By: Hans Christian Clouser

Introduction

Gun violence in America has reached concerning new heights in the past decade. According to the Gun Violence Archive (2021), at least 13,000 Americans have died every year as a result of gun violence since 2014, with this number climbing to a staggering 19,000 in 2020. This issue is truly epidemic in nature in the United States. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic over the past two years has put seemingly controversial issues that dominated modern partisan politics, such as gun control, on the backburner. Of interest, this issue provides us with a bevy of policies and statistical points to examine.

The purpose of this research is to explore the relationship between causal factors of gun violence within states and the subsequent number of firearm-related deaths. States offer a distinctive and valuable point of comparison, due to the nature of American policymaking on this issue. States often use preemptive laws that limit the ability of local governments to regulate firearms (Pomeranz et al., 2021). Due to the polarized nature of this issue within the federal lawmaking body in the United States, there is rarely gun control legislation or guidance passed at the highest level of American government (Gun Law Scorecard, 2021). Combined, these two norms propel states into the position of primary policymaking on issues of control.

Understanding that states are the primary driver of policy means that cross-state collaboration could serve as a powerful deterrent to preventing gun-related death. Identifying specific factors under this umbrella and applying them to geographic regions will aid in recognizing important trends between states that are more likely to collaborate on policy solutions. Searching for statistical significance in a regional context will enable policymakers to target specific problems when considering solutions for preventing firearm deaths.

The thesis of this paper is that the potential causal factors, including guns per 1,000 individuals, percent gun owners in a population, population density, and gun law strength and width, will each have a disparate impact on the gun death rate in each of the five geographic regions in the United States identified in this analysis. In order to do this, rigorous quantitative analysis will be conducted. The paper first examines the discussion on causes of gun violence in the United States. This allows for the formation of common impactful factors, which become the independent variables that are identified in the data and methods portion. In the analysis and findings segment, the independent variables are tested and examined against the dependent variable, the gun death rate. Ultimately, understanding how firearms and gun policy are linked is vital to understanding the current debate in our country. It is quite literally a matter of life and death.

Contemporary Discussion on Gun Death and Its Causes

Contemporary literature on gun violence looks to examine this issue from a few different perspectives that are closely related to state gun restrictions and the effects they have on who can potentially own what types of firearms in a given state, as well as the effects gun ownership has on a population.

Gun laws and their relationship with firearms deaths are often explored using states as a primary lens of focus. Under this umbrella, one key idea is that state right-to-carry (RTC) laws have a direct effect on gun violence in states. Donohue (2018) examines the effects that RTC laws have on gun violence in every state within the United States. RTC laws are defined as “the right to carry concealed handguns when away from home without a permit or with a permit issued by a state to an applicant who meets requirements established by the state legislature” (Donohue, 2018, p. 67). These laws are considered to be less restrictive and are typically found in states considered to be politically conservative. Restrictiveness is often defined in the language of a state’s RTC laws, with “shall issue” being considered less restrictive than “may issue.” In their examination of the presence of RTC laws and crime, Donohue (2018) found a consistent positive relationship between the introduction of RTC laws and the incidence of both overall crime and violent crime. Further analysis found a statistically significant relationship between “shall issue” RTC laws and murder, robbery, assault, and burglary. In addition, states that have adopted RTC laws have seen increases in violent crime, ranging from 1.4 percent to 8.4 percent (Donoue, 2018).

In a study on state gun laws and homicide rates, funded by the United States Department of Justice, Siegel (2020) found similar results. Siegel found significant statistical evidence that permit and “may/shall issue” laws affected the homicide rate in the urban population of states. This statistically significant relationship is also discussed by Cook and Donohue (2017), who, throughout their work, provide explanations for why these factors are causally connected. Cook and Donohue (2017) note that there was a 42.3% drop off in violent crime, from 1977-2014, in states that did not adopt RTC policies. Comparatively, states that did adopt RTC laws saw only a 4.3% decrease over that same time period. Cook and Donohue further theorize that, while proponents of gun rights believe carrying firearms serves as a constant form of deterrence and protection, it is also true that firearms are much more likely to be involved in incidents of escalation, such as public confrontations caused by some form of intoxication or anger, than they are to be involved in incidents of self-defense. In addition, the authors discussed how more guns in public locations can have tertiary effects, such as the projected 100,000 stolen guns per year.

In addition to the RTC laws discussed above, Cook and Donohue (2017) also target sentencing add-ons and preventative policies as historical examples that have proven to be effective in mitigating gun violence. Studying the effects of the Lautenberg Amendment of 1996, which banned people who had been convicted of a misdemeanor as a result of domestic assault from possessing a firearm, the authors noted that its gradual integration served as an excellent case study on its effectiveness. For example, gun murders of female partners were reduced by 17% during this time period (Cook & Donohue, 2017). This policy serves as both a deterrent to those that might otherwise commit domestic assault and also as a preventative measure, as that group of individuals is no longer qualified to purchase a firearm.

This concern over the illegal acquisition of guns closely aligns with the second perspective on gun control in this discourse community. Kahane presents this perspective in a 2020 study of state gun laws and the movement of crime guns (guns that are used to commit crimes) between states. The most significant of these was the fact that crime guns are often bought in states with more lenient policies and smuggled into more restrictive states, where the crime then occurs. Kahane (2020) defines lenient as a combination of less restrictive gun purchasing and gun tracking policies. As a result, if a restrictive state is surrounded by more lenient states, it has the potential to be affected by the lenient policies of its neighboring states. In addition, the study examined both the top and bottom ten states, in terms of crime gun exports, from 2010-2015. These findings saw states that fit into her categorization of lenient states, such as West Virginia and Mississippi, consistently seeing more crime guns smuggled out of their states, while more restrictive states, such as Maryland and Illinois, were often recipients of the illegally imported crime guns. This connection indicates that lenient state policies do affect gun-related crimes, even if it occurs in neighboring states, due to the enabling nature of their policies.

A state-based approach is common in modern examinations of American gun control policy. Pomeranz, Silver, and Lieff (2021) provide a rigorous case study on why these state policies, for better or worse, are extremely hard to change. The authors of this study examined every state’s firearm legislation from 2009 through 2018, with the goal of exploring the relationship between preemptive laws, actual legislation regarding the issue, and lack of legislation on the issue. Preemptive legislation is defined as laws passed by states that define what action, if any, local government can take on a particular policy matter. Research indicates that there are three categories of states, based on the comparative relationship discussed above.

The first of these categories are states that have limited preemptive laws but a significant amount of gun control legislation. States in this category typically favor gun control over gun rights and allow their local municipalities to implement firearm policy tailored to the needs of their population. One potential benefit exclusive to this state-level position on gun control is the potential for particularly impactful local ordinances to be adopted at the state level.

