By: Ariel Cowger

We climbed mountains, we hid under rivers. We captured prisoners. We carried ammunition. We trained ourselves to use weapons. We guided the soldiers when they wanted to attack the American base at Binh Duc. We were the guides, we were the spies. Don’t you see? Ours was a citizens’ war. We were the women fighters.

-Lady Borton, After Sorrow: An American among the Vietnamese.

Introduction

In 1960, an outpost in Ban Long, South Vietnam was attacked by Viet Minh soldiers.[1] Explosions lit the area as smoke and bright lights hid an unknown number of armed Viet Minh attackers who encircled the outpost before retreating for the night. The following morning civilians in the area warned the occupying soldiers of the numerous Viet Minh they saw the night before and of the deadly firepower they carried with them. Later that night the attack resumed as the Viet Minh increased their assaults. It seemed that even more fighters than the previous night were assaulting the outpost, running from place to place amidst the smoke and light surrounding the post. Fearing for their lives, the South Vietnamese soldiers fled the post, leaving behind weapons and other supplies. In actuality, there were no Viet Minh soldiers during either “attack”. Frustrated with the local government’s policies and treatment, a small group of women and a few remaining men who hadn’t been called north to join the fighting built fake guns out of wood and water-palm stems. They also used homemade explosives along with smoke and light to silhouette themselves as they “attacked” the post, making it impossible to tell that their offensive was a complete fake. They encouraged the civilians to lie about the presence of the Viet Minh, their numbers, and military strength. After the army soldiers fled, the group of local women and men seized the weapons and supplies left behind and armed themselves.[2] This is just one story of many that tells of women stepping out of the traditional domestic role to organize missions and to protect themselves, their families, and their villages. During the French War as well as the American War in Vietnam,[3] women were involved not only in a support capacity but also militarily and combatively through their roles as guerrilla fighters, guards, transportation guides, and operators of anti-aircraft guns.

When the Vietnam War is discussed in scholarship and fiction, it is most often looked at through the lenses of politics, its unpopularity, and American male G.I.’s. The familiar American narrative, found in memoirs, movies, and some scholarship, often ignores the roles played by women, except as bar-girls and prostitutes. One example of Vietnamese women being portrayed as sexual and deviant can be found in Stanley Kubrick’s film, Full Metal Jacket. There is a famous scene where two American G.I. characters, Joker and Rafterman, are approached by a young Vietnamese prostitute who coaxes them to buy her services for a time. Repeating the phrases, “me so horny” and “me love you long time,” this woman provides the male audience with an accepted stereotype as well as a bit of comic relief as the men onscreen bargain for a cheaper price.[4] Since the movie’s release in 1987, this scene and this prostitute’s dialogue have turned into a catchphrase that represents Asian women and their purpose of serving in male fantasies. Perhaps this narrative is so popular because so many works on Vietnam have been written by men or published in fields dominated by men, such as the mass media and journalism, particularly war journalism.[5] While some Vietnamese women were bar-girls and prostitutes, many women were active combatants in the war, participating in military units as well as taking up arms in a civilian capacity. They also acted as spies, scouts, logistical support personnel, and recruiters. In other words, they took on a variety of roles. To appreciate women’s contributions and understand their place in the wars in Vietnam we must consider all of their roles.[6]

A number of scholars have written on the subject of gender and women in Vietnam, including periods before, during, and directly after the war. A number of secondary sources were compiled and analyzed in order to frame an argument and build upon their research. In particular, Susan Jeffords, Lady Borton, Heather Stur, Sandra Taylor, and Karen Turner offer unique insights into the gender dynamics of the period, American and Vietnamese cultures, and Vietnamese women’s roles and experiences during the war. This contribution to the already established body of scholarship will argue that women not only resisted gender norms, but also maintained traditional gendered beliefs, such as the concepts of femininity and motherhood. Women played into and contradicted gender norms, which allowed them to be manipulated by the North Vietnamese government as well as underestimated by the American military.

Women confirmed gender norms as well as contradicted them through their diverse combat and support roles. To understand the significance of the roles that Vietnamese women played during the American War and how these roles reflected American and Vietnamese gender norms and stereotypes, one must first understand the gender dynamics of the period. Although American and Vietnamese cultures shared similarities during this period, such as a patriarchal society placing women in a domestic role, these two cultures also had unique aspects. These included America’s emphasis on masculine strength and Vietnam’s tradition of warrior women dating back to 40 CE with the Trung Sisters.[7] American gender culture during this time was a continuation of the Cold War gender culture which emphasized male masculinity and female domesticity and chastity. Since women were viewed as weak and frail, Vietnamese women were able to take advantage of American men’s perceptions to gain the upper hand, not only in combat situations, but also when engaged in espionage. Alternatively, Vietnamese culture, while similarly emphasizing patriarchal attitudes such as female submission and other characteristics of Confucianism, also encouraged women’s participation in the war.[8] The North Vietnamese government promoted equality between men and women, and used women’s desire for that freedom, along with other motivations, in order to exploit them during the war. With American and Vietnamese men’s views on women as submissive or weak, the North Vietnamese government was able to use women to further their agenda by surprising American expectations and shaming Vietnamese men into working harder. These complexities and contradictions in the gender expectations of two cultures—American and Vietnamese—allowed Vietnamese women to be ignored and underestimated by the American military and exploited by the North Vietnamese government.

American Gender Culture and Stereotypes

In the years leading up to the American War in Vietnam, the Cold War gender culture was still in effect. This culture stressed a middle-class domesticity, heterosexual couplings, and contained sexuality. The ideal woman for men following this system of thinking was someone who conveyed a wholesome and chaste nature.[9] Since the American War came at a time when American women were questioning their own sense of family and gender roles,[10] men invested in the status quo were more desperate than ever to continue perpetuating traditional gender norms.

Women were viewed as being weaker than men and something to be protected. If a woman did not fit into men’s idealized gender roles then they were seen as “other”. Historian Heather Stur notes that during the American War, American men categorized women into three separate categories: “Dragon Lady,” “Girl Next Door” and sexual object.[11] Whether a woman was a dangerous threat, something to be protected, or something to be dominated were decisions men made based on their view of how women acted according to their stereotypes of women. A common practice for women who didn’t fit the mold was to demonize them. The American military did this effectively to Vietnamese women, especially bar-girls and prostitutes, but not limited to those roles. The “Vagina Dentata” and “Incurable Venereal Disease” myths serve as examples of the way in which soldier gossip played a role in demonizing women. These myths were stories that were told by American soldiers about the terrifying ways in which Vietnamese women attempted to maim, kill, or in some way injure American G.I.s.[12] The “Vagina Dentata” myth, as it pertains to the American War, tells of how Vietnamese women (usually prostitutes) would insert sharp objects such as razor blades or broken Coca Cola bottles into their vagina before having intercourse with an American G.I.. According to the men, this action was done intentionally by the woman who would then seduce American men in an attempt to maim or kill them through intercourse. Similarly, the “Incurable Venereal Disease” myth tells that Vietnamese women, in an attempt at biological warfare, would infect American men with incurable venereal diseases resulting in the man being sent to an undisclosed island where all other infected men were hidden away by the American government, never to be seen or heard from again. In an exploration of this myth, Monte Gulzow and Carol Mitchell interviewed one woman and fifty-two men, “most of whom were ex-servicemen and thirty-five of whom had served in Vietnam.”[13] Based on their interviews, they concluded that these legends probably originated as a result of the military’s attempt to keep American men from fraternizing with Vietnamese women. This effort would prove to be unsuccessful despite the fabricated risks. Whether or not these legends are true, the rumors themselves serve as evidence of the caution and mistrust towards Vietnamese women. These myths are a direct threat to men’s masculinity. In the case of the “Vagina Dentata” legend, the penis is the ultimate symbol of masculinity, and any damage to it serves to emasculate a man. This legend allows men to see Vietnamese women as a literal threat to their masculinity and, therefore, a threat of the highest form. It should be noted that although these Vietnamese women were considered a threat to men’s masculinity, they were not deemed a legitimate threat to the American military’s operations in Vietnam.

The fear of emasculation has been most effectively exploited by the military, who uses gendered vocabulary such as “pussy”, “sissy”, and “ladies” during men’s training.[14] This fear of becoming like a woman allows for women to become the enemy, which the military plays on and perpetuates through training and the use of gendered terms to humiliate men. Not only are these gendered terms able to humiliate American men, but their use against the enemy allows Americans to dehumanize the Vietnamese by feminizing them. The American military also emphasizes masculine strength, encouraging the idea that women must be protected. With a lack of American women in Vietnam, men’s idealized concepts of women were placed on Vietnamese women, who then became representatives of an American-style femininity.[15] During the war, Vietnamese women would be able to play upon these stereotypes in order to take advantage of American men.

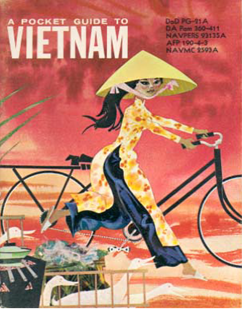

One can see American gender norms and stereotypes at work through the booklets and literature produced by and for the military during the war. Not only is American gender culture present in these publications, but American perceptions of Vietnamese gender norms as well. A Pocket Guide to Vietnam was a booklet written for American soldiers in order to prepare them for living in Vietnam.[16] The guide includes brief information on Vietnam’s people, history, government and customs. The cover of this booklet features a young woman wearing a traditional ao dai, which suggests how Americans viewed Vietnam as a country.[17] By having a woman wearing such a conservative outfit associated with beauty and femininity on the cover, it is clear that Americans felt that this was an accurate representation of Vietnam as a whole: peaceful, beautiful, and weak. This guide, as well as others, discusses women and their place in the home, noting that women were subordinate to men. However, they also claim that women had tremendous influence over their husbands’ opinions and actions.[18] These comments demonstrate the Americans’ inability to acknowledge women’s power outside of the home, and that their roles may not have fit into idealized norms. Because Vietnamese men were influenced by their wives, Americans began to see those men as being un-masculine and, therefore, weak. Vietnamese men were also seen as effeminate and weak due to their small stature, delicate features, cultural same-sex hand holding, and cultural male kissing. By allowing themselves to feminize Vietnamese men, American men could dehumanize them, leaving themselves open to exploitation by the men and women they underestimated.

The Area Handbook for South Vietnam, a booklet created for the U.S. military, includes information regarding the social, political, and economic status of Vietnam, as well as a section on national security. The handbook notes that “some women actually join the fighting,” but their roles in the conflict aren’t specified, nor do they seem like an actual threat to the American military. The only motivation listed for Vietnamese women who join the war is that of following their husbands into battle.[20] Americans could not understand the notion that women would seek out combat unless in service to their husbands. Almost a million women fought in northern guerrilla and militia forces during the war, with 40% of the guerrilla forces in the South being made up by women.[21] Despite the number of women in roles that directly contradicted American gender norms and expectations, American men continued to underestimate women and their positions. Information exists regarding bounties that were placed on dangerous women who eluded capture during the war. This proves that the American military knew that Vietnamese women were capable of being aggressive enemies. Yet no effort was put into making soldiers aware that women were a threat as fighters, spies, or messengers. Another handbook disseminated by the U.S. Navy urged soldiers to understand the cultural differences between the American and Vietnamese people, but only applied that knowledge to interacting in a sexual or intimate manner with Vietnamese women and what not to do in public such as holding hands. There was no information in this document about women’s roles in combat situations, only how to correctly date a Vietnamese woman.[22] This blatant show of underestimating women comes from American men’s idealized sense of feminine weakness and the gentle innocence of women found in American gender culture.

Vietnamese Gender Culture

Vietnamese gender roles can be linked back to the Chinese occupation of the country beginning in 40 CE where Confucian virtues were introduced that still held sway in Vietnam during (and after) the war. One of the most famous pieces of Vietnamese literature is a poem by Luc Van Tien, which tells the love story of a young male scholar and a virtuous girl. This story upholds Confucian virtues of loyalty, filial devotion, and female chastity.[23] Its continued popularity shows how traditional morals appealed to the people of Vietnam.[24]

During this time, and for a period of time after the war, Vietnamese women’s main value in society rested in their ability to perform domestic roles such as bearing children and being a “good” wife to their husbands. Women were expected to be subservient to their husbands and to care for them in the home by performing tasks such as cooking dinner, housecleaning, etc. Marriage was important in the eyes of Vietnamese society. Women were expected to be skilled enough to acquire and keep a husband. Even if husbands were abusive toward their wives, women rarely left them for fear of the community’s judgement of them. Similarly, women’s virginity and her body’s worth were determined by the value it had to men, specifically their future husbands. In the event of rape, the assault was not considered degrading to the woman personally, but instead devalued her worth as a potential wife and child-bearer. [25]

Motherhood was of particular importance to women in Vietnam. With societal pressure on women to bear children, motherhood became a characteristic for which they yearned and fought. Female veterans after the war argued that they had earned the right to be mothers after their sacrifices. They used this argument to manipulate their own culture’s gender norms to gain personal goals that would otherwise have seen them ostracized from society. For example, adopting children, having children out of wedlock, and having more than the two child limit that the government enforced, were ways that female veterans were able to manipulate the sanctity of motherhood in order to gain what they considered the ultimate achievement of having children.[26] These manipulations provide insight into how women maintained gender norms through their pursuit of motherhood. These actions serve as an example of the ways in which women exploited the government by using upheld norms to achieve motherhood in more unorthodox and less socially acceptable ways.

Prior to and during the war, women living in rural areas were heavily involved in farming alongside their husbands. Women’s work included fertilizing, transplanting, weeding, milling rice, and storing and preserving food. They were also involved in livestock breeding, harvesting, and plowing, which were jobs that often belonged to men.[27] What would become one of their most valuable roles, however, was as a seller in marketplaces. The market was a perfect place to exchange information. Women used this network to disseminate propaganda and information for the Viet Cong.[28] Uprisings that took place in the 1940s and 1960s during the French and American Wars relied on women at the market to spread the word and organize rebellions. Despite this, the American military continued to underestimate women’s abilities to assist the Viet Cong and their importance to the war. Women involved in the American War would rely heavily on the experience of the older generation of women who fought against the French for tactics and skills to use against the Americans.[29] It was because of American men’s perpetuation of gender roles and the perceived weakness of Vietnamese men and women that Vietnamese women were able to take advantage of American men in order to support North Vietnam. They became an invaluable asset to their comrades.

Vietnamese women serving in support and combat roles during times of war was nothing new. Stories of the tradition of warrior women date back to 40 CE with the Trung sisters and continued throughout Vietnam’s history with other exceptional warrior women such as Phung Thi Chinh and Lady Trieu Thi Trinh.[30] Women were raised on stories of these warriors and their heroics. Thus, it should come as no surprise that women were eager to participate in battle in order to live up to their ancestors who fought before them.

One of the most influential government bodies in Vietnam during the war (and arguably after) was the Women’s Association. Founded in 1930, the main function of the Women’s Association was to act as intermediary between the North Vietnam Communist Party, specifically the National Liberation Front (NLF), and the people, particularly women.[31] While the Women’s Association encouraged women to participate in the war and worked to educate and mobilize them, it did so at the behest of the North Vietnamese government. State policies rather than women’s issues were the primary focus of the Women’s Association.[32] By manipulating women’s desires to unify with other women, the NLF was able to mobilize women for the war effort and use them effectively against their American enemies. One example of this came in 1964 via a campaign by the Women’s Association called the “Three Responsibility Movement” (also called the “Three Security Movement”). This campaign called on women to ensure that production continued during the war, encouraged their fighting service, urged them to continue to care for their families, and called on them to contribute to building the north while reinforcing the south.[33] Rather than promoting gender equality, the ultimate goal of this and other campaigns led by the Woman’s Association was to use women to further the aims of the North Vietnamese government.

The liberation of women in Vietnam has been cited as one of the motivations for their participation in both the French and American Wars. Ho Chi Minh, leader of the Communist Party in North Vietnam, argued for women’s liberation during the French occupation, and continued to do so during the American War. In fact, the 1946 North Vietnamese Constitution included economic and political equality for women and women’s suffrage.[34] However, the law did not change cultural norms and expectations, resulting in almost no change in women’s status.[35] Some men blamed women for their lack of progress, claiming that they were “too willing to serve men” to break out of their traditional roles. Despite women’s “equality” and their encouragement to join the war, some Vietnamese men still retained their traditional expectations of women as gentle nurturers and supporters of male soldiers. In one woman’s official “curriculum vitae” (a record of life and service that all people carried), party officials commented that she was “brave and diligent, but hot tempered and quarrelsome”, and that “although she’s performed several missions, she still doesn’t understand her part very well.”[36] It is clear that male officials labeled women differently. Being a successful soldier and leader would garner praise for a man, but in this case a woman was labeled as being somewhat disobedient and confrontational. The comment that she “doesn’t understand her part very well” suggests that women were expected to mainly participate in support roles. If they did rise up through the ranks they should do so silently and without drawing attention to themselves. More importantly, women should not draw attention away from male leaders and their achievements.

Interactions Between Vietnamese Men And Women

Memoirs and interviews have given historians insight into how Vietnamese men and women interacted with one another during the American War. There are multiple contradictions found in reference to men and women’s relationships. Men both respected and criticized women during wartime. Vietnamese men respected women’s intelligence and determination in the field but also considered them as pretty distractions, objectifying them so that their main value was in their looks.[37]

There has been a reported lack of sexual relations in the field during the war. It has been suggested that having a shared enemy and workload, combined with the harsh conditions in the field, allowed for a sort of gender neutrality where sex was less important than getting the needed work done.[38] This is not to say, of course, that sex, both consensual and not, didn’t occur. Sexual assault is notoriously underreported in any society, and rape or sexual assault were not often topics of discussion by Vietnamese veterans. Therefore, it is possible that these acts occurred but went unreported. Some Vietnamese women have hinted that women became vulnerable in the field only when they stepped outside of the sphere in which individuals depended on one another, such as when they interacted with officers or those in command.[39] The consensus seems to be that there were not many problems between men and women in the field. Perhaps a less hierarchical structure allowed for a more equal interaction between men and women, fostering less sexist behavior. It is unclear whether this behavior lasted throughout the war.

Expectations of women, and men’s feelings towards them, were quite complex and contradictory. While they respected women’s ingenuity, intelligence, and fortitude in the field, men also encouraged women to preserve their femininity and cultural norms during the war as well.[40] Even accomplished warrior women like Nguyen Thi Dinh were expected to keep their feminine traits. While she was able to organize missions and small rebellions, sometimes while imprisoned, Nguyen Thi Dinh was lauded as being modest and feminine. Here was a woman engaging in espionage and combat, who later became the first female general of the Vietnam People’s Army. Yet she was most often praised, not because of her military prowess, but rather due to her ability to balance martial and feminine skills.[41]

She was lauded as being modest and feminine despite being able to organize missions and small rebellions, sometimes while imprisoned. Here was a woman engaging in espionage and combat, later becoming the first female general of the Vietnam People’s Army, who was most often praised because of her ability to balance martial and feminine skills. These praises completely disregarded her capabilities as a military prowess.

It is because she retained her femininity through battle that men were willing to praise her efforts as a soldier. It is clear that women were often more respected by their male comrades due to their ability to be objectified by their looks and feminine actions rather than the more masculine roles that they adopted. Contrary to men’s expectations of women’s femininity, some men expressed appreciation of women’s efforts during the war. In interviews conducted after the war many male veterans conveyed their gratitude toward women and their valuable participation.[42] These interviews were held in groups that included both male and female veterans. Therefore, it is difficult to know whether these men’s comments reflect their true feelings or were said to appease the women among them. There were some men who blatantly did not accept women into their ranks during the war. Nguyen Thi Dinh admits in her memoir that she and other women had to cope with the contempt of their male comrades. One woman agent in a prominent position disguised herself as a man to “deceive the enemy and also to put the minds of the men in my cell at ease.”[43] Her reluctance to expose her true gender shows that even male comrades had certain expectations of women and their roles. It is clear that, despite women’s diverse support and combat roles during the war, in the majority of cases, gender norms remained the same during the war as well as after.

By 1966, thousands of women were in the field. Yet they are absent from military reports. Nevertheless, those same reports show that work was getting done more efficiently and in a more organized manner than before.[44] Two conclusions can be made from this information: women provided enormous assistance to the war effort, and men were highly influenced by women’s participation. Praise of women’s achievements during the war gave the North Vietnamese government the opportunity to enlist the help of more women while at the same time shaming and motivating Vietnamese men into applying more effort.[45] In a Confucian society, men are considered dominant and are the head of their families. Having women in equal or leadership roles had the ability to shame men. These men disliked the position in which women fighters put them. By introducing women into the field alongside men, those men felt the need to push themselves harder in order to retain their dominant positions. This contradiction of traditional gender norms was one way that the NLF was able to use women to motivate Vietnamese men to work harder and support the northern cause to the best of their abilities. After all, if women were willing to fight and make sacrifices, then men would have been more determined to perform the roles in which they were needed.

Challenging Gender Norms During Wartime

During the American War, Vietnamese women found themselves fully immersed in the conflict. Whether they had family and friends involved, or were personally involved, the war impacted their lives substantially. Vietnamese women’s participation in the war was all-encompassing. They contributed politically, combatively, and productively.[46] This section emphasizes the roles that contradicted American expectations and, to an extent, Vietnamese expectations as well. For example, roles such as those in the nursing or medical field are not mentioned. However, this should not be seen as an indication that these roles and others like them were any less important during the war.

It is estimated that almost a million women participated in North Vietnam’s guerrilla and militia forces, with approximately 140,000 women operating in the South to support the North as propagandists and spies.[47] Many women of the North joined the Volunteer Youth Corps, an organization made up of young men and women volunteers who were primarily responsible for work on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, although they were given other duties.[48] Some girls were as young as thirteen years old, but the majority of women who joined were between the ages of seventeen and twenty . Work along the Trail—the main route for moving supplies and soldiers between North and South Vietnam—included repairing damage done by American bombs, operating anti-aircraft guns, and guiding men and supplies through the network of roads that made up the Trail. These youth, among which 70% were female, maintained over one thousand miles of road, built six airstrips, shot down dozens of planes, and transported tens of thousands of weapons and food.[49] Women’s participation in these ways contradicted the idea that war was men’s work.

More often than not, Vietnamese women were given dangerous tasks in the field. Using their smaller stature and unassuming presence, women planted mines and booby traps to injure or kill Americans.[50] They also proved efficient at shooting down enemy aircraft. Some women even boasted at having better aim than most, if not all, of the men. These women were openly praised by officials for their marksmanship abilities as well as their fierce determination in battle.[51] By publicly acknowledging and commending women participants, the North Vietnamese government was able to create conflict in regards to traditional roles of men and women, manipulating not only the women who continued to work for the praise of their leaders, but also the men who became more determined than women in order to maintain their dominant roles.

Women also proved invaluable to the Viet Cong in the realm of logistics and the transportation of goods and troops. While the Ho Chi Minh Trail was used to transport large groups of soldiers and supplies, women took part in transporting troops and arms on a more localized level as well. Instead of clearing the way between North and South Vietnam, some troop movement required smaller escorts within the country to which women lent themselves.[52] Women also provided and smuggled food to individual soldiers and units. In other words, even those women who were not involved in combat played a crucial role by using their skills and abilities to feed, care for, and at times, hide Viet Cong soldiers.[53]

Vietnamese women employed their feminine roles as mothers and wives to motivate and encourage their husbands and sons to join the war.[54] According to U.S. research during the war,[55] women that motivated their husbands and sons were more of a threat to the American military than in their roles in combat and support. American gender norms played a crucial role because the American military knew what women effectively did for the war. Yet it still didn’t consider women a huge threat to American men. This particular military research includes a captured document citing thirty missions and plans that the Vietnamese were prepared to enact, including increased guerrilla movement and fighting at the Front. The U.S. military’s summary of this document, however, is most concerned with the mention of women motivating men to fight rather than women shooting down their planes, planting mines, or engaging in espionage. American leaders were not ignorant of women’s combat and intelligence roles during the war. Under the guidance of American gender expectations, the American military severely underestimated and ignored women because their norms considered women as submissive and weak. Despite evidence of women’s capabilities, American sexism won out. Vietnamese women were overlooked and underestimated. Not only did women encourage the men they knew, but unknowingly encouraged men in the field as well. Women who shared space and responsibilities with men in the field found themselves boosting the morale of those men through their determination and general feminine presence.[56] This, of course, contradicts the idea of women being exploited into shaming men and manipulating them to work harder, suggesting that women’s presence in the war is a complex and multifaceted issue in which women both played into and against gender norms.

Women expressed the biggest contradiction of all when they maintained the dual roles of mother and warrior. Motherhood fits into both American and Vietnamese gender norms and is closely linked with the feminine and domestic expectations of women in both cultures. The idea of a mother wielding a weapon in battle directly challenges the notion of a nurturing woman. Women’s complexity and agency is, therefore, expressed through their roles as mothers who, while nurturing, were also capable of killing and handling deadly weapons with competence. This served as another way for the northern government to exploit women in ways that Americans would not expect, such as organizing missions or engaging in espionage. Despite a tradition of warrior women, Vietnamese men could also be manipulated through women’s dual roles of mother and warrior. A Vietnamese mother was expected to care for her family and home. Her participation in the war allowed the North Vietnamese government to shame and manipulate Vietnamese men into working harder than their female comrades.

Arguably the most important roles Vietnamese women played during the war was disseminating propaganda, passing along messages, and partaking in espionage. The Viet Cong frequently used women as spies to infiltrate American and South Vietnamese military bases to acquire information on troop movements, officers’ maps, and supplies.[57] Similarly, bar girls and prostitutes were encouraged to spy on the men who paid for their services.[58] Flirtation, seduction, and general femininity were tactics that women used to gain information from Americans and their South Vietnamese allies. This is an example of how women conformed to gender norms and expectations in order to gain the upper hand. This also serves as a model of the ways in which the North Vietnamese government used women and their femininity to further their agenda. Because women were underestimated due to their sex, they were able to smuggle out information to the Viet Cong. Often women did not smuggle physical information. Rather they memorized the information to be passed on to their leaders. The U.S. military never considered that Vietnamese women might be smuggling secrets in this way because their gendered views led them to believe that women were not capable of such complex acts of espionage.[59]

Another example of the North Vietnamese government using women and American expectations to further their agenda is evident through their use of Madame Nguyen Thi Binh during the Paris Peace Conference. Mme. Binh was chosen by Ho Chi Minh to head the NLF delegation as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1968-1973.[60] She was the only woman to sign the treaty in 1973, placing her as an equal to the American Secretary of State and Commander in Chiefs from Laos and Cambodia.[61] Mme. Binh drew attention to herself and, ultimately, the cause she was there to represent. Commonly seen wearing a traditional ao dai, she used clothing and femininity to gain attention and world sympathy for the NLF’s Communist cause by playing upon American sensibilities and gender expectations.[62] Ho Chi Minh purposefully chose Mme. Binh as his representative because he knew the effect she would have, not only on the men present at the conference, but also the men of the media and press corps.[63] By exploiting Mme. Binh’s looks, presence, and role in the conference, Ho Chi Minh was able to gain international attention to the Communist cause by drawing sympathy towards Mme. Binh not only as a woman but as a member of the Viet Cong as well. It must be noted, somewhat contradictorily, that Mme. Binh was a fierce communist and politician in her own right. Her use of femininity and gender may very well have been a part of her own strategy to win over the international populace. Her choices do not diminish the fact that the northern government used her presence to their advantage. Personal agency and exploitation are not mutually exclusive.

Vietnamese Women’s Motivations And Agency

We cannot view Vietnamese women through the lens of Western feminist expectations. Vietnamese culture is different from the U.S. and other Western countries. Therefore, Vietnamese women’s desires and motivations are unique and should not be distorted by a Western perspective. For example, motherhood in Vietnamese culture is considered part of a woman’s identity and is something most women yearn for. It is also something for which the government praised women, even before their military service.[64] We cannot judge them for perpetuating traditional gender norms and female inferiority that their culture deems a necessary aspect of women’s lives. Similarly, in regard to women’s motivations for joining the war effort, one cannot say with reasonable certainty that the majorityof women were fighting for freedom and equality rather than other motivations. Feminism and liberation were certainly a motivating factor for some, but not all. American and Western women would assume that Vietnamese women fought for the freedom promised them by the northern government since American women at that time were fighting a similar social and political battle at home. However, equality was only one of many motivations that Vietnamese women claimed for participating in the war. Some may argue that citing motherhood and the desire to be a wife as a major motivating factor denies women’s agency and ability to make decisions for themselves. This is simply not true since wife and mother are genuine roles that Vietnamese women craved and were willing to fight for. It could be argued that due to gender norms and societal pressure, women have been conditioned to desire those roles. However, that suggestion implies that Vietnamese women weren’t able to think for themselves. The complexity of women allows them to have multiple and contradicting motivations, all of which are valid.

A major piece of rhetoric that the North Vietnamese government used to encourage women to fight was the notion of “national salvation,” or the liberation of Vietnam from French and American occupation. Beginning during the French War, Ho Chi Minh openly supported women’s equality and linked women’s freedom to national freedom, and women’s exploitation to colonial rule. His claims suggested that one freedom could not be had without the other, and that women’s liberation could only be achieved through “national salvation.”[65] In July 1966, Ho Chi Minh called the entire population to arms and encouraged men and women to support the armies.[66] It should be noted that while women were encouraged to join the war, they were still expected to preserve their feminine behavior and characteristics.[67] By promoting patriotism and connecting the oppression of women with national oppression, Ho Chi Minh was able to unify women seeking equality to fight the American enemy.[68] Women living in rural and urban communities experienced different expectations from which some sought to free themselves. For example, although rural communities did have stricter moral codes, rural women were able to work out in the field with the men while urban women were often confined to their homes.[69] Ho Chi Minh’s promise of freedom gave some women the hope that their positions within society could change only after they defeated their county’s enemies. As the most vulnerable group, women were likely to stand behind a cause if promised future equality. By linking women’s issues with the nation’s issues, the North Vietnamese government gained an incredibly determined force willing to fight for Vietnam’s freedom. By promising equality, women would feel indebted and loyal to the government. They would use the war as a way to prove their skills and capabilities to men. Equality is noted in the official Viet Cong regulations. However, it insincerely claims that the Viet Cong fight for equality, yet later states that “freedom and rights will be discussed further.” This suggests that there were no current plans for women’s equality or their status in politics and culture.[70] It is clear that women’s equality wasn’t truly a priority for the North Vietnam government but women were an asset that they were more than willing to utilize during the war.

In addition to patriotism and “national salvation,” family and tradition also played a role in women’s motivations for joining the war. Women desired not only to live up to their warrior women ancestors, but also to their fathers, mothers, and other family members who fought against the French.[71] Pressure from the government and family members motivated some women to join the cause out of a sense of duty, while others were terrorized by their local Viet Cong unit, forcing them to support the North by spying on the enemy and stealing supplies.[72] In some cases, women’s motivation wasn’t anything grand or overly complex. Sometimes it was just born out of necessity. When one is completely immersed in a conflict, one is forced to choose a side. With their families and homes under fire, some women simply stepped up to protect their way of life. If their homes and livelihoods were destroyed, then they had no future. There would be no place for them to raise their families.[73] These women fought a war for future peace.

One aspect of the future that women sought to protect was the ability to become a wife and mother. Times of war are hardly conducive to raising a family, so many women joined the war in order to save their future and to one day have the peace needed to make their own families. Becoming a mother (and birthing a son) was considered the ultimate achievement for women.[74] In order to one day achieve that goal women were willing to risk their lives and do whatever was asked of them. Because motherhood was considered a sacred right, women fought, not only for the possibility of having a husband and children in the future, but also for the expectation that those achievements would be granted to them after the war. As mentioned previously, female veterans found numerous ways to manipulate gender norms in order to have the children for which they fought so hard.

Through interviews and memoirs, it is clear that women had multiple motivations in joining the war. There is no reason to assign only one motivation to these women since they are complex beings capable of taking action for a number of different reasons. Could a woman not have combined her love and commitment to her country with the need to avenge the deaths of her loved ones? Could a woman have fought for equality while also fighting for her future role as a mother and wife? Vietnamese women fought for duty, family, nation, and themselves at the same time, and did so with great determination.

Postwar Circumstances

Author William Turley, suggests that wars force nations to “reduce their inequalities” and create a more equal atmosphere.[75] However, in the case of Vietnam, after the war inequalities grew or reverted to past inequalities as the nation fell back into traditional gender norms and a Confucian culture. Put somewhat differently, during the war women were judged to an extent by their ability to perform traditionally male tasks, but their “postwar positions within their communities hinged on how well they could preserve their womanly qualities.”[76] During the war, instead of gaining respect for their roles and contributions, women were most often praised for retaining their femininity. After the war, rather than push for changes in gender culture, the Vietnamese government encouraged women to return to their roles as mother, wife, and other domestic roles. In its drive to emphasize family and national unity, the government downplayed gender equality and reinforced patriarchal structures.[77] Despite having some identical roles as men during the war, women were not considered completely equal as they faced the feminine expectations of their male comrades.

The fact that Vietnamese women had better opportunities to obtain education and better paying jobs might tempt one to argue that they achieved greater equality. But in reality, culture and gender norms formed over centuries proved difficult to change despite adjustments to the law. Strong education and professional advancements were promoted for women, yet societal pressure, contingent on government propaganda and encouragement, demanded that women take up traditional roles previously determined by Confucian standards. Women’s more “appropriate” jobs in education and healthcare reflect this traditional thinking. They are extensions of domestic household and family roles that women were expected to uphold, which included educating their children and aiding the sick. Women had the ability to join the workforce or gain an education. Although some female veterans were given more respect, there were many who were often met with prejudice and inequality.[78] They were still expected to balance a traditional home life that included a husband and children to care for. In addition, the purpose of women’s education was to teach them how to best provide for their family through the correct manner of dress, actions, and care. When positive propaganda failed, the government turned to critique and judgement in order to keep women in line with party ideas.[79] During the war, a complexity of contradictions arose in which women were treated both equally and unequally by men in the field and those in leadership positions. It is short-sighted and a generalization of women’s treatment to consider them as completely equal to men during wartime. Women’s inequality was a deliberate choice, as can be seen in the laws and cultural practices at the time. The nation worked to exploit women both militarily and productively. Turley also suggests that war was used as an opportunity to change women’s status for the better, citing that social change leads to changes in women’s roles.[80] However, rather than the war being an opportunity to improve the status of women, the assurance of equality promised by the North Vietnamese government presented the opportunity to further the war’s needs and utilize women. Using war to improve women’s cultural positions meant that the government took an active role in prioritizing women’s needs. But this isn’t true since there was no significant change in the culture. Instead, women were pushed back into traditional norms. The government saw an opportunity to gain from women and took steps to ensure women’s support and exploit their temporary roles.

The Women’s Association took an active role in propagating and perpetuating the government’s push for increased femininity and the importance of family life. Population growth was seen as a concern to the nation’s economic development by leaders. This can be seen through the government’s preservation of the two children limit in order to control overpopulation. Yet cultural norms continued to emphasize women’s fertility and the bearing of sons. Neither the Women’s Association nor the Vietnamese government addressed this contradiction.[81] This discrepancy stands as an example of the way in which a peoples’ culture often supersedes the law and has a greater influence over individual’s actions and decisions. While the Women’s Association provided vocational training to women and launched domestic violence campaigns, their focus remained on femininity, domesticity, and the family unit rather than the individual. All of these concepts were promoted by the government. The government supported women in the workforce as long as they properly raised a family and committed to the nation’s productivity. It wasn’t the individual woman that mattered. Rather, it was the usefulness she had in supporting the nation and perpetuating the government’s preservation of traditional gender norms.

Vietnam’s step back into traditional gender norms also resulted in women being written out of the narrative. Their combat and support roles were twisted into stories of nurturers and lovers. This can be seen via a statue at the cemetery at Dien Bien Phu that features two women shielding a young soldier.

While this memorial recognizes women’s commitment and contribution to the war, the women aren’t shielding the boy with weapons or a literal shield. Instead, they hold up a large strip of fabric over the boy’s head. This statue emphasizes nurturing, domesticity, and “feminine” protection. Thus, even monuments commemorating women only emphasized their feminine qualities and roles during the war. Women’s postwar circumstances provide insight into the North Vietnamese government’s motives and their exploitation of women. It is clear that the government never made women a priority, despite assurances to the contrary, and neglected to care for them in the aftermath.[83] Government leaders were too desperate during the war to care about the former, and too indifferent to care about the latter after the war ended.

Conclusion

Vietnamese women performed a variety of roles during the French and American wars. Their roles both challenged gender norms and also supported and played into them. Women maintained certain traditional gender concepts, such as femininity and motherhood, while simultaneously acting in roles that directly contradicted perceived gender norms. Communist leaders in North Vietnam intentionally manipulated Vietnamese women into contributing to the war effort by playing on their hopes of greater equality at war’s end. Women’s participation in the war similarly allowed the North Vietnamese government to manipulate Vietnamese men since Vietnamese gender expectations placed increased pressure on men to retain their dominant positions over women. Also, due to the Cold War gender culture in America, American military leaders and G.I.’s viewed Vietnamese women as submissive and weak. This, in turn, made Americans vulnerable to the use of Vietnamese women as spies and combatants. It is clear that Vietnamese women were not just defined by their domestic and feminine traits as the familiar narrative would have you believe. Rather, Vietnamese women participated in war by organizing missions, engaging in espionage, and assuming roles such as guerrilla fighters, guides, and gunners. They simultaneously conformed to and contradicted gender norms through their diverse combat and support roles.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

1966 President Ho Speech to Women’s Federation Reprinted. 2360610012 October 1966 Box 06, Folder 10. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 08 – Biography. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/291296.

Article – The Vietnamese Women’s Tradition of Labour and Struggle. 2322025007 1974 Box 20, Folder 25. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 06 Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2digital_objects/173392.

Bernier, Donald W., Frederica M. Bunge, Frances C. Rintz, Rinn-Sup Shinn, Harvey H. Smith, and Suzanne Teleki. DA Pam No. 550-55: Area Handbook for South Vietnam. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967. Accessed February 3, 2019. http://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p4013coll9/id/934.

Captured Documents (CDEC): Report of Vietcong Espionage Activities. F034600771351 20 April 1967 Box 0077, Folder 1351. Vietnam Archive Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed March 7, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/414661.

Captured Documents (CDEC): Unknown Interrogation Source, Log Number 08-1796-06. 1967/08/11 Reel 0153 Vietnam Archive Collection, The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed March 7, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/cdecs/48207.

Captured Documents (CDEC): Vietcong Military Proselyting Teams, Dien Ban District. F034601442135 08 December 1966 Box 0144, Folder 2135. Vietnam Archive Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed March 7, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2digital_objects/491934.

Clipping: South Vietnam Women Guerrilla’s Role Described by Granma, Havana. 2131307005, 10 March 1969 Box 13, Folder 07. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 02 – Military Operations. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2digital_objects/218035.

Girls Encouraged To Display Vietnamese Qualities. 2320413002, 16 May 1970 Box 04, Folder 13. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 06 – Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/116645.

Hanoi Cloaks a decade of Vietcong Terror. 2311311001 May 1967 Box 13, Folder 11. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed March 7, 2019. https:/vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/143264.

Leaflet, 4th PSYOP GP – The Present Role of Vietnamese Women. 20580501011 November 1968 Box 05, Folder 01. Fred Walker Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https:/vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/621092.

Madame Negotiator. 2361001034 07 April 1968 Box 10, Folder 01. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 08 – Biography. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed March 7, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2digital_objects/320067.

Mme Dinh Reviews NLF Women’s Participation in Armed Struggle. 2311104038 08 March 1971 Box 11, Folder 04. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/133250.

Nguyen, Dinh Thi. No Other Road to Take: Memoir of Mrs. Nguyen Thi Dinh. Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program Publications, 1976.

NLF Liberated Area Regulations: 1966. 2311512017 1966 Box 15, Folder 12. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed March 12, 2019. https:/vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/151661.

Pocket Guide, U.S. Department of Defense, DoD PG-21A—A Pocket Guide to Vietnam. 0260102007 05 April 1966 Box 01, Folder 02. Jackson Bosley Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed January 29, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/35893.

Publication of the Department of the Navy, U.S. Marine Corps – NAVMC 2616 Unit Leaders Personal Response Handbook. 1370321001 12 October 1967 Box 03, Folder 21. United States Armed Forces Manuals Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/62385.

Responding to the Party, Government Appeal – In Praise of Women’s Role in War Effort. 2320903025 17 December 1970 Box 09, Folder 03. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 06 – Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/129931.

Review of Liberation Women’s Achievements. 2311101007 03 March 1970 Box 11, Folder 01. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/132445.

South Viet Nam Women on the Front of the Anti-US Struggle. 2311013034 March 1970 Box 10, Folder 13. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/132360.

South Vietnamese Women Valiant on the Frontline Dedicated in the Rear. 2311008017 April 1967 Box 10, Folder 08. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/130822.

Study, Research and Analysis Studies – Liberation Women’s Association – Record of MACV Part 2. F015900230526 12 February 1967 Box 0023, Folder 0526. Vietnam Archive Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/567658.

U.S. Navy Personal Response, Series A-25 – Vietnamese Women – re: sketch of elderly woman and description of the traditional role of women in Vietnamese village society and why she’s relevant to the American mission. 1070301006 No Date Box 03, Folder 01. Glenn Helm Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2digital_objects/71184.

United Nations. No. 13295-(a) United States of America, Democratic Republic of Viet-nam, Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Viet-nam and Republic of Viet-nam: Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Viet-Nam, Signed at Paris on January 27, 1973. United Nations Treaty Collection. Accessed March 27, 2019. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20935/volume-935-I-13295English.pdf.

VC Women Guerrillas Lead Normal Lives Before U.S. Troops. 2311709043 22 October 1969 Box 17, Folder 09. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 05 – National Liberation Front. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/164103.

Women in the Winter-Spring Campaign – Vietnam Documents and Research Notes. 3671424001 01 April 1968 Box 14, Folder 24. George J. Veith Collection. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2/digital_objects/234265.

Women Still Seen In Secondary Role in Family Life Despite Equal Rights. 2320413026 27 February 1971 Box 04, Folder 13. Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 06 – Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://vva.vietnam.ttu.edu/repositories/2digital_objects/116800.

Secondary Sources

Borton, Lady. After Sorrow: An American among the Vietnamese. New York: Kodansha International, 1996.

Borton, Lady. “Behind the Scenes, in the Forefront: Vietnamese Women in War and Peace.”

ASIANetwork Exchange: A Journal for Asian Studies in the Liberal Arts 25, no. 1 (2018): 7-59. Accessed October 3, 2018. https://www.asianetworkexchange.org/articles/10.16995/ane.276.

Gulzow, Monte, and Carol Mitchell. “Vagina Dentata’ and ‘Incurable Venereal Disease’

Legends from the Viet Nam War.” Western Folklore 39, no. 4 (1980): 306-16. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://www-jstor-org /stable/1499999.

Hayslip, Le Ly., and Jay Wurts. When Heaven and Earth Changed Places: A Vietnamese Woman’s Journey from War to Peace. New York: Doubleday, 1989.

Jeffords, Susan. The Remasculinization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Lawson, Jacqueline E. “She’s a Pretty Woman … for a Gook’: The Misogyny of the Vietnam War.” In Fourteen Landing Zones: Approaches to Vietnam War Literature, 15-37. Edited by Philip K. Jason. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991. Accessed October 3, 2018. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.ycp.edu:8000/stable/j.ctt20h6snf.6.

Nguyen, Van Ky. “Rethinking the Status of Vietnamese Women in Folklore and Oral History.” In Viet Nam Expose: French Scholarship on Twentieth-Century Vietnamese Society, 87-107. Edited by Gisele Bousquet and Pierre Brocheux. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Pettus, Ashley. “Between Sacrifice and Desire: National Identity and the Governing of Femininity in Vietnam”. The Journal of Asian Studies 64, no. 1 (Feb., 2005): 256-257. Accessed March 22, 2019. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ycp/detail.actiondocID=182822#.

Stur, