. Accessed March 27, 2022. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nattrans/ntuseland/essays/amcwar.htm.

Longnecker, Stephen. “Otelia’s Hoops: Gettysburg Dunkers and the Civil War,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 76, no. 1 (Winter 2009), 42-68. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.ycp.edu:8443/stable/27778872?Search=yes.

Mauldin, Erin Stewart. Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2018. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780190865177.001.0001/oso-9780190865177.

Meier, Kathryn Shively. Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Meier, Kathryn Shively. “Organic Armies: Military Engagement with Nature in the American Civil War.” South Central Review 33, no. 1 (Spring 2016), 37-52. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44016919?Search=yes.

Nelson, Megan Kate. Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46nhff.

Opresa, Ana-Lourdes, Juan-Alberto Gala, Luis Fernandez-Pozo, Jose Cabezas, and Francisco Soler. “Lead content in soils and native plants near an abandoned mine in a protected area of south-western Spain: an approach to determining the environmental risk to wildlife and livestock,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26, no. 29 (2019), 30386-30398. Accessed April 23, 2022. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.ycp.edu:8443/content/pdf/10.1007/s11356-019-06197-5.pdf.

[1] J. Howard Wert, “‘Twas Fifty Years Ago”, #13, Harrisburg Telegraph, quoted in Gregory A. Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg the Aftermath of a Battle (El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2017), 40.

[2] Lisa Brady, War upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 93.

[3] Brady, War Upon the Land, 95.

[4] The term “agroecosystem” describes a domesticated ecosystem developed for various agricultural activities and industries. For southern agroecosystems, Brady, War upon the Land: Military Strategy and the Transformation of Southern Landscapes (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 92-93.

[5] Lisa Brady, “The Wilderness of War: Nature and Strategy in the American Civil War,” Environmental History 10, no. 3 (2005): 436.

[6] Brady acknowledges that her choice to focus on Union operations in the South may to lessen the impact of southern voices on the same topics, no matter their race, gender, or status. Even as middle-to-upper class white southerners left documentation on the topic of the environment during the Civil War, they did not take part in the development of Union army strategies. Because of this, Brady leaves these southern voices sources largely unexplored. For limitations of sources, Brady, War upon the Land.

[7] Megan Kate Nelson, “Battle Logs: Ruined Forests,” chapter in Ruin Nation: Destruction and the American Civil War (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 104.

[8] Nelson, “Battle Logs” in Ruin Nation, 153-158.

[9] Erin Stewart Mauldin, Unredeemed Land: An Environmental History of Civil War and Emancipation in the Cotton South (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2018), 33.

[10] Mauldin, Unredeemed Land, 111-112.

[11] Mauldin, Unredeemed Land, 33.

[12] Mauldin, Unredeemed Land, 33.

[13] Kathryn Meier, Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 35-41.

[14] Robert L. Bloom, “”We Never Expected a Battle”: The Civilians at Gettysburg, 1863,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 55, no. 4 (Fall 1988): 182.

[15] Bloom, “We Never Expected a Battle”, 184.

[16] United States Surgeon-General’s Office, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-65) 2, part 1, National Library of Medicine Digital Collections. National Library of Medicine (Washington D.C.: NLM Publications and Productions, 1870) accessed March 28, 2022. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-14121350RX4-mvpart.

[17] Gregory A. Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg the Aftermath of a Battle (El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2017), 313-317.

[18] Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land, 313.

[19] Gordon Winslow, “The Wounded at Gettysburg.” Medical and Surgical Reporter (1858-1898) 10, iss. 14 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Aug 1, 1863. American Periodicals, accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/136431827/B4B0EB5D47D74A45PQ/3?accountid=29140.

[20] J. Howard Wert, “In the Hospitals of Gettysburg…,” #9, Harrisburg Telegraph, 1913, quoted in Gregory Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg The Aftermath of a Battle (El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2017), 315.

[21] Bloom, ”We Never Expected a Battle”, 184.

[22] Wert, “In the Hospitals of Gettysburg…,” in A Strange and Blighted Land, 315.

[23] Wert, “In the Hospitals of Gettysburg…,” in A Strange and Blighted Land, 315.

[24] Wert, “Twas Fifty Years Ago,” quoted in A Strange and Blighted Land, 41.

[25] John Blair Linn, The Diary of John Blair Linn, July 6-11, 1863. Journal. Centre County Library and Historical Museum, Bellefonte, PA, quotedin Coco, A Strange and Blighted land, 43.

[26] Linn, The Diary of John Blair Linn, quoted in A Strange and Blighted Land, 43.

[27] “OUR GETTYSBURG CORRESPONDENCE: The Last of the Dead Buried—Condition of the Wounded—The Battle-field and Relic Gatherers.” New York Times (1857-1922) (New York, New York), Jul. 15, 1863, American Periodicals, accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/docview/91768717?pq-origsite=summon.

[28] Meier, Nature’s Civil War, 35.

[29] Meier, Nature’s Civil War, 41.

[30] “A WEEK AMONG THE WOUNDED AT GETTYSBURG: II. Incidents, Sabbath Services in the Hospitals.” Christian Inquirer (1846-1864) 17, iss. 46 (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Aug 15, 1863. American Periodicals, accessed March 28, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/135707556/AEF19E4A2113412FPQ/1?accountid=29140.

[31] Winslow, “The Wounded at Gettysburg,” Aug 1, 1863.

[32] John S. Billings, “A FIELD HOSPITAL AT GETTYSBURG.: Establishing the Hospital. Preparing for Night. A Change of Location. The Removal. After the Battle.” The Youth’s Companion (1827-1929) 64, iss. 27 (Boston, Massachusetts), Jul. 2, 1891. American Periodicals, accessed March 29, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/127071823/AEF19E4A2113412FPQ/31?accountid=29140.

[33] William C. Way, letter by Way, chaplain of the 24th Michigan, August 7, 1863, Detroit Advertiser and Tribune (August 14, 1863) quoted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted land, 47.

[34] Jack Temple Kirby. “The American Civil War: An Environmental View.” National Humanities Center, July 2001, accessed March 28th, 2022, http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nattrans/ntuseland/essays/amcwarb.htm.

[35] Thomas W. Knox, “The Battle Field at Gettysburg. Scenes After the Battle. Visit to the Battle-Field,” New York Herald, article, July 9, 1863, quoted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted land, 47.

[36] Sallie M. Broadhead, The Diary of a Lady of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, from June 15 to July 15, 1863, quoted in Bloom, ”We Never Expected a Battle,” 181.

[37] Winslow, “The Wounded at Gettysburg,” Aug 1, 1863.

[38] United States Surgeon-General’s Office, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1870.

[39] Nellie Aughinbaugh, Personal Experiences, quoted in Bloom, “We Never Expected a Battle,” 182.

[40] Billings, “A FIELD HOSPITAL AT GETTYSBURG,” Jul. 2, 1891.

[41] Aughinbaugh, Personal Experiences, quoted in Bloom, ”We Never Expected a Battle,” 182.

[42] Bloom, “We Never Expected a Battle,” 182.

[43] Wert, “Twas Fifty Years Ago,” quoted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land, 40-41.

[44] Robert McClean, “A Boy in Gettysburg in 1863,” The Compiler, Jun. 30, 1909, quoted in Bloom, ”We Never Expected a Battle,” 182.

[45] Margaret S. Creighton, The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s forgotten History Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War’s Defining Battle (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2005), 148.

[46] The Compiler, 13, Jul. 20, 1863, Bayly, “A Woman’s Story,” quoted in Creighton, The Colors of Courage, 148.

[47] Creighton, The Colors of Courage, 133 & 152.

[48] Trowbridge, “Notes on the History of Adams County, Pennsylvania,” quoted in Bloom, ”We Never Expected a Battle,” 184.

[49] Stephen Longnecker, “Otelia’s Hoops: Gettysburg Dunkers and the Civil War,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 76, no. 1 (Winter 2009), 56.

[50] Longnecker, “Otelia’s Hoops,” 56.

[51] Longnecker, “Otelia’s Hoops,” 56.

[52] Longnecker, “Otelia’s Hoops,” 56.

[53] Brady, “The Wilderness of War,” 436.

[54] Nelson, Ruin Nation, 118.

[55] Early, “General J.A. Early’s Report,” Dec. 1882.

[56] Early, “General J.A. Early’s Report,” Dec. 1882.

[57] Early, “General J. A. Early’s Report,” Dec. 1882.

[58] Early, “General J.A. Early’s Report,” Dec. 1882.

[59] Wert, “Twas Fifty Years Ago,” quoted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land, 40-41.

[60] Longnecker, “Otelia’s Hoops,” 56.

[61] “OUR GETTYSBURG CORRESPONDENCE,” New York Times, Jul. 15, 1863.

[62] “OUR GETTYSBURG CORRESPONDENCE,” New York Times, Jul. 15, 1863.

[63] Henry V. Boynton, “A Visit to the Battleground,” letter, June 30, 1866, in The Christian Observer, vol. 11.Ed. James F. Clarke, Boston, Massachusetts, Sept. 18, 1913, quoted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted land, 43.

[64] Sophronia E. Bucklin, In Hospitals and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John E. Potter and Co., 1869), quoted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land, 24.

[65] Knox, “The Battlefield at Gettysburg,” quoted in A Strange and Blighted Land, 24.

[66] Knox, “The Battlefield at Gettysburg,” quoted in A Strange and Blighted Land, 24.

[67] J. Howard Wert, A Complete Hand-book of the Monuments and Indications and Guide to the Positions on the Gettysburg Battlefield (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: R.M. & Sturgeon Co., 1886), 109 excerpted in Coco, A Strange and Blighted land, 18-19.

[68] Coco, A Strange and Blighted Land, 18.

[69] Bucklin, In Hospital and Camp, quoted in A Strange and Blighted Land, 234.

[70] Maura Lyons, “An Embodied Landscape: Wounded Trees at Gettysburg,” American Art 26, no. 3 (Fall 2012): 46.

[71] C.J. Tyson, Battle-field of Gettysburg-Effect of Union Shot and Shell on the Trees on Culp’s Hill. 1868-1880. Stereograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-117889, accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97507634/.

[72] Mathew Brady, Wounded Trees at Gettysburg. 1863. Stereograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-steoe-2s02672, Civil War Photograph Collection, No. 2391. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011649197/.

[73] Battle-field of Gettysburg – Union breast works on Culp’s Hill, temporarily taken by the Rebels. 1868-1880. Stereograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-117888, Tipton & Myers’ stereoscopic views series, No. 537. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97507623/.

[74] Lisa Brady, “The Wilderness of War,” 440.

[75] “Section of Witness Tree recovered from Culp’s Hill, Gettysburg, 2011, with embedded Minié ball”. 2011. Photo. Gettysburg National Military Park, pictured in Maura Lyons. “An Embodied Landscape: Wounded Trees at Gettysburg.” American Art 26, no. 3 (Fall 2012), 62. Accessed April 3, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669222?pq-origsite=summon&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.