The second category presented included states that have both significant gun control legislation and restrictive preemptive laws. These states may be seeking statewide consistency when it comes to firearm policy. However, even states with the greatest number of laws enacted in this category have a greater number of preemptive laws that have not been followed by legislation on the issue, indicating that there is limited opportunity for local policymakers to introduce community-specific laws on the matter.

The final and most restrictive (in terms of local government’s ability to produce policy) of the categories are states that have passed a significant number of preemptive laws, but little to no actual gun control policy. This faction, which represents more than half of the states across the country, is actively pro-gun rights, as a large portion of the legislation they pass is to restrict local government’s ability to implement legislation on the issue, rather than passing laws directly affecting gun rights. The study concludes that large-scale change to gun control policy is not likely, due to the predominance of the third group of states and the engrained nature of their preemptive laws.

Smith and Spiegler (2017) further examine this phenomenon on a state-by-state basis. Within their research, the authors explore the relationship between gun control laws and gun-related deaths. Gun control laws are defined as “restricting access to guns for those most likely to use them for violent ends” and “specifying what types of guns are permitted and how large ammunition magazines are allowed to be” (p. 236). The study discovers a statistically significant negative relationship between the two variables, indicating that stronger gun control policy can be directly tied to the prevention of gun-related deaths. Smith and Spiegler (2017) also explore the relationship between access to mental health services and gun deaths but were unable to prove that the relationship was statistically significant, demonstrating that other gun laws were more prominent in indicating the amount of firearm-related death than access to mental health services.

Another point of interest in the contemporary academic literature surrounding gun laws and firearm crime is presented from a broader perspective that, unlike the previous literature discussed above, is not directly tied to states. Sherman (2020) presents evidence that the number of households that own a gun is directly related to gun crime, death, and injury. More specifically, there is a positive relationship between the percentage of households in any given territory that possesses one or more firearms and higher rates of gun deaths in crime. This is significant, as nearly 50% of Americans live in a gun-owning household. The higher the percentage of these households in close proximity to each other (such as in an urban area), the greater the chance that gun violence will occur.

There is certainly a variety of statistics, laws, and research involving the state of gun control within the United States. Based on this collection of resources, there are a few general conclusions that seem to be universally accepted. First, it is apparent that gun control legislation has an effect on the amount of gun death that any given state experiences. Secondly, it is also clear that the larger concentration of firearms in an area, the higher the chance that there will be violence and, likely, death. This is a theory that has been supported by statistical analysis, whether it involved RTC laws or the proximity of households with firearms.

However, under the umbrella of these conclusions is a diverse set of theories (which are far from mutually exclusive) on gun control and its effects. RTC laws have been found to be especially impactful in determining how much gun-related death states may experience. However, it is also clear that background checks have a role to play. Mental health is touted as a reason behind gun violence, but that relationship has yet to be fully explored or proven. Gun policies and death rates are also certain to be influenced by preexisting conditions. The two most prominent examples from the literature are preeminent legislation and cross-state gun crime. Preeminent legislation slows or halts potential local-level gun control, indicating that nearly all firearm policy in the United States comes from the state level. A potential outcome of this system is the use of guns acquired in a state with a more gun-rights-focused approach to commit crimes in neighboring states with stricter gun laws.

There is no catch-all metric for examining gun control. However, by using central ideas from the contemporary discourse on the topic, one can thoroughly look at gun control and gun deaths inside of states in a comparative manner. Examining the volume, type, and effectiveness of legislation is vital to this endeavor. In addition, considering factors such as the presence and scope of preeminent legislation, as well as considering the attitudes and policies of neighboring states, are also important. Using this combination of factors, one could examine the gun death rate in geographical regions in a rigorous, effective, and comparative manner.

Examination of these sources indicates each is relevant to the research question proposed by this paper: “What factors contribute to the gun death rate at the regional level?” The hypothesis for this paper is founded on the nature of this relationship: the potential causal factors discussed below have an impact on the gun death rate of the five geographic regions in the United States identified in this analysis. Within this model, the factors discussed serve as the independent variables, while the gun death rate represents the dependent variable. For the purpose of aligning the level of analysis, the gun death rate will be explored through examining these deaths on a per-100,000 people level, so that population differences are normalized between the different regions.

Each of the independent variables has a unique interaction with the dependent variable when using a formulaic approach. The first factor, the number of firearm owners per 1,000 in each state of a region, projects to have a positive relationship with the gun death rate per 100,000. The greater number of guns, the higher the gun death rate. Similarly, the variable that examines the percentage of the population that owns a firearm would theoretically result in a higher gun death rate per 100,000. The final factor that is predicted to have a positive relationship with the gun death rate is population density. This relationship implies that the greater the population density, the higher the gun death rate per 100,000. The two remaining variables are projected to have negative relationships with the dependent variable. The first of these is gun law width. As gun law width increases, it is logical to forecast that the gun death rate will decrease. Gun law scorecard shares a similar relationship: stronger gun laws are likely to correlate with lower gun death rates.

Data and Methods

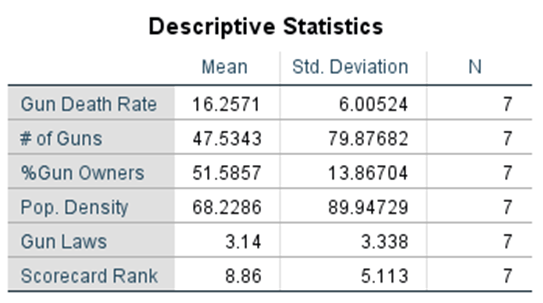

The statistical testing of this hypothesis will use seven variables. These variables will be controlled on a regional level.

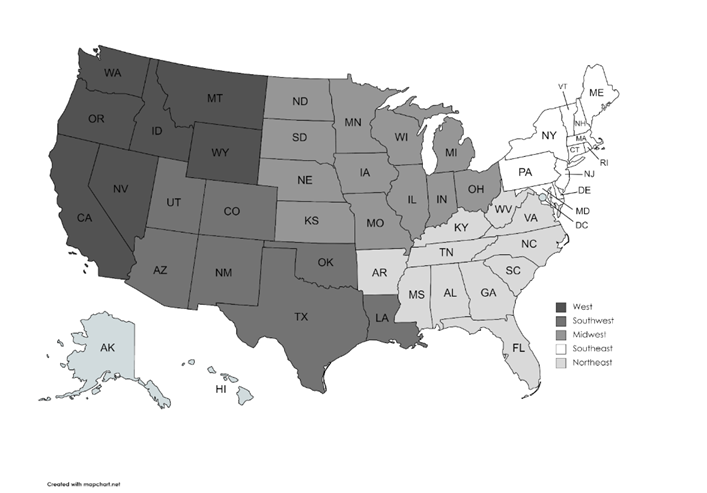

The first of these variables is the regions themselves. There are five regions of the United States represented in this paper: Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Southwest, and West. This is how the states were separated into regions:

- Northeast Region: Maryland, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maine, and Vermont.

- Southeast Region: Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

- Midwest Region: North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan.

- Southwest Region: Louisiana, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Utah, and Colorado.

- Western Region: California, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming.

Hawai’i and Alaska were not included in this or any of the subsequent variables. In this variable, the unit of analysis is states. This variable is designed to combine individual states into regions. Each region is represented by a number that serves as a placeholder for the name of a region: Northeast=1, Southeast=2, Midwest=3, Southwest=4, and West=5.

Regional Breakdown of the United States

The gun law width variable was developed by the author of this paper to examine the variety of gun laws in states. States were assessed on nine categories of firearm legislation: strong domestic violence restrictions, mandatory universal background checks, required registration of all firearms, obligatory permit when purchasing a firearm, open carry regulations, safe storage/child access laws, magazine capacity stipulations, and assault weapon restrictions. Each state received a 1 for each category it had legislation in and a 0 for each category it did not. As a result, the highest possible score would be a 9, and the lowest possible score a 0. The determination of whether a legislation type was present was made using each state’s gun law breakdown on Gun Law Scorecard (2021), a website that is part of Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, and World Population Review’s (2022) gun laws by state data.

An additional variable used is the gun law scorecard. This variable provides a letter grade for each state based on the strength of its gun laws and was created and updated using data from Gun Law Scorecard (2021). In order to convert letter grades into statistical data, each letter was assigned a corresponding number. The highest a state can obtain is a 1, or an A+, and the lowest a state can obtain is a 14, which is an F. It is important to note that no state obtained an A+ (1) or an F+ (13). States with smaller numbers, therefore, have a higher score on the Gun Law Scorecard in this dataset.

Another independent variable used in this analysis is the number of registered guns per 1,000 people by state. In this variable, the units of analysis are the firearms themselves. The number of guns was retrieved from World Population Review’s (2022) guns per capita dataset, and the rate of firearms per 1,000 people was determined. It is of note that this variable is representative of only registered firearms, not total firearms.

Percentage of population that owns a firearm uses data produced by World Population Review (Gun Ownership by State, 2022). The variable measures the percentage of the population in a state that owns at least one firearm. The percentages in this test are represented as numbers, rather than percentages. For example, 55.5% would be entered as 55.5.

Population density is the next independent variable that will be used in this model and is defined as the number of individuals per square mile. The data for this variable was extracted from the United States Census Bureau (2022).

The final variable to be used in the statistical analysis is the firearm deaths per 100,000 people. A firearm-related death, within the confines of this paper, is defined as an incident of homicide, murder, suicide, or any other incident where the discharge of a firearm resulted in the death of one or more individuals. The variable was created using the most recent data available from the Gun Violence Archive (2021) and represents the firearm deaths per 100,000 in each state in 2021.

All measures of the significance will be made at the 90% confidence level, where p=.10. While most tests usually use a .05, or 95% confidence interval, the regions of this paper, denoted by “n”, are not large enough to reach this threshold. Breaking the states into five regions dilutes the sample size, meaning that accepting a higher chance of committing type one error is necessary in order to better understand the relationship between the variables. Type one error occurs when research suggests there is a relationship between variables when a relationship does not exist.

It is also important to note that the tests being conducted are regional in nature. As a result, they are not specific to individual states or on a national level. Additional research could be conducted in the future applying these same variables without controlling for region in order to draw a more broad, national level-conclusion. In the opposite way, a more specific and detailed study could apply the same variables to each individual county within a state, allowing for conclusions to be made at the individual state level.

Quantitative Analysis and Findings

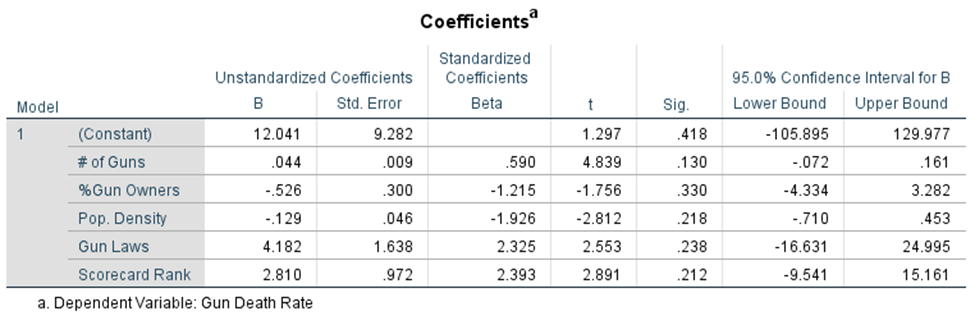

The analysis in this portion of the paper was conducted using five individual tests. The results of these tests were of note when it came to the hypothesis that the potential causal factors have an impact on the gun death rate of the five geographic regions in the United States identified in this analysis. In three regions, the correlation of these factors was found to be statistically significant. However, in the two other regions, they were not. In none of the five regions were all five independent variables found to be statistically significant. As a result, there is no overarching relationship between these factors and the gun death rate per 100,000 in all five regions.

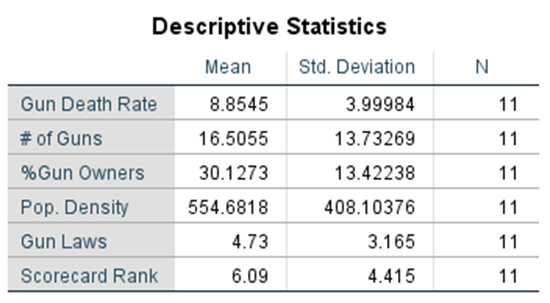

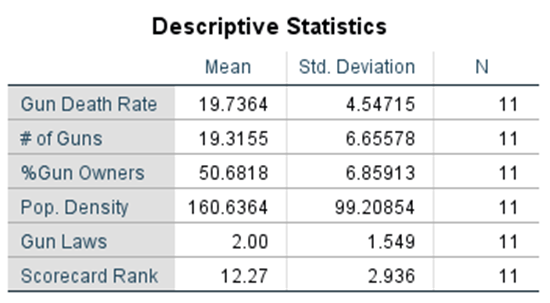

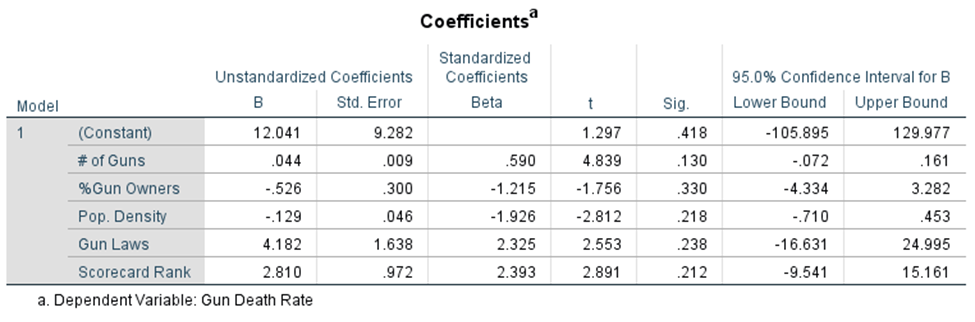

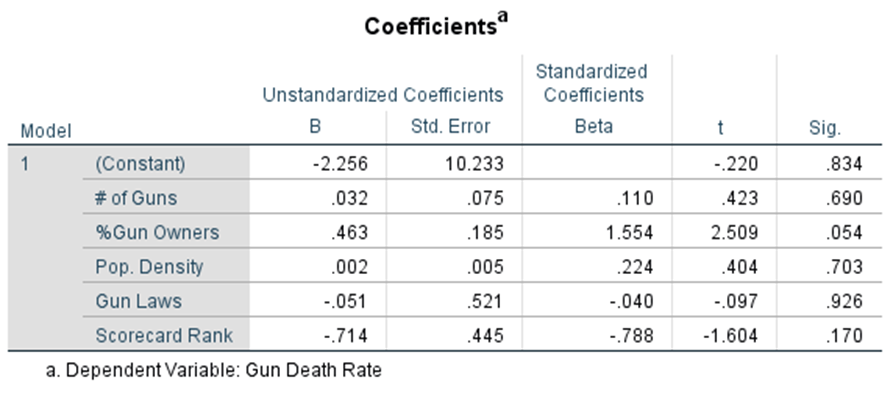

Region 1 (Northeast)

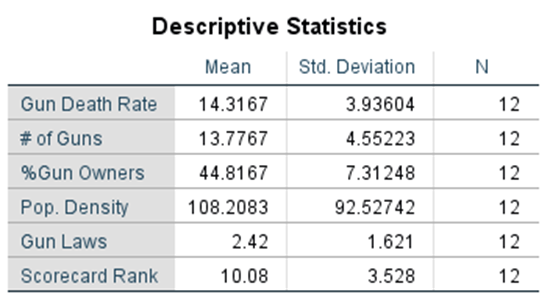

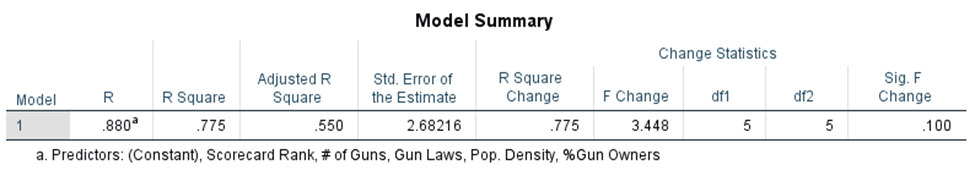

The analysis for the first test was conducted using a multi-variant linear regression model while controlling for region one, the Northeastern United States, and involved eleven states. The analysis finds the overall relationship to be statistically significant. The strength of r-squared, at .775, indicates that this is a safe claim, as this number is well over the .3 value which is indicative of a strong relationship.

Examining the individual factors is essential to understanding why this relationship exists. Of the five factors, the percentage of gun owners in a state is the only variable that is under the 10% threshold, indicating that it is the most impactful factor in the region with a p-value of .054. As the percentage of gun owners rises, so does the gun death rate per 100,000, making this outcome positive in nature.

Outside of this, a variable that was relatively close to achieving statistical significance was the gun law scorecard rank. This variable was 7% over the threshold established in the previous portion of this study as statistically significant, with a 17% chance of committing type one error. The mean for the scorecard was the lowest of the five regions, with an average of just over 6, a B- on the scorecard, indicating the overall strength of gun control in the region. However, similar to the percent of the population that owns a firearm, there is a notably large standard deviation, at over three grade changes, meaning there is a wide variety of scorecard grades.

None of the three remaining variables (registered guns per 1,000, population density, and gun law width) achieved statistical significance. While the population density average (554 people per square mile) and its standard deviation (408.1) were both easily the highest of the regions, it was not found to be significant. This is likely due to the vast differences in the region making it hard to overcome potential error with a sample size as small as eleven states. The average and standard deviation of guns per 1,000 individuals were not of particular note: they were not statistically significant and were not outliers from the other four regions. The Northeast region also measured the highest gun width average (4.73) and standard deviation (3.17).

Exploring the statistical findings in a substantive way further develops the understanding of the relationships in the Northeast region. Percent of the population that is gun owners was the variable found to be statistically significant in this region. The relatively high regional variance, coupled with a low mean, demonstrates why the percentage of the population that owns a firearm in states in this region is the main predictor of gun-related death. In other words, there were likely outlier states, in terms of percentage of gun owners, and they experienced significantly higher amounts of gun-related death when compared to states with lower percentages of gun ownership. In a region where laws tend to be more restrictive, the armament of a larger portion of the population logically rises in importance and impact on the gun death rate. The implication is something that policymakers should consider when evaluating the potential for successful cross-state collaboration on the issue.

While no factors outside of the percentage of gun owners were found to be statistically significant, the relationship as a whole still meets the criteria. It is important to logically connect the percentage of gun owners to both the gun law scorecard and gun law width. While those variables were not found to be significant on the gun death rate, one can imagine that the strength of each of these, or lack thereof, would inform on the percentage of gun owners in any given state in any region. This potential connection is an important point to keep in mind when viewing each region’s results.

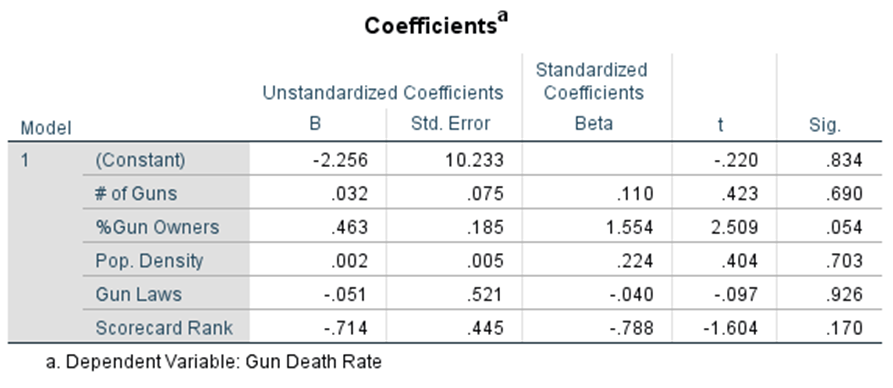

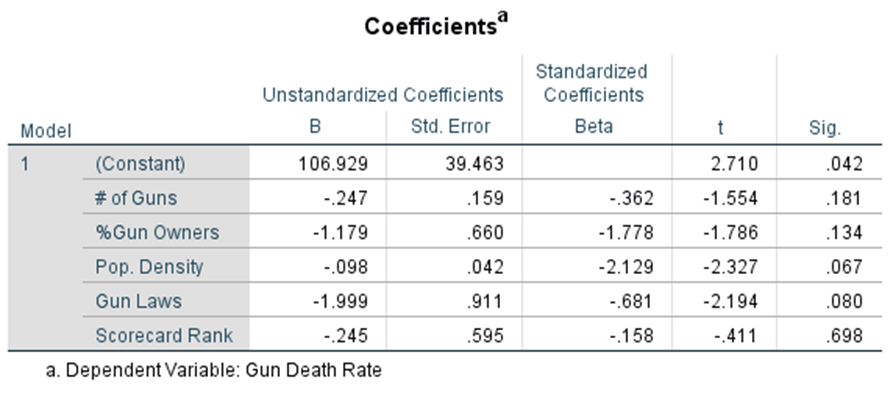

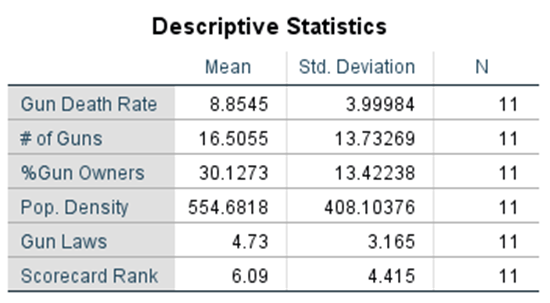

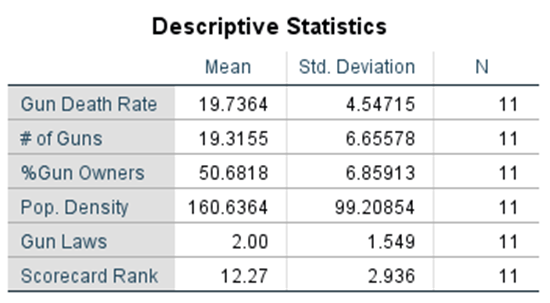

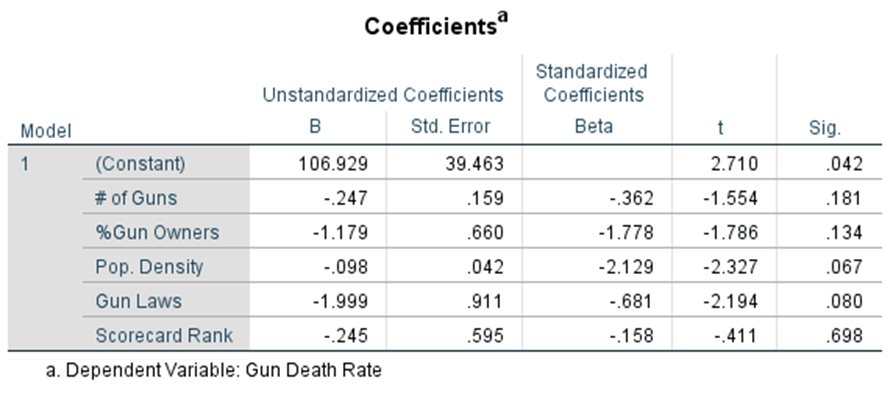

Region 2 (Southeast)

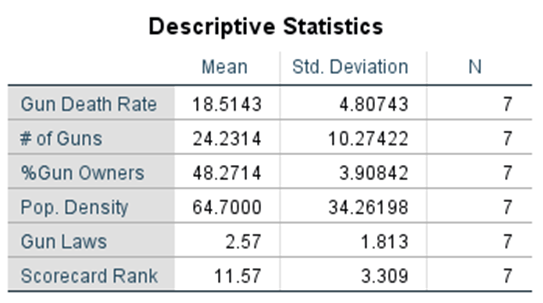

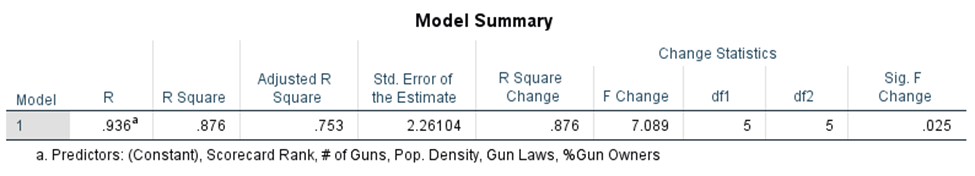

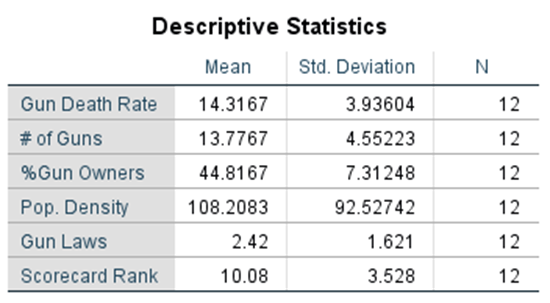

The Southeast region also contained eleven states. Similar to region one, this region was tested using a multi-variant linear regression model. The model as a whole had a 97.5% chance of claiming a relationship without committing error, well above the 90% standard. The r-squared value (.876) further underscores the strong nature of this relationship, indicating that this region meets the criteria established for statistical significance.

Two of the five independent variables were found to be statistically significant. The first of these was population density, with a 93.7% chance of having a relationship with gun-related deaths per 100,000. Considered within the context of the regions, this can be better understood. Outside of region one, the Southeast has the highest population density at nearly 160.63 people per square mile, without having a notable amount of standard deviation when compared to other regions. However, interestingly, population density has a very slight negative relationship with the gun death rate: as the population density increases by a person per square mile, the gun death rate decreases by .098 persons per 100,000. This is the inverse of what the literature and variable definition above asserted, where increased population density was predicted to result in increased gun-related death. Notably, this is one of three regions, along with the Midwest and West, where this relationship is negative, but the Southeast is the only region where this variable is statistically significant.

By scrutinizing the population density, it is possible to conclude that this variable was affected by the large population density and lack of anomalous standard deviation to match that. Given this large population density, rural pockets likely are less monitored by law enforcement. That, coupled with the cultural importance of firearms in this region, and the lack of gun laws of significant variety or substance, explains why population density is significant in a direction contrary to predicted norms. While firearms are a way of life for many residents of the Southeast region, restricting the type of firearms available to purchase and own, and who has access to them, has proven to be a valuable tool in lowering the gun death rate in the region.

The second variable of statistical significance in the Southeast is the gun law width variable, with a p-value of .08. Given the regional context, this is logical. The Southeast has the lowest mean score, at 2, while also having the lowest standard deviation for this variable at 1.55. In essence, the majority of states in the region do not have strong gun law width. As a result, any state with a higher score in this rating will experience a statistically significant decrease in gun-related deaths in this area.

Each of the three remaining variables was not statistically significant. The percentage of gun owners came closest, with an 86.4% chance of a relationship existing. Despite over 50% of the population owning a firearm, the lack of real standard deviation (close to 6.86%, the lowest of all regions) prevented any potential relational patterns from cementing themselves. The number of registered guns per 1,000 people, as well as the graded scorecard, were not significant within the region and did not display distinct outlier means or standard deviations when compared to their counterparts in other regions.

Looking at the meaning behind the statistically significant variables can further inform a better understanding of regional trends.

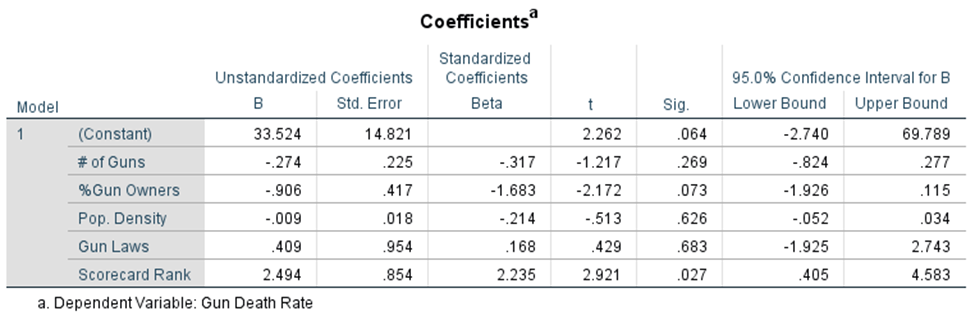

Region 3 (Midwest)

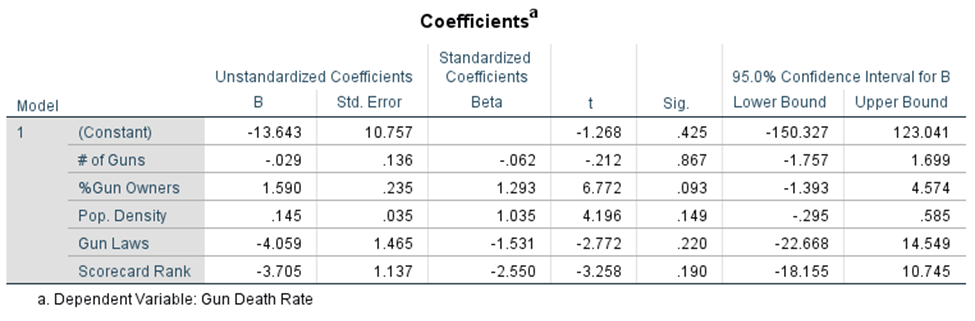

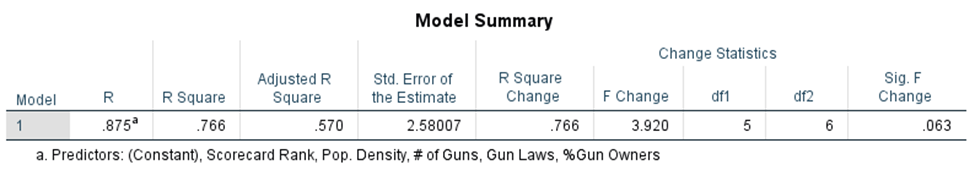

The Midwest model was found to be statistically significant by the author of this study with an overall p-value of .063. R-squared again promoted the strength of this relationship with a .766 value.

In parallel with the Southeast region, the Midwest region analysis resulted in two statistically significant independent variables. The percentage of gun owners was one of these variables, with a p-value of .073. The region’s mean percentage of gun owners in a state was 44.81%, second lowest among the regions, while its standard deviation of 7.31% was third out of the five regions. Curiously, this statistically significant variable is another that runs against the consensus of literature and the forecasted interaction of this factor with the dependent variable: in region three, as the percentage of gun owners increases, the number of firearm deaths per 100,000 decreases. This is the inverse of the positive relationship between the same variables in region one, indicating that the same factors may in fact impact outcomes in different ways on a region-by-region basis. This variable has a positive relationship in two regions (both of which are significant) and a negative in three regions (one of which is significant), indicating that it varies in direction and significance in each region, despite the prediction of a consistent directional relationship.

Gun Law Scorecard was the second statistically significant variable for the Midwest, with p=.027. The Midwest region’s average score was 10.08 (a D+ on the scorecard), with the second-highest standard deviation among the regions at over 3.5 grade increments. As the number representing the score increases, the amount of firearm death also increases.

The remaining three variables were statistically insignificant. None of these three were remotely close to the 10% type one error target. The mean and standard deviation of the gun law width and population density variables did not present anything intriguing enough to challenge the notion that they are not significant when compared to cross-regional norms. While the Midwest had the lowest average number of registered guns per 1,000 at 13.78, it also had the lowest standard deviation for that same variable (4.55), showing that the states within the region did not demonstrate enough variance for the statistical model to claim a relationship.

The region’s significant variables can again be explored by examining known regional characteristics. Within the scope of this region, the significance of the gun law scorecard variable is clear: in a region with relatively weak gun laws, a large standard deviation would indicate a few outlier states with better than average scores that drive up the standard deviation while also experiencing a low enough death rate to cause the variable to be statistically significant. The significance of the percentage of gun owners relationship may be explained by the lack of a variety of strong gun laws in the region. Given these characteristics, it is possible that states with a larger percentage of gun owners actually experience deterrence as a result of this. In a state where it is more likely than not that someone has a gun, an individual may be less likely to participate in gun violence, which is a key factor in the gun death rate. Coupled with the gun law scorecard variable, it is possible that some states in the Midwest region effectively provide firearms only to those who will safely own and use them. Decision makers for neighboring states in this region would benefit from attempting to replicate this success.

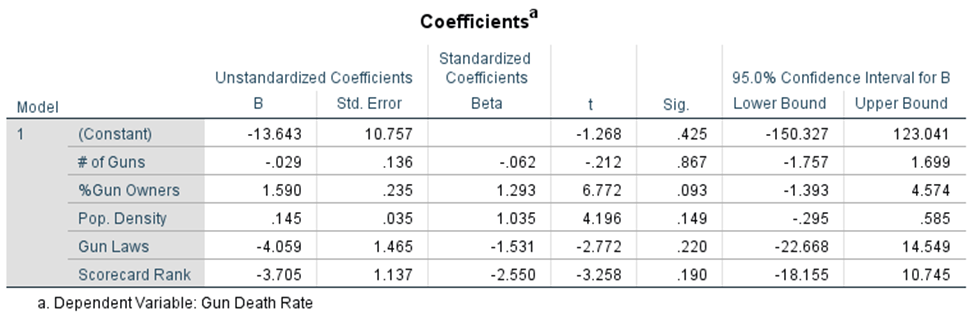

Region 4 (Southwest)

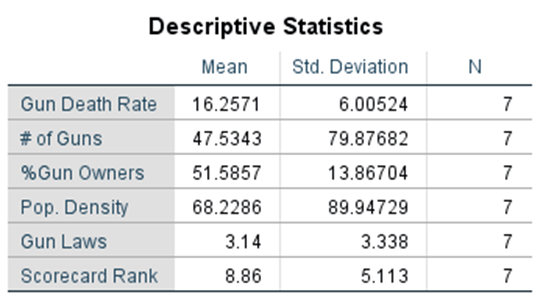

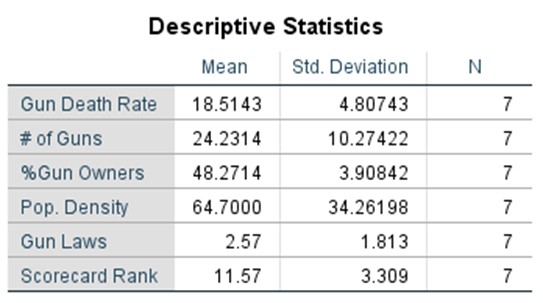

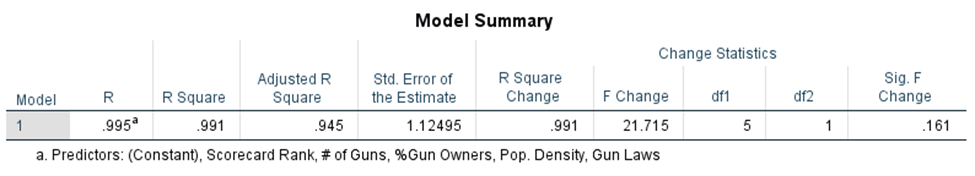

The fourth region, the Southwest, was the first region where the overall model did not meet the p=.1 barometer for statistical significance, with a 16.1% chance of type one error if claiming a relationship was present.

Despite these results, one of the independent variables was itself significant in relation to the gun death rate per 100,000 for region four. The percent of gun owners was significant at the .093 level. Region four had the third highest average for this variable, with a mean of 48.27%. This number is within three percentage points of the highest mean in the regions. More notably, the standard deviation for the percentage of gun owners was by far the lowest of the five regions used in this case study. The Southwest’s standard deviation was less than 3.91%, while each of the other regions had over 6.5% for their standard deviations. As this percentage increases, the gun death rate also increases, making this relationship positive in nature.

Population density was the next variable closest to the 10% threshold, with a 14.9% chance of type one error if claiming the existence of a relationship. Region four has the lowest mean population density, with 64.7 individuals per square mile. The Southwest also has the lowest standard deviation among the five regions in this category, with a change of 34.26 persons per deviation. Ultimately, this consistent lack of density and uniformity is likely what prevented this factor from achieving statistical significance, given the relatively small amount of change and the low n value.

The remaining three variables were more than seven percent removed from the established p=.1 standard and did not approach statistical significance. Neither the gun law width nor the scorecard rank presented means or standard deviations dissimilar enough to other regions’ scores in these categories to be of note. The average number of guns per 1,000 was the highest of regions one through four, at 24 per 1,000, and its standard deviation of close to 10.27 was the second highest. While these numbers are interesting, no claim of relationship can be made, as this variable was the least statistically significant in the Southwest.

The Southwest’s substantive outcomes are relatively unsophisticated in nature. Given the uniform amount of low population density, it is clear that there was not enough state-to-state variance to establish a relationship. The statistical significance of the percentage of the population that owned at least one firearm is also straightforward. States with higher ownership rates experienced a higher gun death rate, due to an increase in the percentage of the armed population. In this region, higher amounts of gun-owning individuals will result in more gun deaths. To combat this, finding a way to decrease the percentage of gun owners, whether that be through restrictions or incentives, will be necessary to curtail future violence.

Region 5 (West)

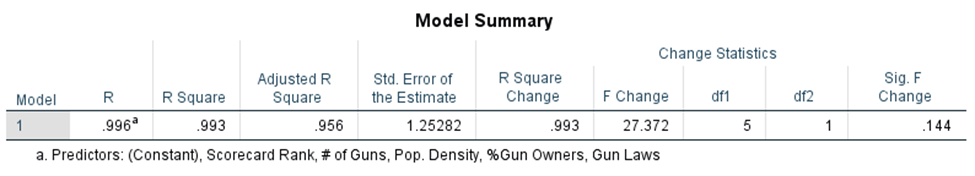

The Western region was found to be statistically insignificant, with a value of p=.144 for the relationship as a whole.

Within this region, none of the singular independent variables achieved statistical significance. The small group size of seven states, as well as the outlier status of certain states within this regional operating environment, certainly contributed to this result. The closest variable to meeting the p=.1 requirement was the number of registered guns per 1,000. When examining this factor, the mean number of guns per 1,000, 47.54 was nearly double the number of any other region. This was coupled with a standard deviation of 79.88, which was almost eight times larger than the second largest standard deviation. The reason for this is twofold: Wyoming has 228.1 guns per 1,000 residents, which is nearly five times the rate of any other state in this study. Secondly, both California and Washington are in the bottom twelve states in this same measurement, with California having 8.69 guns per 1,000 and Washington clocking in with 11.64 guns per 1,000. In essence, this region has outliers in both extremes, resulting in both a large average and standard deviation when compared to any of the other four regions’ rates with this variable. This extreme variance is hard to overcome given the sample size.

Region five also had the largest mean of the population that owned a firearm, with 51.59% owning one. The standard deviation of 13.87% was similar to region one’s 13.42%. Both of these numbers are much higher than the other regions, indicating the variance in this regard in the Western region. This can again be explained by the low n number and the clash between California and Washington (28.3% and 42.10%-gun ownership respectively) against Wyoming and Idaho (66.2% and 60.1%-gun ownership rates).

Population density, gun law width, and gun law scorecard rank each experienced similar levels of this variance, as each variable experienced the highest amount of standard deviation among its peers in other regions, likely as a result of the contrasting relationship between Washington and California against Wyoming and Idaho. Essentially, California and Washington represent extreme lows in gun ownership rates and the number of guns per 1,000 people. Meanwhile, Idaho and Wyoming are both composed of immensely dispersed populations, where a high percentage owns an outlier number of firearms. Given the size of the region, overcoming these extremes makes proving a relationship between states in this region a challenge.

These extreme differences, between four states out of the seven in this geographic region, do not bode well for potential region-wide collaboration on the prevention of firearm-related deaths. Policymakers in this region will likely need to focus on individual states within the region to combat gun death, as the ideological and demographic differences that exist between some states in this region are likely incompatible for joint solutions.

Conclusions

The findings in the analysis do not fully support the hypothesis that all five regions would be affected by the independent variables formulated above. However, the region-by-region variance displayed in the testing could be a useful tool for policymakers at all levels. Understanding which of the independent variables has the greatest effect on the gun death rate for any region, or the causes behind an apparent lack of impact, can be useful in both intra-state and inter-state communication on the issues surrounding gun control.

The variables that were found to be of statistical significance were directly related to the literature on the topic. Sherman’s assertion (2020) that a higher percentage of gun-owning households in close proximity to one another would relate to higher gun violence can be directly related to the positive, statistically significant, relationship between the percentage of gun owners in a population and gun death rate in both the Northeast and Southwest. In addition, the significance of gun law width in the Southeast, and the gun law scorecard rank in the Midwest are both reflective of numerous relationships posed by the literature. The increased access to firearms, as a result of a lack of gun law variety or strength, and the underlying relationship with gun violence was underscored by Siegel’s study (2020). Furthermore, the gun law scorecard’s significance on a regional level is indicative of Kahane’s 2020 findings that examining state gun laws on their own does not account for the laws of other states in the area, whose gun law strength or weakness affects the states around them. The connection between these variables can also be understood through the 2021 Pomeranz et al. study of preemptive laws. More specifically, the Southeast’s gun death rate’s tie with the statistical significance of the gun law width variable can be explained by the consistent presence of preemptive laws, coupled with a lack of state-level policy, which is demonstrated in both the index breakdown and total of gun law width for many states in the region.

However, two of the variables found to be statistically significant displayed behavior that was inconsistent with, or opposite to, both the literature and the nature prescribed to the variables by the author of this paper. Population density was found to be statistically significant in region two but demonstrated a relationship that was negative in nature: as the population density increased, the gun death rate decreased in the Southeast. This runs contrary to the view that an increase of gun-owning population density will result in higher amounts of gun violence (Sherman, 2020). The percentage of the population that owns at least one firearm was found to be significant in the Midwest, despite the fact it also held a negative relationship with the gun death rate. This is contrary to the two other regions where this variable was statistically significant, where the relationship was positive.

A regional study of firearms is one that is rarely taken when using statistical analysis. By splitting the 48 mainland states into regions, one is able to take a more specific approach than testing individual states, while still maintaining the comparative nature of the exercise. Despite limitations coming from the sample size, this research demonstrates the value of a regional analysis of firearms. Regional testing allows for a narrowed focus that is both relevant and important to decision makers in each region, as sharing the geographic proximity established through regions makes working together on this issue much easier and more likely. In the long run, politicians and public servants can use these findings to identify which aspects of gun control are most relevant to their region and strive to further cross-state cooperation with neighbors, with more specific goals than they would have had to work with before the completion of a regional analysis.

Future studies may look to increase the sample size in a few ways. One such way would be to maintain the geographic regions prescribed but break each state into congressional districts and collect data at the district level. Future research may also look to apply these common factors to individual states, using counties as the unit of analysis from which to gather and integrate data. While that is a time-consuming and challenging endeavor, narrowing a study to the county level would exponentially increase the sample size and allow policymakers to draw succinct conclusions on the relationship between the gun death rate and its potential causal factors within their state.

Ultimately, there seems to be a notable agreement within the current discourse community surrounding state gun policy: more lenient gun policy ultimately results in more violent crime and death. It should not come as a surprise then that the statistical evidence presented in this paper generally supports that theory and certain regional patterns that run along these lines. Working with geographically similar states will be essential to creating change and furthering research on this issue as it remains at the center of American partisan politics. Whether one agrees with gun control or not, there is significant statistical evidence to support the fact that common sense gun control is effective at saving a large number of lives. Saving lives is something that is hard to argue against.

References

Cook, P. J., & Donohue, J. (2017). Saving Lives by Regulating Guns: Evidence for Policy. Science, 358(6368), 1259–1261. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar3067.

Donohue, J. (2018). More Gun Carrying, More Violent Crime. Econ Journal Watch, 15(1), 67. Retrieved from https://web-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.ycp.edu:8443/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=de767feb-ed93-4544-99b2-59801ef465e6%40sessionmgr101&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=128779276&db=bth.

Gun Laws by State. (2022). Gun Laws by State 2022. World Population Review. Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/gun-laws-by-state.

Gun Law Scorecard. (2021). Annual Gun Law Scorecard. Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. Retrieved from https://giffords.org/lawcenter/resources/scorecard/.

Gun Ownership by State. (2022). Gun Ownership by State 2022. World Population Review. Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/gun-ownership-by-state.

Guns Per Capita. (2022). Guns Per Capita 2022. World Population Review. Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/guns-per-capita.

Gun Violence Archive. (2021). Past Summary Legers. Gun Violence Archive. Retrieved from https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/past-tolls.

Kahane, L. (2020). State Gun Laws and the Movement of Crime Guns Between States. International Review of Law and Economics, 61, 105871. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2019.105871.

National Rifle Association of America, Institute for Legislative Action. (No Date). Right-to-Carry. National Rifle Association of America, Institute for Legislative Action. Retrieved from https://www.nraila.org/get-the-facts/right-to-carry-and-concealed-carry/#:~:text=Right%2Dto%2DCarry%20(RTC)%20laws%20recognize%20the%20right,established%20by%20the%20state%20legislature.

Pomeranz, J. L., Silver, D., & Lieff, S. A. (2021). State Gun-Control, Gun-Rights, and Preemptive Firearm-Related Laws Across 50 US States for 2009–2018. American Journal of Public Health, 111(7), 1273–1280. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306287.

Sherman, L. (2020). Shattering the Paradox of Guns and Crime: Incidence, Prevalence, and the 2020 Stockholm prize. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(4), 1355-1357. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12522

Siegel, M. (2020). The Impact of State-Level Firearms Laws on Homicide Rates by Race/Ethnicity. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/254669.pdf.

Smith, J & Spiegler, J. (2017). Explaining Gun Deaths: Gun Control, Mental Illness, and Policymaking in the American States. Policy Studies Journal, 48(1), 235-256. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12242.

United States Census Bureau. (2021). Historical Population Density Data (1910-2020). U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/density-data-text.html.

ANNEX A

Region One:

Region Two:

Region Three:

Region Four:

Region Five:

ANNEX B

Index of State Breakdown by Gun Law Type

| State | Strong Domestic Violence Restriction | Universal Background Check | Required Registration of all Firearms | Permit Required to Carry Firearm | Permit Required to Purchase Firearm | Restrictions on Open Carry | Safe Storage Laws/ Child Access | Restriction on Magazine Capacity | Assault Weapons Restrictions | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| CO | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| CT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| DE | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| FL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| GA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| ID | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IL | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| IN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| IA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| KS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KY | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| LA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| ME | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| MD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| MA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| MI | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| MN | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| MS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| MT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| NE | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| NV | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| NH | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| NJ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| NM | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| NY | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| NC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| ND | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| OH | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| OK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| OR | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| PA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| RI | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| SC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| SD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| TN | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| TX | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| UT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| VT | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| VA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| WA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| WV | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| WI | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| WY | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |