Jim Murphy

Introduction

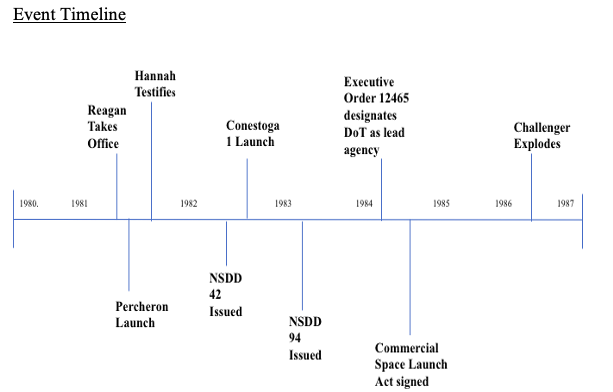

On September 9th, 1982, Space Services Incorporated of America (SSIA) launched into space the first privately funded rocket, the Conestoga 1.[1] The founder of SSIA, David Hannah Jr., hoped that like its namesake, the wagon that had carried settlers westward in the 1800s, the Conestoga would blaze a trail that opened new opportunities for pioneers. However, before a new trail could be blazed in outer space, Hannah had to find a path through the bureaucratic and legislative corridors of power in Washington DC.[2] The official obstacles to private space flight were so formidable, that only the direct and sustained intervention of officials in the administration of President Ronald Reagan had enabled SSIA’s launch to proceed. “SSIA early on received the support of the Reagan administration, in the person of White House Science Advisor Dr. George A. Keyworth, and engaged in a year-long effort to convince a variety of Federal agencies to approve the proposed launch.”[3] Hannah recognized that the future of his company and of private space ventures in general rested on a thorough re-examination of the disorganized and unclear legislation concerning the private sector in outer space. Only after the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984, which overhauled the process for licensing private rocket launches, did private exploration and utilization of space become practical.

After the Launch of the Conestoga 1 the founder of SSIA, David Hannah Jr., was invited to testify before Congress to suggest ways that the licensing process could be improved.[4] This is reason enough to look into the role that the SSIA and the Conestoga 1 played in the creation of new policy. I have no doubt that the Conestoga 1 was not the only reason for the creation of the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984 by the Reagan administration, but that it was the chief example of the problems with space policy in the private sector. Reagan was known for his ideologies of deregulating or streamlining policies to accommodate the private sector, as he thought that the private sector was more efficient than the public sector. Many of Reagan’s policy decisions were in response to create a better sense of security due to the growing threat of the Soviet Union. History shows that the Conestoga 1 was used as an example of how disorganization and unclear legislation regarding commercial space hinders the growth of the United States’ private sector in outer space. The Conestoga 1 rocket and the executives of Space Services Incorporated of America were massively influential in the creation of the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984 through their testimonies and interactions with the Reagan administration.

Scholars have disagreed about the reasons for the commercialization and privatization of outer space. Dr. Edythe E. Weeks Esq. as part of her comprehensive study of U.S. and international space law, Outer Space Development, International Relations and Space Law: A Method for Elucidating Seeds, arguesthat theReagan Administration used their distrust of the Soviet Union as justification to create policy for commercial opportunities in space to combat the Soviets space program.[5] Inher analysis, U.S. space policy in the time period between 1980 through 1990 revolved around the Cold War and the Arms Race, but created policy that was used in the future by other space capable entities.[6] She contends that the Reagan administration was excited to streamline the licensing process for commercialization of space and private space activities in order to reduce costs for NASA and incentivize the production of more advanced consumer goods. The Commercial Space Launch Act was the main piece of legislation facilitating the shift from public to private space activities.[7] Weeks identifies the Challenger explosion as justification for separating the public and private space activities and their goals and for the continued implementation of policy in the private space launch program.[8]

James Clay Moltz, in The Politics of Space Security: Strategic Restraint and the Pursuit of National Interests, agrees with Weeks. He believes that the Reagan administration tried to use the private sector for security purposes against the Soviet Union. The Arms and Space Race created growing security concerns for both superpowers that led to growing worries that the other was militarizing space[9]. Satellite installment and surveillance equipment being put into place impeded on the international treaties that already existed.[10] The growing fear of each superpower led to a new space race focusing on rockets that could establish satellites in space. Seeing that the US military could benefit from commercial space systems, the Reagan administration tried to make private launch technologies more accessible.[11] The greater cost efficiency of the private sector space launch systems made commercialization in space a security issue as well as a commercial opportunity for the United States.

John M. Logsdon, however, argues that the policy changes that were supposed to help cultivate a new era of private space enterprises were “premature” and slow.[12] He agrees with Weeks that the policy created in 1983-84 was the foundation for the growth and legitimacy of policy and of the private space sector, but he sees the launch of SSIA’s rocket, the Conestoga 1, as a mere symbolic victory for the private sector. Instead he credits the conclusions and recommendations from the Senior Interagency Group for Space [SIGS] as key to streamlining the process of licensing and launching in the future and concludes that the Challenger explosion in 1986 was the real catalyst that opened the door for the Reagan administration to push for more commercial based space programs. Both Logsdon and Weeks seem to agree that the Commercial Space Launch Acts and other policies put in place in 1983-84 were the foundation for growth of the private sector in space, but Logsdon sees the launch of SSIA’s rocket, the Conestoga 1, as a private sector success.[13] However, he sees the conclusions and recommendations from the Senior Interagency Group for Space [SIGS] as important to streamlining the process of licensing and launching in the future.[14]

Roger Handberg’s book, The Future of the Space Industry Private Enterprise and Public Policy, questions whether the need to streamline regulations for the private sector was an important factor. “Advocates of the private sector publicly rail against government policy obstructing their progress but then in other contexts reverse direction and insist even demand, government favors and subsidies effectively undermining both within the government and with the general public.”[15] He too discusses the Challenger explosion and how the public pride in and trust of the NASA space program had begun to fall, opening the door to private industry.[16] Handberg, like Weeks and Logsdon, suggest this loss of confidence in NASA explains why the U.S. decided to change policy to make it more inclusive to the private sector, allowing them to fund Expendable Launch Vehicles under the supervision of the FAA. The Reagan administration wanted the private corporations to take over the satellite launching program to replace old ones, but the proposal fell short when it came to economic and operational problems.[17] Handberg argues that, under Reagan’s administration, Congress actually was in favor of turning over the launching of satellites to private companies, but the logistics of the operation were not yet clear.

Henry W. Lambright and Diane Rahm argue that presidential backing was crucial to the success of space initiatives put forth by Congress. Space policy is extremely president centered and relies on the president to create goals and reach them.[18] When the president supports space related initiatives, they are more likely to come to fruition and succeed. However, in regard to the Commercial Space Act of 1984 they note, “While the emphases are unique to the Reagan years (for example, privatization and militarization),” the interactions of President, Congress, bureaucracy and other interest groups “actually [shaping] the policy [are] not unique.”[19]

Lawrence A. Cooper’s, Encouraging Space Exploration through a new application of Space Property Rights, discusses the impact that the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 would have on the future of private space endeavors. The Outer Space Treaty puts forth a basic framework for governance in space and revolves heavily around deterring any militarization of space. As well as to prevent sovereign nations from claiming any resources or celestial bodies in space in hopes that this will lead to a legal framework of property rights in space.[20] He also discusses the ways that the legal framework does not allow for commercial access to space through exploration, colonization, and mining. Without incentive there is no reason for states to move into space because there are not obvious motivations for the private sector to get involved in space exploration[21]. Private property rights are a means to motivate development in space and create opportunities for commercial expansion to collect resources.[22] The Moon Treaty and the Outer Space Treaty both have legal frameworks that describe property rights in space. They both ban states’ claim to resources as well as the individual. These documents, that have jurisdiction over U.S. legislation, were hampering the growth of the private sector in space due to the lack of incentives. Cooper argues that the regulations, both international and national, restricted the private sector from expanding into space due to the lack of commercial incentives. This indirectly relates to the Commercial Launch Act of 1984 that was put in place by the Reagan administration. This is important because one of Reagan’s reasons for having a commercial space program was to use United States companies to establish a sense of security against the Soviet Union and defeat them with the free market system.

W.D. Kay focuses on the Reagan administration’s efforts to “ease the regulatory tangle” and to develop new industry after the launch of the Conestoga 1 in 1982 but before the Commercial Space Launch Act in 1984.[23] She lays out the importance of the Conestoga 1 rocket by showing how it exposed the flaws in the political system that other private space companies would also have to use. Like Handberg, Kay points out the unpreparedness of the U.S. government to deal with private space companies and launches emerging in the early 1980’s. Both authors agree that the private companies want regulation, however, these companies search for regulation that is cheap for them and is in their best interest. Kay and Logsdon also allude to the role of Conestoga 1 in illustrating the crude governmental licensing procedure.

This essay will build on Kay’s argument about the key role played by the example of the Conestoga 1 and Space Services Incorporated in the passing of the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984. Using David Hannah Jr.’s and Donald Slayton’s testimonies before the Subcommittee on Space Science and the Applications of the Committee on Science and Technology of Congress, and materials from the Reagan administration officials, I will show that concerns over the bureaucratic obstacles to the launching of the Conestoga 1 rocket and expressed by SSIA executives were instrumental in the creation of the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984. The initiative taken by private industry (SSIA) fit perfectly with the Reagan administration’s drive for the deregulation and streamlining of policies and catalyzed a shift from a public to a private mindset in space and policy in the United States.

Reagan’s Ideologies

The job of the U.S. government, according to Ronald Reagan, is to serve as a framework so that the private citizens have security and opportunity. In Reagan’s first Inaugural Address he lays out his ideologies on the role of government. He elaborated on his intentions to “curb the size and influence” of the federal government but reiterates that he did not want to do away with the government but “make it work” and “foster productivity.”[24] Reagan did not deregulate for the sake of deregulation. He understood that the federal government has a role in the United States governing system.

Ronald Reagan’s advocacy for deregulation in favor of the private sector extended into his ideologies for space. In this specific case there was no legislation to deregulate which led to a metaphorical bog of red tape for commercial launch companies to drudge through. This was not a hospitable place for companies to thrive. This was not the type of commercial environment that Reagan envisioned for the United States.

Before the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984 there was no clear structure to help foster success in outer space for the private sector. Instead there were 18 federal agencies and 22 statutes that had to be navigated.[25] Simply eliminating all governmental regulations would lead to chaos so the Reagan administration’s goal was to create streamlined frameworks that would help the private sector succeed, creating a symbiotic system where the government and private sector helped each other. The goal was to streamline the system so that they can be efficient, instead of drowning in red tape from 18 different agencies. “The activities of the White House and the Reagan administration have been supportive of streamlining regulatory constraints in outer space, this is shown by Presidential Directives and Executive Orders in July 1982, February 1982, and July 1984, and the Commercial Space Launch Act.”[26]

Ronald Reagan’s advocacy for deregulation in favor of the private sector extended into his ideologies for space. In this specific case there was no legislation to deregulate which led to a metaphorical bog of red tape for commercial launch companies to drudge through. This was not a hospitable place for companies to thrive. This was not the type of commercial environment that Reagan envisioned for the United States. Reagan’s administration revolved around deregulation and beating the Soviet Union. A thriving commercial space program would help with both of those things. President Reagan and Congress also expressed interest in shifting over to commercialization by transferring communications technology to the private sector.[27] The Committee on Science and Technology in the US House of Representatives report dated April 15, 1983 stated “that we should establish a policy which would encourage commercialization of space technology to the maximum extent feasible, and the committee on commerce, science, transportation, U.S. endorsing the efforts by the private sectors to invest and seek commercial opportunities in space.”[28] So how does the launching of a small rocket funded by private citizens coincide with this effort to capitalize on the administration’s goals? The connections come in the form of people: politicians, scientists, businessmen, lawyers, rocketeers, astronauts, and department heads. It must start with one person, and that person was a well-connected real estate titan from Texas named David Hannah Jr.

Hannah & SSIA

In 1981, just as the Reagan admiration and Congress began considering steps for the commercialization of space, a real estate titan from Texas, David Hannah Jr. created Space Services Incorporated of America with the idea of lowering the cost or access to space.[29] Later that year on August 5, 1981 the company’s first rocket, the Percheron, blew up on the launch pad.[30]This did not deter Hannah. He hired Donald “Deke” Slayton, a former astronaut for NASA, as president of his small private space company. The failure of the first rocket actually gave them a great amount of press and support from around the country. It may have also helped that Hannah was friends with local national politician, Vice President George H.W. Bush, who pointed them in the direction of George A. Keyworth, Ronald Reagan’s head science advisor. Keyworth immediately offered his support for the company. He met with David Hannah Jr. and discussed SSIA’s views on the government’s involvement in regulating private space flight.[31] Hannah also testified before the Subcommittee on Space Science and the Applications of the Committee on Science and Technology in September of 1981, after the failed launch of his first rocket. While the rocket never got off the ground it was still a media success that led to the plans for the Conestoga 1.

Between 1981 and 1984, the two executives of SSI, Hannah and Slayton, testified multiple times to the Senate and the House Subcommittees on Space Science and the Applications of the Committee on Science and Technology. The suggestions from Donald Slayton and David Hannah Jr. in their testimonies, aligned almost precisely to the Commercial Space Launch Act’s stated purposes. In September 1981, even before the launch of the Conestoga 1, Hannah offered five main suggestions to the Subcommittee that were derived from SSIA’s experience with their first rocket the Percheron. The first was the necessary appointment of a lead agency. The second was the process for approval for launch site usage and the regulations that would have to be adhered to. The third discussed the liability regulations and the international laws that would be inherently involved in any space launch by the United States public or private. The fourth was that the United States government should encourage the private sector to get involved in space as long as they are doing so in a legal way. The fifth and final point was that the U.S. government should recognize the private sector in space and utilize it to assert the dominance of the U.S. in space.[32] Hannah argued that without encouragement from the U.S. government, the private sector lacked a clear path to space, which proved just as problematic as harsh regulations.

Hannah mainly wanted to urge the United States government to create a more streamlined way for private companies to have access to space by dedicating a lead agency to regulate space flight.[33] The problem with the system at the moment is that too many departments were involved in the licensing process because there was no legislation for private space launches. Jason E. Steptoe, former General Counsel who specialized in international aerospace and trade law for theU.S. Department of Transportation, puts this into perspective:

Initial consideration of SSI’s application immediately revealed that a number of Federal agencies could claim either direct or indirect regulatory interests in the issues presented by the application. These included matters as diverse as transporting hazardous materials, gaining access to Government radio frequencies, launching through controlled airspace, and even the issuance of a license from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms of the Treasury Department for importation of firearms. No agency, however, appeared to have direct responsibility for licensing the actual launch. Consequently, a decision was made by members of a senior interagency group on space, operating under the aegis of the National Security Council, to rely upon the Department of State’s authority under Section 38 of the Arms Export Control Acts and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), issued pursuant to that Act, as the umbrella authority under which the Federal Government would discharge its international and municipal legal obligations to authorize and supervise the proposed launch. In essence, a private space launch was to be treated as an export of a munition into space and would be regulated under the ITAR.[34]

One could see how this would become a problem when trying to get approval for licensing of launching and launch pads. This jumble of regulations and agency involvement also made it monetarily impractical for private companies to get involved in space. Hannah knew this and brought this to the attention of the U.S. government. The Conestoga 1 launch was unique because it was not a satellite launch, so it needed new legislation and licensing policies. This also shows the request by the SSIA to launch the Conestoga 1 raised important questions as to how the policies of the treaties and governments would be handled on a private individual basis.[35] This request forced the government to look into the private launch policies more than they had before. They had to put a new focus on private launches because they did not have the policies to handle the situation.

Hannah understood that the system did not work, and he was actively trying to change them through his testimony. Meanwhile Ronald Reagan involved himself in the privatization of space even before the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984. “On July 4, 1982, President Ronald Reagan issued National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) 42, “National Space Policy,” stating that the expansion of U.S. private sector involvement in civil space activities was a national goal.[36] On May 16, 1983, the President issued NSDD 94, “Commercialization of Expendable Launch Vehicles.” This stated the “U.S. Government fully endorses and will facilitate the commercialization of U.S. Expendable Launch Vehicles. The U.S. Government will license, supervise, and/or regulate U.S. commercial ELV operations only to the extent required to meet its national and international obligations and to ensure public safety.”[37] This showed once again that the ideologies of President Reagan aligned with the executives of Space Services Incorporated. Reagan showed his willingness to incorporate the private sector into the launching of Expendable Launch Vehicles (ELVs). ELVs could only be used once, which made them expensive to build and launch. Hence, NASA needed the help of the private sector to cut costs and build rockets on time. After the successful flight of the Conestoga 1 in 1982Ronald Reagan personally congratulated Hannah on his trailblazing venture.[38] This is an example of Reagan’s personal support for Hannah and SSI in their commercial space endeavors.

Hannah’s arguments also received support from another SSIA executive, retired NASA official, and former head of the Goddard Space Center, Arthur L. Levine. Levine shared the opinion that the private sector performs more efficiently than government and that deregulation is important for the growth of private activity in space.[39] Writing in 1985, Levine echoed Hannah’s argument about the need for streamlining of the launch licensing process.He insisted that legislators must examine the commercial impact on the U.S. and the impact on international relations,[40] At the time, in 1985, the discussion on space policy was largely between the government and its agencies involved in space exploration. This did not generally include private entities. There was no policy that governed the impacts of commercialization on the U.S. civilian space program. There was no clear path for private companies to be licensed. Levine, however, recommended caution. Rather than simply opening up space for profit, he believed that policies must make sure that the private corporations’ intentions in space were governed so that they promoted growth of industry and were in the public’s interest.

Other voices also expressed concern about a complete laissez faire approach to space by the U.S. government. James R. Myers argued that governments’ relationship with the private sector must be one of guidance but not control. While government officials in both political parties in Congress and Federal agencies had strongly supported U.S. commercial ventures, they had not given over total control.[41] They do not give over total control because they still want to make sure that the private sector is working in the public’s interests. Another of the founders of SSIA, Art Dula, also advocated for the privatization of space. Dula was a “champion of commercial space flight and a recognized space attorney.[42] Like Hannah, he testified that the example of the Conestoga 1 rocket, developed by SSIA, ran into multiple issues caused by the abundance of regulations and policies that made it too difficult to launch a profitable commercial rocket. State, federal, and international laws and treaties had to be reviewed when considering the launch of Conestoga 1. Dula believed that deregulation was the way to get companies to invest in space and make it available and fiscally beneficial.[43] The Conestoga 1 rocket that was developed by the SSIA ran into multiple issues due to the abundance of regulations and many departments involved in the licensing process.[44] These regulations and policies made it too difficult to launch a profitable commercial rocket, as state, federal, and international laws and treaties had to be reviewed when considering the launch of the Conestoga 1. If those remained, it would be too complicated to launch a commercial rocket that would be a worthwhile investment for the company.

Hannah and the other SSIA executives influenced by the Reagan administration was clear in the Presidential Directive on the Commercialization of Expandable Vehicles “encouraging a private sector development of commercial launch operations.”[45] This Executive Order (12465- Commercialization of Expendable Vehicles) was Reagan’s biggest direct contribution to the streamlining of the commercial launch system. By designating the Department of Transportation as the lead agency and explaining its responsibilities, he directly addressed Hannah’s first concern streamlining the process and encouraging private ventures. The Executive Order laid out that the Secretary of Transportation shall, to the extent permitted by law and subject to the availability of appropriations, perform the following functions:

(a) act as a focal point within the Federal government for private sector space launch contacts related to commercial ELV operations;

(b) promote and encourage commercial ELV operations in the same manner that other private United States commercial enterprises are promoted by United States agencies;

(c) provide leadership in the establishment, within affected departments and agencies, of procedures that expedite the processing of private sector requests to obtain licenses necessary for commercial ELV launches and the establishment and operation of commercial launch ranges;

(g) identify Federal statutes, treaties, regulations and policies which may have an adverse impact on ELV commercialization efforts and recommend appropriate changes to affected agencies and, as appropriate, to the President.”[46]

With the Department of Transportation now clearly identified as the lead agency responsible for facilitating and coordinating the development of commercial space launch operations, Reagan appointed Jennifer Dorn as the director.[47] Jason E. Steptoe explained:

Successful commercial development of space technologies requires that the private sector has assured access to space, and an increasing number of private firms are eager to provide that access a critically important corollary to that effort is the Government’s commitment to devising a licensing program which is both responsive to public concerns as well as sensitive to private commercial needs.[48]

This is precisely what happened. After the testimony from Hannah and the launch of his first rocket, Reagan and his administration used Executive Orders and Presidential Directives to help facilitate commercial space policy and practices.

The Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984

However, Reagan’s executive action set the stage for the Congressional Action. Again, the influence of Hannah’s testimony seems clear. Indeed, a comparison of Hannah’s stated goals and the purposes of the act are too similar to be coincidental. The language used to explain the purpose of the Act seems to have been modeled directly on the framework provided by Hannah’s testimony.

…. The purpose of this Act is —

(1) to promote economic growth and entrepreneurial activity through utilization of the space environment for peaceful purposes;

(2) to encourage the United States private sector to provide launch vehicles and associated launch services by simplifying and expediting the issuance and transfer of commercial launch licenses and by facilitating and encouraging the utilization of Government-developed space technology; and

(3) to designate an executive department to oversee and coordinate the conduct of commercial launch operations, to issue and transfer commercial launch licenses authorizing such activities, and to protect the public health and safety, safety of property, and national security interests and foreign policy interests of the United States.[49]

Hannah asked for the government to encourage the private sector, and one of the three purposes of this act is to encourage the private sector to provide launch vehicles and services to lower the cost of launches. Hannah knew that the private sector was the key to dominating space and the third purpose of the act was to “protect the public health and safety, safety of property, and national security interests” in space. Reagan and his administration’s ideologies on the commercial space legislation were shared with Hannah. Hannah’s suggestions align with Reagan’s mission which lead to the creation of the Commercial Space Launch Act.

Slayton’s Testimony

The testimony of Donald Slayton, the other key player at SSI, before the Senate Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation on September 6, 1984 regarding the Commercial Space Launch Act reconfirmed the important role played by the Conestoga 1 launch and Hannah’s testimony. Slayton expressed his gratitude for the Commercial Space Launch Act on behalf of all private space companies,

…the Commercial Space Launch Act is a logical and necessary follow-on in the development of private enterprise in space. Your support for entrepreneurial space efforts has inspired us to continue to pursue the challenge of commercialized space. We strongly support the bill.[50]

Slayton went on to discuss the importance of the Department of Transportation as the lead agency to the process agency to streamlining licensing and clearances for Expendable Launch Vehicles.[51] In doing so he reflected on the SSIA’s experience in launching the Conestoga 1 rocket, implying that this launch exposed the weaknesses in the commercial space legislation:

…your legislation will streamline future ELV clearances. Enactment of the bill will provide the U.S. ELV industry with the certainty needed to attract our investment, as well as a regulatory climate to its manning our customer base. As you know, we launched the Conestoga once from a private site due to the absence of a policy allowing for private ELV launches in Government facilities and the lack of a regulatory guidance for user’s fees. Our experience working with the Government to obtain the necessary clearances for the first privately funded and operated launch, Conestoga I in 1982, set a crucial precedent regarding the regulatory framework in which commercial launch ventures operate. The U.S. Government made certain technologies available to us. They did clear the regulatory barriers which might have prevented us from accomplishing our goal. However, there were multiple agencies involved which complicated the approval process. Moreover, the lack of a clear policy guidance resulted in a significant expenditure for legal fees just to penetrate the regulatory morass.[52]

This statement by Slayton basically named SSIA and the launch of the Conestoga 1 as the groundbreaking launch for commercial launch ventures. By laying out the problems with the licensing and launching that SSIA encountered with their rockets, Slayton established that the Conestoga 1 set the “precedent” for creating the framework of commercial space launches in the United States.

Conclusion

From the failure of the Percheron, to the success of the Conestoga 1, Space Services Incorporated’s executives David Hannah Jr. and Donald “Deke” Slayton had an enormous impact on the creation of the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984. Their personal experiences with bureaucratic roadblocks and chaotic regulations made them ideal witnesses for the Congressional committees and lent their suggestions considerable weight. It certainly helped that their opinions aligned so closely with the Reagan administration’s goals of streamlining government programs. The administration in turn could use SSI as a model for necessary deregulation. Long before the Challenger disaster, SSI had already laid the groundwork for American companies to explore and commercialize outer space. Arguably, their pioneering efforts also helped build a foundation for international agreements on commercial space launches and set the stage for the globalization of outer space. Later administrations built upon the policy that the Reagan administration put in place in the 1980’s. For example, the groundbreaking Space Competitiveness Act, which was signed by President Barack Obama in 2015, and allowed for private companies of the United States to claim assets in space.[53] Moreover since the 1980’s there has been a dramatic growth in private space companies, both foreign and domestic. Companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic now undertake private as well as public-private ventures like taking satellites or supplies to outer space. [54] For instance, SpaceX delivered the first private resupply of the International Space Station in 2010, which showed private and public cooperation in the space launch industry.[55] The development of this American-led commercial space industry that is so vital for the continued exploration and utilization of outer space owes much to the early efforts of David Hannah Jr. and President Ronald Reagan.

Work Cited

Primary Sources

Art Dula. Chairman, Founder. Excalibur Almaz: Space Business Solutions, Accessed March 31, 2020. http://www.excaliburalmaz.com/pdf/bio_dula.pdf

Dula, Art. “Private Sector Activities in Outer Space,” International Lawyer (ABA) 19, no. 1 (Winter 1985): 159-188. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=hein.journals/intlyr19&id=189&men_tab=srchresults

Reagan, Ronald. “Executive Order 12465—Commercial Expendable Launch Vehicle Activities.” White House: Washington D.C. February 24, 1984. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. Accesses March 30, 2020. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/research/speeches/22484b

Regan, Ronald. 1st Inaugural Address. January 20, 1981. Ronald Reagan Library & Museum. Accessed April 14, 2020. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/research/speeches/inaugural-address-january-20-1981

Reagan, Ronald, Letter. September 27, 1982. The White House: Washington D.C. Accessed on March 30, 2020. https://dae08dca-e4b8-4b67-916b-8812b3f8f969.filesusr.com/ugd/32931c_6cf057d0e7d744e29c2cf37d2beba9b4.pdf

Reagan, Ronald. “Statement on Signing the Commercial Space launch Act.” October 30, 1984. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. Accesses March 30, 2020. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/research/speeches/103084i

“The Launch of Conestoga 1.” Space Services Incorporated of America, Accessed March 10, 2020. https://www.spaceservicesinc.com/conestoga-1

US House of Representatives. Hearing. Testimony of David Hannah, Jr. the president of Space Services Incorporated before the Subcommittee on Space Science and the Applications of the Committee on Science and Technology, 92-109. Washington D.C. US Government printing Office, 1981. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=O9TVAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA100&lpg=PA100&dq=david+Hannah,+Jr.+testimony+in+congress&source=bl&ots=WOC8_sg33P&sig=ACfU3U12hRr_GnflBIDJoPWL0kdlY3WGAA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjt_cPQ1tnnAhVoHjQIHZm1BxcQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=david%20Hannah%2C%20Jr.%20testimony%20in%20congress&f=false

US Senate. Hearing. Donald Slayton before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce Science, and Transportation. Ninety-Eighth Congress, first session. Commercial Space Launch Act. Washington D.C., US Government Printing Office September 6, 1984. Google Books. https://books.google.com/books?id=61C5H004EpIC&pg=RA1-PA48&dq=how+ronald+reagan+changed+commercial+space+policy&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj28J3GtL3nAhWKgXIEHfPpBRcQ6AEwBHoECAEQAg#v=onepage&q&f=false

Woods, Michael. Rocket Failure Brings Favorable Fame: Private Effort ended in Launch Explosion. The Blade. Toledo, Ohio: September 23, 1981, 25.

Secondary Sources

Cooper, Lawrence A. Encouraging Space Exploration through a new application of Space Property Rights. Sciencedirect.com. Elsevier, 2003, Accessed February 2, 2020. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S026596460300016X

Handberg, Roger, foreword by David C. Webb. The Future of the Space Industry Private Enterprise and Public Policy. Westport, Connecticut: Quorum Books, 1995.

Kay, W.D. Defining NASA: The Historical Debate over the Agency’s Mission. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2005. Accessed March 11, 2020. https://www.mobt3ath.com/uplode/book/book-36072.pdf

Lambright, Henry W, and Diane Rahm. “Ronald Reagan and Space Policy.” Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 17, No.3, 1989.

Levine, Arthur L. “Commercialization of Space: Policy and Administration Issues.” Public Administration Review 45, no. 5 (1985): 562-69. Accessed February 6, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3109931

Logsdon, John M. Ronald Reagan and the Space Frontier, 1st ed. Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland:Palgrave Macmillan. 2019.

Moltz, James Clay. The Politics of Space Security: Strategic Restraint and the Pursuit of National Interests, 2nd ed. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Myers, James R. “US Commercial Space Ventures.” Harvard International Review 7, no. 5 (1985): 39-43. Accessed February 3, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/42760856

“Origins of the Commercial Space Industry.” Federal Aviation Administration. US Government. Accessed February 8, 2020. https://www.faa.gov/about/history/milestones/media/commercial_space_industry.pdf

Solberg, Andrew. “Arthur Levine Interview: Oral History Project.” The Baker Street Irregular Trust. Published September 14, 2016, accessed March 31, 2020. http://www.bsitrust.org/2016/10/arthur-levine-interview-oral-history.html

Steptoe, E. Jason, “United States Government Licensing of Commercial Space Activities by Private Enterprise” (1985). Documents on Outer Space Law. 7. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/spacelawdocs/7

Wagner, Scarlet. #SpaceWatchGL Perspective On US Space Resources Executive Order: IISL President Kai-Uwe Schrogl On The Clarity Of Existing Space Law. International Institute of Space Law. Published April 19, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020. https://iislweb.org/spacewatchgl-perspective-on-us-space-resources-executive-order-iisl-president-kai-uwe-schrogl-on-the-clarity-of-existing-space-law/

Ward, Peter. The Consequential Frontier: Challenging the Privatization of Space. Brooklyn, New York: Melville House Publishing, 2019.

Weeks, Edythe E. Dr. Esq. Outer Space Development, International Relations and Space Law: A Method for Elucidating Seeds. New Castle, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012.

[1] “The Launch of Conestoga 1.” Space Services Incorporated of America, published 2012, Accessed March 10, 2020.

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] Weeks, Edythe E. Dr. Esq. Outer Space Development, International Relations and Space Law: A Method for Elucidating Seeds, New Castle, United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012,59.

[6] ibid.

[7] Weeks, Edythe E. Dr. Esq. Outer Space Development, International Relations and Space Law: A Method for Elucidating Seeds, 65.

[8] ibid., 74.

[9] Moltz, James Clay. The Politics of Space Security: Strategic Restraint and the Pursuit of National Interests, 2nd ed. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2008, 5.

[10] ibid., 344-345.

[11] ibid., 344-345.

[12] Logsdon, John M. Ronald Reagan and the Space Frontier, 1st ed. Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland:Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, 179.

[13] Logsdon, John M. Ronald Reagan and the Space Frontier, 179.

[14] ibid., 182.

[15] Handberg, Roger, foreword by David C. Webb. The Future of the Space Industry Private Enterprise and Public Policy. Westport, Connecticut: Quorum Books, 1995, 2.

[16] ibid., 18.

[17] Handberg, Roger, foreword by David C. Webb. The Future of the Space Industry Private Enterprise and Public Policy, 59.

[18] Lambright, Henry W, and Diane Rahm. “Ronald Reagan and Space Policy.” Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 17, No.3, 1989. 515.

[19] ibid., 516.

[20] Cooper, Lawrence A. Encouraging Space Exploration through a new application of Space Property Rights. Sciencedirect.com. Elsevier, 2003, Accessed February 2, 2020.

[21] Cooper, Lawrence A. Encouraging Space Exploration through a new application of Space Property Rights.

[22] ibid.

[23] Kay, W.D. Defining NASA: The Historical Debate over the Agency’s Mission. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2005. Accessed March 11, 2020.

[24] Regan, Ronald. 1st Inaugural Address. January 20, 1981. Ronald Reagan Library & Museum. Accessed April 14, 2020.

[25] Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce Science, and Transportation. Ninety-Eighth Congress, first session. Commercial Space Launch Act. Washington D.C., US Government Printing Office September 6, 1984. Google Books, 22.

[26] Cooper, Lawrence A. Encouraging Space Exploration through a new application of Space Property Rights.

[27] Weeks, Edythe E. Dr. Esq. Outer Space Development, International Relations and Space Law: A Method for Elucidating Seeds, 65.

[28] ibid., 68.

[29] Logsdon, John M. Ronald Reagan and the Space Frontier, 179.

[30] Woods, Michael. Rocket Failure Brings Favorable Fame: Private Effort ended in Launch Explosion. The Blade. Toledo, Ohio: September 23, 1981, 25.

[31] Logsdon, John M. Ronald Reagan and the Space Frontier, 179.

[32] US House of Representatives. Hearing. Testimony of David Hannah, Jr. the president of Space Services Incorporated before the Subcommittee on Space Science and the Applications of the Committee on Science and Technology, 92-109. Washington D.C. US Government printing Office, 1981. Google Books, 95-96.

[33] ibid.

[34] Steptoe, E. Jason, “United States Government Licensing of Commercial Space Activities by Private Enterprise” (1985).

[35] Steptoe, E. Jason, “United States Government Licensing of Commercial Space Activities by Private Enterprise” (1985). Documents on Outer Space Law, 7.

[36] “Origins of the Commercial Space Industry.” Federal Aviation Administration. US Government. Accessed February 8, 2020. 1

[37] Origins of the Commercial Space Industry.” Federal Aviation Administration, 7.

[38] Regan, Ronald, Letter. September 27, 1982. The White House: Washington D.C. Accessed on March 30, 2020.

[39] Levine, Arthur L. “Commercialization of Space: Policy and Administration Issues.” Public Administration Review 45, no. 5 (1985): 562-69. Accessed February 6, 2020.

[40] ibid.

[41] Myers, James R. “US Commercial Space Ventures.” Harvard International Review 7, no. 5 (1985): 39-43. Accessed February 3, 2020.

[42] Art Dula. Chairman, Founder. Excalibur Almaz: Space Business Solutions, Accessed March 31, 2020.

[43] Dula, Art. “Private Sector Activities in Outer Space,” International Lawyer (ABA) 19, no. 1 (Winter 1985): 159-188.

[44] ibid., 179.

[45] US Senate. Hearing. Donald Slayton before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce Science, and Transportation. Ninety-Eighth Congress, first session. Commercial Space Launch Act, 69.

[46] Reagan, Ronald. “Executive Order 12465—Commercial Expendable Launch Vehicle Activities.” White House: Washington D.C. February 24, 1984. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum. Accesses March 30, 2020.

[47] Myers, James R. “US Commercial Space Ventures.” Harvard International Review 7, no. 5.

[48] Steptoe, E. Jason, “United States Government Licensing of Commercial Space Activities by Private Enterprise” (1985). Documents on Outer Space Law, 7.

[49] US Department of the Treasury, Report of the Secretary of the Treasury Transmitting a Report from the Register of the Treasury of the Commerce and Navigation of the United States for the Year Ending the 30th of June, 1850, 31st Cong., 2d sess., House Executive Document 8 (Washington, DC, 1850-51).

[50] US Senate. Hearing. Donald Slayton before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce Science, and Transportation. Ninety-Eighth Congress, first session. Commercial Space Launch Act. Washington D.C., US Government Printing Office September 6, 1984. Google Books, 58.

[51] US Senate. Hearing. Donald Slayton before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce Science, and Transportation. Ninety-Eighth Congress, first session. Commercial Space Launch Act., 58.

[52] US Senate. Hearing. Donald Slayton before the Subcommittee on Science, Technology, and Space of the Committee on Commerce Science, and Transportation. Ninety-Eighth Congress, first session. Commercial Space Launch Act, 58.

[53] Wagner, Scarlet. #SpaceWatchGL Perspective On US Space Resources Executive Order: IISL President Kai-Uwe Schrogl On The Clarity Of Existing Space Law. International Institute of Space Law. Published April 19, 2020. Accessed April 27, 2020.

[54] Ward, Peter. The Consequential Frontier: Challenging the Privatization of Space. Brooklyn, New York: Melville House Publishing, 2019. 45-46.

[55] Ward, Peter. The Consequential Frontier: Challenging the Privatization of Space, 68.