By: Jenn Jungclaus

Most people have a certain understanding of what a horror film is, namely, that it is emotionally juvenile, ignorant, supremely non-intellectual and dumb. Basically stupid. But I think of horror films as art, as films of confrontation…. Just because you’re making a horror film doesn’t mean you can’t make an artful film. Tell me the difference between someone’s favourite horror film and someone else’s favourite art film. There really isn’t any. Emotions, imagery, intellect, your own sense of self.

-David Cronenberg

On a dark night during Halloween 1984 I was watching television alone in my family’s living room. The classic zombie film, Night of the Living Dead, was playing, and surrounded by stuffed animals, snacks and a blanket, I was settling in to watch the movie. My mother walked into the room, looked at the screen, sighed deeply and said, “You shouldn’t be watching this. It’s not for ladies.” However, she was too exhausted to care any further and continued with whatever task she was doing. A few years later, she came into my room to put away some newly washed clothes and found me watching A Nightmare on Elm Street. “Jennifer,” she said with exasperation, “This isn’t for ladies.” This time, though, I considered what she meant. In my opinion, the film was brilliant. A crazed psycho killer takes revenge on the children of the men and women who had hunted him down and killed him. He does this in the most inescapable way there is… in their dreams. One could drink coffee all day or take drugs to remain awake, but sooner or later one’s body would succumb and require sleep. There is no way around it. In the end, however, the killer is destroyed by a strong, smart and clever girl who figures out how to defeat him by using her brain rather than brawn. In my opinion, it didn’t get any better than that. Why then did my mom not find this suitable entertainment for a “lady?”

Years later when my passion and interest in horror films had not subsided, I asked my mother what she meant by her previous criticisms of her daughter watching horror films. Her response was one similar to those echoed in countless reviews of horror films and the horror genre in general. That is, these films hate females and are just a way for people (men) to act out their violent fantasies on women without getting in trouble. These films are of no value and the women portrayed in them all had big boobs and no brains. Slasher movies were simply gratuitous sex and gory violence. Again, I had to think about that. How could it be that films that supposedly “hate females” spoke so deeply to me, a female? I did not hate women. I was not a violent person and did not feel that I was vicariously living out some morbid fantasy. Admittedly, the stereotypical “blond bimbo” does exist in these films but there were female heroines in them too who figured out how to survive when so many others, both male and female, could not do so. These women who were courageous, resourceful and admirable. Horror films, specifically the slasher sub-genre, not only had a place for feminism, but that place was where women could thrive and shine. In an industry that is largely imagined to be a boy’s club that tells gory and violent stories, is there a place for strong women? Did the slasher films of the 1970s and 1980s represent a kind of backlash against the feminist movement that happened shortly before the films were created, or were these films an outrageous and exaggerated way to highlight gender issues and the true ability of women?

The horror genre as a whole does not generally garner much respect, seldom being viewed through a serious lens. There are many sub-genres to horror: torture, home invasion, undead, virus, possession, and slasher to name but a few. The slasher film sub-genre saw its “golden era” starting around 1978 and continuing until 1984. Horror director Karen Lam has observed, “Every time I hear, ‘I don’t like horror’ it’s usually because they don’t like slashers.”[1] Author Carol Clover has described slasher films as being, “at the bottom of the horror heap,” and “beyond the purview of the respectable (middle-aged, middle-class) audience.”[2] Even author and avid horror fan Isabel Cristina Pinedo called the sub-genre, “the most disreputable form of the horror film.”[3] Still, slasher films are typically the kind of genre people imagine when the topic of horror is discussed. They are one of the easiest to define, and their villains are often the most iconic. They are also largely lampooned and quickly dismissed for the graphic violence, misogyny and abundant nudity. In her seminal book, Men, Women and Chainsaws, Carol Clover laid out a set of criteria that she used to define a slasher film. Her list includes the killer, the victim, the location or the Terrible Place, the weapon and the Final Girl. It is the Final Girl who makes it to the end of the film and is tasked with killing, or escaping from, the killer on her own.[4]

Critically, Slashers have never done well in the mainstream. In 1984, movie critics Gene Siskel and Robert Ebert named Friday the 13th as one of the worst films of the year. They were not shy in expressing their disappointment when telling their audience that a sequel was already in the works.[5] A 1978 review in The New Yorker by critic Pauline Kael railed against John Carpenter’s Halloween, saying that he “doesn’t seem to have any feeling at all for motivation or for plot logic.” She called the script “pitiful.”[6] A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) fared slightly better with critics due in part to its unique, surrealist spin on the typical slasher story. Its theme is that the only thing as inevitable as death is sleep. The story’s creator, Wes Craven, used his characters’ dreams as the film’s killing ground. That, coupled with the film’s particularly good special effects (especially when considering its relatively low budget of 1.8 million dollars[7]), earned it moderately good reviews. However, even some of those solid reviews acknowledged how little consideration is typically given to horror films. James Berardinelli of ReelViews said the film was “tailor made for those who like their gore leavened with thought-provoking ideas – something that is a rarity in this genre.”[8] These kinds of attitudes and the lackluster language towards slashers is reflective of how marginalized the genre is in the minds of movie goers and within the film industry.

On the surface, it is not difficult to see why the films are perceived as low brow entertainment just teetering on pornographic. Without question, there is a lot of teen sex in these films that is almost always followed up by the brutal killing of one or both parties. Promiscuity in slashers, especially in young females, is almost always followed by a swift and violent death. Feminist and author Susan Faludi argues that this kind of portrayal of independent women in films and television in the 1980s was a common tactic used to silence the female voice. Although she does not specifically address slasher films, she generalizes that during this time in Hollywood, “women’s lives were framed as morality tales in which the ‘good mother’ wins, and the independent woman gets punished.”[9] In essence, that argument is similar to what others have said about slasher films. That is, the promiscuous girls always die in merciless ways and the “pure” and “virginal” girls survive in the end. However, the girls in slashers do not die because they were having sex nor do those survive because they are virgins. If one’s purity provided salvation in these films, then the killer would not be hyper-focused on killing them in the first place. The killer is trying to kill the “pure” girls as much as anyone else, if not more so. Attributing their survival to their virtue diminishes the girl’s cleverness, resiliency and heroism.

A study of three of the biggest slasher films of the time, Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, John Carpenter’s Halloween and Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street, will demonstrate why slasher films should be given more serious consideration when discussing history, art, and feminism in film. These films are emblematic of societal issues in the era in which they were produced. Whether the issue is gender, race relations, fear of foreign entities, concerns over pollution, religious conflict or others, horror films are in a unique position to reflect to their audiences issues that they may already be aware of but unable to do much about. Thus, these films become a sort of cathartic and empowering experience for the viewer. University of Pittsburgh Professor Adam Lowenstein articulated this idea best by saying, “It’s the horror film that’s actually able to engage traumatic history and to confront viewers with it. And it’s largely because the horror film is already equipped with the tools to shock us, to unsettle us, to disturb us. It’s not the place most people would think of as where history is happening. It’s precisely that preconception that allows things to go on in relation to history.”[10]

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

Generally considered the first true slasher film and one of the most gruesome is the 1974 movie, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Filmed in a home movie style, it has been described as being, “like the footage from a nightmare.”[11] The general plot of the film is five friends drive through Texas on a weekend trip to visit their grandfather’s grave site and end up falling victim to a family of cannibalistic psychopaths. While delayed on their trip due to an out of gas fuel station (this is a reference to the oil crisis of 1973),[12] they decide to wait until the next fuel delivery. It is while waiting that they become prey. They are systematically slaughtered in some of the most chilling scenes found in cinema. The film is often cited as being based on the notorious murderer and grave robber Ed Gein. While some inspiration may have been taken from Gein, the real symbology of the film is the broken nation in the post-Vietnam era.

The United States ended its official involvement in the Vietnam conflict in April 1975. In the ten years of active engagement, the war had cost the nation not only an incredible amount of money but nearly 60,000 lives, as well. The economy was in a significant decline and the patriotic high the nation had been on in the years following World War II had faded into discontent and uncertainly. Soldiers returning home from Vietnam did not return to cheers and parades like their WWII counterparts, but rather to hostility, unemployment, homelessness, and burdened with tremendous medical and psychological scars. When asked about the atmosphere surrounding the film’s production, director Tobe Hooper said, “The times were political. And the times were steeped in Vietnam.”[13] Although the war was never directly addressed in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the film captured the despondent mood of the country. The desolate setting, the minimalist approach in filming, and the horror lying just beneath the surface, ready to strike at the slightest hint of vulnerability, made The Texas Chainsaw Massacre a true sign of its time.

The film centers around a family of cannibal killers that butcher their victims like cattle. Using young adults as the films victims is a not so subtle comparison to sending kids just barely out of high school to war to be slaughtered. The tools they use, chainsaws, hammers, and meat hooks, are all tools of those belonging to a soon to be by-gone era. Sexuality is not the killer in this film, as is generally alleged to be for slasher films, but rather youth and accessibility are the victims’ downfalls. The family simply sees the young people as meat.

The most iconic member of the family is a large man, known only as Leatherface. This character is suggestive of killer Ed Gein. Known as the “Butcher of Plainfield,” Gein was a notorious murderer and grave robber who operated in the 1950s and 1960s. He confessed to killing two women (although he was suspected of more), but it is what he did to their bodies and the bodies of recently deceased women that made him infamous. When police raided his home, they found that Gein used women’s body parts to make lamp shades, seat coverings, bowls, pants, and a mask. Tobe Hooper took this grisly idea and applied it to Leatherface, who also wears a mask made from human skin.

Upon reflection of this movie, horror film director Eli Roth commented, “If you think about the landmarks, Psycho and Halloween, clearly the bridge between the two is Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.”[15] The movie was the start of realism in horror and a grittier style of filming. It was not, however, a film for the masses. While many films had been made about psychopaths, this film gave the impression that it was actually produced by one. It was too much for the general public to take. The horror genre would not enter mainstream until four years later with the premiere of Halloween.

Halloween

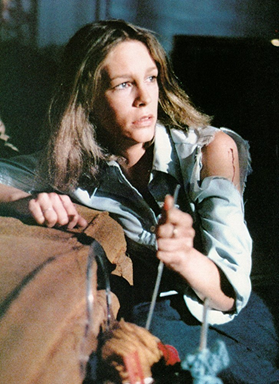

John Carpenter’s classic Halloween is often credited with bringing in the golden era of slashers. The premise is simple. A silent, masked killer named Michael Myers has escaped a psychiatric facility. He then returns to his hometown of Haddonfield, Illinois, fifteen years after murdering his sister to go on another killing spree. Knowing that his patient is dangerous, Michael’s psychiatrist, Dr. Loomis, is in hot pursuit. Once home, Michael fixates on a young girl named Laurie Strode and stalks her throughout the day. She notices the large, masked man quietly staring in her direction. Although he makes her instantly uneasy, she initially dismisses her concerns because it is the day before Halloween, a time when costumes and pranks are normal. Only after seeing him again does she expresses any concern to friends, who fail to take her seriously. Unfortunately for her friends, it was not a Halloween trick, and one by one, they are killed off until only Laurie and Michael are left alive.

In the years leading up to the film’s premiere in October 1978, the United States had just seen a string of high-profile serial killers. The Zodiac Killer, the Son of Sam, the Hillside Strangler and, perhaps the most prolific, Ted Bundy, all operated just before Halloween was released. These men predominantly sought and killed young women, although men were sometimes collateral victims as well. With over sixty confirmed victims among them and many more suspected, their presence terrified a nation. In the minds of many, they were the boogeymen, nameless, faceless men hiding in the shadows, who killed without emotion or remorse, with no obvious motive other than the sheer thrill of it. Newspapers and evening news programs warned women of the dangers of traveling alone, offering tips on how to stay safe. Though with few clues as to whom the men were, and no way to know when or where they would strike again, people remained afraid.

One particularly chilling case that left the nation shocked and on edge was the Chi Omega killings in Tallahassee Florida. In the early morning hours of January 16, 1978, Ted Bundy entered the sorority house and systematically went room by room looking for victims. Similar to the Halloween character, Michael Myers, Bundy had escaped from prison just days before this killing spree. Armed with a large piece of wood, he bludgeoned, strangled and sexually assaulted two women, killing them before attacking two others. In the space of fifteen to twenty minutes he had stormed the house in what was described as, “a tornado of violence.”[16] After leaving the building, he attacked another girl a few blocks away, dislocating her jaw and leaving her with permanent disabilities. The town of Tallahassee was left reeling. Editor of the local newspaper The Tallahassee Democrat, Malcom Johnson said, “Through all the years of civil rights turmoil we did not have one bloody nose. Now out of the blue we have a homicidal maniac on the loose.”[17] Halloween mirrored Bundy’s melee with seemingly random victims, the violation of a “safe” space (the home becoming the “terrible place”) and the ferocity of the attacks.

Laurie Strode is the quintessential Final Girl. She is studious and dependable, radiating purity. Her friends are almost the exact opposite of her. They are not as constrained by feelings of obligation and responsibility like she is. They are more comfortable in their sexuality and independence. Although it may seem that a girl’s purity is what saved her, Halloween suggests that the inevitable meeting between Laurie and Michael was simply fate, not because she wears dresses and her friends wear pants, and certainly not because they have sex and she doesn’t. The first time she sees Michael is while in class as her teacher discusses fate. Just after Laurie notices him outside the window, her teacher laments, “Fate is immovable like a mountain. It stands where man passes away. Fate never changes.”[19] The implication is that it never mattered if Laurie was the “good girl” or not. She was somehow always destined to cross paths with the killer. Other than simply being in front of the wrong house at the wrong moment, the audience never learns of any other reason why Laurie and Michael would be fated to meet. This nihilistic view that nothing really matters and things just happen is less supernatural than some other slashers and, in a way, truer to real life. Comparable to victims of the Bundy murders, Laurie is similarly the victim of circumstance. The teacher’s statement about fate is also interesting in that it perfectly encapsulates the film’s killer, Michael Myers. A large, stiff, statue of a man made even more stone-like by the pale white mask he wears. He stands “immoveable like a mountain” next to the young girls who are his most common victims.

Some critics have called into question Laurie’s place as a feminist hero, pointing to her purity, domesticity, and submissive nature, especially to male characters, as evidence that she is anything but a feminist. Laurie is a high school student and part time babysitter. This kind of maternal surrogacy, they argue, cannot make her a true symbol of feminism. However, her friend Annie, who is the wilder and more independent of her friends, is a babysitter as well. Regarding her submissiveness, it is true that Laurie is more timid and inexperienced than her comrades. She dresses modestly, is not sexually experienced, and seems painfully shy. In fact, the only time in the film when she seems truly at ease is when interacting with the children she babysits. However, her submissiveness is overstated or patently false. For example, author Kyle Christensen states that Laurie is submissive to her father, “whose only scene is of his shouting orders at Laurie, as she leaves for school.”[20] In fact, using a perfectly conversational tone of voice, he is simply reminding her to drop off a key at a house he is showing later that day. Christensen also points to a scene where Annie coaxes Laurie into taking a hit off a joint. Laurie is clearly inexperienced but not unwilling to try it. When they drive by Annie’s police officer father and stop to say hello, Laurie is visibly nervous that the officer can smell the marijuana. Annie was just as scared of being caught with marijuana. However, she was able to better maintain her composure. Christensen makes the comparison that, “the man of the law [is] becoming the substitute for the “man of God.”[21] It is too great a leap to say a teen doing something illegal and scared of being caught viewed the police officer as some sort of God figure. A timid nature, healthy respect for authority, or simply a respect for elders, does not lessen a woman’s feminist attributes. Despite her timid nature, she is aware of her surroundings, alert to changes that indicate danger is near, and resourceful when tasked with saving her own life.

In one of the most definitive feminist novels of all time, The Feminine Mystique, author Betty Friedan states, “Fulfillment as a woman had only one definition for American women after 1949—the housewife-mother.”[22] Far from the peaceful and serene images of domestic life portrayed in magazines and on television during the 1950s and 1960s, in Halloween the home becomes a battleground for Laurie where she had to use what is available to survive. The role of women in society had changed quite dramatically since the start of second-wave feminism. By its end when the film was released, the role of a woman at home had been redefined. By using instruments of domesticity, such as a knitting needle and wire hanger, as weapons against Michael, Laurie contradicts the notion of a home being a cage. Instead, the home provided what Laurie needed to survive. This is a notion also echoed in the next film, 1984’s A Nightmare on Elm Street.

A Nightmare on Elm Street

Wes Craven’s classic slasher movie, A Nightmare on Elm Street, pits a young girl, Nancy Thompson, and her friends against a child murderer named Freddy Krueger. Many years prior, when a technicality in court leads to Krueger’s release, the parents in town decided that vigilante justice was necessary. They murdered him by burning him alive. Freddie returns to exact revenge on the children of those people who killed him. He does this by slaughtering them in the one place where they cannot be protected, in their dreams.

The idea for the film came to Craven after reading an odd news story about a group of Southeast Asian men who had all died in their sleep. The phenomenon was known as “Nightmare Deaths.” Although factors such as stress, diet and heart issues were theorized, there was no definitive answer as to what caused their deaths. All these men were reported to be healthy before their sudden deaths occurred. Dr. Robert Kirschner, a medical examiner from Cook County, Illinois, and associate professor of pathology at the University of Illinois, investigated the deaths. “These are all healthy men with no previous symptoms; the average age was 33,” he said “The situation is almost always the same. It only occurs in men and it only occurs in their sleep. The report is they cry out and die or are found dead the next morning.”[23] Stories emerged that after these men died, family members found coffee pots and empty cups, indicating that these men were so terrified of falling asleep that they drank coffee in an attempt to stay awake. In total, over 130 men lost their lives in this mysterious manner. This story sat heavy with Craven, and his concept for the film was born.

In early development of the film, Craven imagined the villain, Freddy Krueger, to be a child molester, the worst violent act that he could imagine. However, around the time of the film’s production in 1984, child molestation became front and center in many Americans’ minds due in part to what could be called “the day care scare.” Publications such as Newsweek regularly ran articles about the dangers of day care and its potential detrimental effects on a child’s health and well-being. Day care facilities were portrayed as breeding grounds for neglect and abuse. The mothers that used them, whether by necessity or by choice, were deemed just as culpable as the alleged abusers. As Faludi argued, “The press painted devil’s horns both on mothers who use day care and the day care workers themselves.” Officials within the Reagan administration even spoke out against mothers utilizing day care, saying that to do so was “weakening the moral fiber of the Nation.”[24] Craven did not want to be seen as exploiting those cases, many of which were later found to be baseless. As a result, he backed away from this initial idea.

Krueger is only on screen for a total of less than ten minutes in the movie, but he looms large over the teens he is terrorizing. The mental space he occupies is almost beyond measure. He is inescapable. He can be anything to anyone and he uses his victims’ worst fears to torment and torture them before the inevitable kill. To highlight this, the film strays from the point-of-view (POV) camera work that is typical in slasher films. This adds to the “otherness” of Freddy Krueger. Critics have argued against the POV camera work, saying it is too voyeuristic and leads to a certain sympathy towards the killer rather than the victim. Clover calls it “the assaultive gaze.”[25] A Nightmare on Elm Street does not utilize this technique and therefore gives the viewer more freedom to decide where their interest lies. The film turns the tables even further in the end, when it is a gaze, or rather a lack of one, that ultimately saves Nancy.

Craven’s “Terrible Place” is one of the most unique aspects of the film. Freddy Krueger kills his victims in their dreams. This surreal concept not only allows for some extraordinary death sequences but also has some psychosexual implications worth exploring. Freddy is inside the minds of his victims just as they are “outside” of him. This blurs the line between Freddie and his victims. They become “of” one another. He cannot exist within them without them, and yet he actively works to destroy them. Although Freddy is not motivated to kill because of any sexual rage. He issexual. He torments his female victims with exaggerated sexual comments that are almost comical. The film also juxtaposes horror with sexualized imagery. The most iconic is a scene in which Nancy is taking a bath, with the production camera recording from the foot of the tub looking up at her. In this action Freddy’s hand pops out of the water between her legs. Where other killers are seemingly devoid of sexuality, Freddy is hyper masculine. Interestingly though, his Final Girl and her femininity do not suffer for this. She is not required to give up any part of her femininity, as some critics have argued, to survive his masculinity. Suggesting otherwise would be to falsely assert that the traits Nancy possesses to overcome Freddy are somehow only masculine traits. In fact, the very thing that gave Nancy the jump start on the impending danger, intuition, is a trait mostly commonly assigned to women, that is, “woman’s intuition.”

A Nightmare on Elm Street offers up one of the most grounded, stable, and clever Final Girls of any slasher film. Nancy Thompson is a seemingly popular girl who is by no means a wilting flower. Confident and self-assured, unlike most Final Girls she and her boyfriend Glen are physically close and comfortable with one another. There is no teenage awkwardness between them. Neither one seems dominant within the relationship. They have a rhythm to their union that more closely resembles two adults rather than two teenagers. Although never explicitly addressed, they are a couple who could have engaged in sexual activity. In an early scene, two of their friends, Tina and Rod, run off to have sex in an upstairs bedroom but Nancy and Glen don’t seem particularly interested or embarrassed by the action. Glen confidently leans in for a kiss and a gentle nudge suggesting that they have sex as well, but Nancy rejects him, stating that they are there to support Tina. Tina had been particularly anxious that day after having her first nightmare with Freddy the night before. Although she did not understand what it meant, Tina knew that it was not a normal nightmare and that something was terribly wrong. As a result, she asked her friends to stay with her that night for comfort.

Not surprisingly, Tina becomes Freddy’s first victim, and the killing continues until only Nancy remains. Nancy is immediately open to the idea that Tina’s nightmare could be dangerous. Unlike the others around her, she does not dismiss her friend. After Tina has been killed, Nancy immediately works to protect herself and the others. She reads books on booby traps and self-defense, takes energy pills, and drinks copious amounts of coffee to stay awake. She also maintained communication with her boyfriend and told the adults around her what was happening, even though they didn’t take her concerns seriously. She surmises that the only way to defeat Freddy is to pull him out of her dream and fight him in the real world. Nancy’s plan was for Glen to kill Freddy after she brought him out. But in falling asleep too soon, he fails her. When she asks her police officer father for assistance, he also fails her by not believing her. Kyle Christensen correctly argues, “The men of A Nightmare on Elm Street tend to provide false, unreliable security and leave Nancy vulnerable.”[27]

In the end she can only rely on herself against the homicidal maniac. Breaking from typical slasher films, she ultimately prevails by simply ignoring him. Having faith that she has figured out the secret, she grabs Freddy in her dream and then wakes up, pulling him into the real world with her, thus making him vulnerable. Prior to this, Nancy had set up booby traps in her home to disorient Freddy and create distance between herself and him. She weaponized her home making it her battleground. The familiarity of her home is used to her advantage. When Freddy is about to attack her, she turns her back to him and proclaims, “I take back every bit of energy I gave you.”[28] By pulling Freddy out of her subconscious, she strips from him all that makes him masculine until, confused and scared, he dissipates into nothingness. Asserting that “Nancy’s turning her back on Freddy can be seen as controlling the gaze, in that she has the power to either accept or reject it, rather than simply being its object,” Carol Clover suggests that she does not have to relinquish any of her femininity in order to prevail.[29]

Carol Clover argues that Final Girls are not “fully feminine,”[30] at least not when compared to their female friends. Their mannerisms, clothing, and even their names are all bordering on the masculine side. Nancy completely challenges this argument. Nancy’s rejection of her boyfriend’s sexual advances was due to genuine concern and compassion for her friend rather than naivety, inexperience, or prudishness. Her clothing was of the same style and aesthetic as her sociable friend, Tina. In addition, unlike other Final Girls with names like “Stevie” or “Joey,” the name “Nancy” is not used in any unisex or gender-neutral way. It is, in fact, considered so extremely feminine that it can be used in a derogatory way towards a man who is viewed as effeminate.

Clover also argues that even though the male-to-female death ratio is relatively the same in these films, male deaths are shown very differently than female deaths. She asserts that male deaths are far more impersonal, often off screen and less graphic. She writes, “He is dispatched and the camera moves on.”[31] A Nightmare on Elm Street, however, does not follow this formula. Of the four people who die in the film, the bloodiest and most iconic death is Nancy’s boyfriend, Glen. Although trying to stay awake to help Nancy capture Freddy, Glen succumbs to his exhaustion later that evening. With terrified screams, he is sucked into his bed only to return in what can only be described as an upside-down blood waterfall. In the film, Rod says to Tina, “Guys can have nightmares too, ya know. Ya ain’t got a corner on the market or somethin’.”[32] Freddy Krueger was an equal opportunity killer, and fans, both male and female, were along for the ride. Feminism had split into two vastly different schools of thought at this time. Where a person fell into those ideals determined their acceptance of slasher films.

Feminisms Splits

During the small window of time in which slasher films were at their height, society was in the middle of a seismic shift. Second-wave feminism began around 1960 and was coming to a close by 1980. The movement fractured into two different camps: the anti-pornography feminists (APF) and sex-positive feminists (SPF). APFs were firm believers that all forms of pornography were harmful to women because they glorified male dominance over women. They were vehemently opposed to sadomasochism and other violent sexual acts, arguing that these movies promoted violence against women, even if these acts were consensual. APFs also opposed prostitution, whether legal or not, for similar reasons. SPFs took a far more liberal approach to these topics. They felt that the anti-pornography feminists were exercising their own form of sexual repression and oppression against women. For SPFs, as long as there was clear consent, a woman should be free to engage in whatever sexual activity she wanted to without shame or guilt. This internal debate between the two groups was known as the feminist sex wars, and effectively signaled the end of second-wave feminism.

Slasher films and viewership of them can be regarded in similar terms, specifically female viewership of them. While it is a fact that the majority of the horror audience is male, there are passionate female fans who genuinely love the genre. Unfortunately, these women are rarely taken into consideration during any horror discussion. Author Isabel Pinedo notes that the discourse surrounding horror films is “peopled with sadistic male viewers who enjoy reviling images and principled feminists who abhor the same. It leaves no room for the pleasure of female viewers, particularly feminists, except as masochists or sex traitors.”[33] However, if the second wave of feminisms’ ultimate goal was to allow a woman complete and total control of her own body, then what she consumes with her eyes and feels in her heart should be no exception regardless of how bloody or violent the content. Women who watch horror movies don’t necessarily do so because they are masochists or because they are, in some way, ashamed of or apologetic for being a woman. In many cases, quite the opposite is true. Seeing a woman, particularly a young woman whom society may view as being dependent ultimately becoming independent, is empowering. As a result of her experience, the Final Girl may be less trusting or more easily scared. However, she would also know that when backed into a corner, she could save herself because she had already done so. In the slasher film a teenage girl, through her experience of danger and trauma, becomes a woman in the end. The films are, of course, distorted and melodramatic portrayals. However, they speak to female audiences about their shared emotions of danger, fear, vulnerability, disappointment, and, in the case of the Final Girls, triumph.

Conclusion

When slasher films premiered, second-wave feminism was just ending and a new era was dawning in the United States. It was an era bringing with it neoliberalism, the continuation of the Cold War and a “greed is good” mentality. America had just ended its official involvement in the Vietnam War. Second-wave feminism had challenged the traditional view of a woman’s role in the home and in society. While feminists argued about what constituted real feminism, slasher movies did not make the docket. It was only later that a few feminist authors took the time to examine these films and interpret their deeper meanings. While hard numbers regarding female viewership of horror films is scant, people within the horror industry are beginning to recognize the female viewer. When executives for the on-demand streaming service FEARnet were preparing to launch their service, company President Diane Robina said, “When we launched the network, we went out and did focus groups and it was the women in the room who really wanted a horror channel more than the guys did.”[34]

Horror films today are still responding to audience anxieties, producing visually graphic works of biting social commentary, sometimes referred to as “backlash horror.” Eli Roth’s 2005 film, Hostel, was a particularly disturbing response to the torture tactics used during President Bush’s “War on Terror.” Jordan Peele’s 2017 hit, Get Out, and his 2019 follow up, Us, addressed race and class issues. Additionally, more horror films are being produced today with female leads such as 2018’s Greta and 2019’s Ma. Slasher films were certainly not the only type of horror film produced during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but they had the most impact on the genre at the time. They continue to thrive today at horror conventions, network television programming especially during Halloween, and in the countless sequels, prequels, and remakes that have been made since their original inceptions.

During a 2016 discussion at the New York Film Academy, John Carpenter said, “Horror has been with cinema since the very beginning. It grew up part and parcel with the image, with cinema. And it will always be with us. It’s one of the most popular genres of all time. And it’s an all-purpose genre because it keeps changing. Every culture, every few years, it morphs, it changes into something else. It brings the sensibilities of the age in which it’s made and that’s what’s so fabulous.”[35] The classic slashers are no exception. Film critics Siskel and Ebert were incorrect when they asserted, “These films hate women,” and labeled them “against the women’s movement.”[36] The films themselves were not anti-woman, but rather reflected societal issues in sensational and excessive ways. While some women may dislike horror films for any number of reasons, consideration must also be paid to women who choose to watch and enjoy the films. Just as the SPFs of this time argued for the sexual freedom of consenting adult women, so too should “horror-positive” feminists advocate for their viewing freedom without being labeled sex-traitors. Slasher films have heroic female characters who challenge the traditional view of what a woman is or should be. They also portray fears and anxieties held by people of both genders in society and culture.

Between 1995 and 2019, the horror industry generated revenues of nearly eleven billion dollars in North America alone.[37] Horror films brought in more revenue than the romantic comedy genre. Adolescent males may be “the slasher film’s implied audience,”[38] but they are certainly not its only audience. Young girls, married women over thirty-five, single women and, of course, “ladies” all watch horror films. These women watch slasher movies not only because they are an adrenaline rush, but are also an empowering choice. When a woman decides to view horror films, “she is choosing fear and controlling it.”[39] The films tell a story that audiences want to hear, in a terrifying way they want to see. Whether conscious of it or not, slasher films are a safe way for fans to grapple with the hot issues of the day. When you look beyond the blood and the breasts in slasher movies, you are left with a plot in which the last “man” standing is the Final Girl. Not only is she worth a meaningful discussion, but so too is the female audience watching her.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

A Nightmare on Elm Street. Directed by Wes Craven. New Line Cinema, 1984. Accessed March 12, 2019. iTunes.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984).” IMDb. Accessed March 31, 2019. https://pro.imdb.com/title/tt0087800?rf=cons_tt_contact&ref_=cons_tt_contact.

Carpenter, John. Discussion with Filmmaker John Carpenter. October 13, 2016. Accessed April 14, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EsBlObL83E0.

Halloween. Directed by John Carpenter. Compass International Pictures, 1978. Accessed April 14, 2019. iTunes.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Directed by Tobe Hooper. Bryanston Distributing, 1974. Accessed April 14, 2019. iTunes.

Secondary Sources

“1973 Oil Crisis.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Last edited September 10, 2019. Accessed February 2, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1973_oil_crisis.

Berardinelli, James. “Nightmare on Elm Street, A.” Reelviews Movie Reviews. http://www. reelviews.net/reelviews/nightmare-on-elm-street-a.

Christensen, Kyle. “The Final Girl versus Wes Craven’s “A Nightmare on Elm Street”: Proposing a Stronger Model of Feminism in Slasher Horror Cinema.” Studies in Popular Culture 34, no. 1 (Fall 2011): 23-47. Accessed February 2, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23416349.

Clover, Carol J. Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Eli Roth’s History of Horror. Season 1, episode 2, “Slashers Part 1.” Produced by Eli Roth and Joseph Freed. Aired October 22, 2018 on AMC.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women. London: Chatto & Windus, 1992.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013. Kindle.

Garris, Mick. “Tobe Hooper.” In Post Mortem with Mick Garris. Directed by Perry Martin. September 1, 2014.

Kael, Pauline. “Halloween (1978).” New Yorker, February 19, 1979. Accessed May 7, 2019. https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/2017/10/17/halloween-1979-review-by-pauline-kael.

Kendrick, James. “Razors in the Dreamscape: Revisiting “A Nightmare on Elm Street”.” Film Criticism 33, no. 3 (Spring 2009): 17-33. Accessed April 13, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44019225.

Philbin, Tom, and Michael Philbin. The Killer Book of Serial Killers: Incredible Stories, Facts, and Trivia from the World of Serial Killers. Naperville, IL: Source Books, 2009.

Pinedo, Isabel Cristina. Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1997.

Shaulova, Esther, Lodovica Biagi, and Ziyan Zhang. “Statista – The Statistics Portal for Market Data, Market Research and Market Studies.” Statista – The Statistics Portal for Market Data, Market Research and Market Studies. 2019. Accessed April 14, 2019.https:.//www.statista.com/statistics/188658/movie-genres-in-north-america-by-box-office-revenue-since-1995.

Siskel, Gene, and Roger Ebert. “The Stinkers of 1984.” At the Movies. WGN-TV Studios. July 17, 2015. Accessed February 16, 2019.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fgigm0dY8IM.

Siskel, Gene, and Roger Ebert. “Women in Danger.” Sneak Previews. Public Broadcasting Station. October 24, 1980. Television.

Spines, Christine. “Chicks Dig Scary Movies.” Entertainment Weekly, July 24, 2009. Accessed April 21, 2019. https://ew.com/article/2009/07/24/chicks-dig-scary-movies.

Vela, Natalia. “Date a Girl Who Watches Horror Movies.” Thought Catalog. April 3, 2018. Accessed April 21, 2019. https://thoughtcatalog.com/natalia-vela/2018/04/date-a-girl-who-watches-horror-movies.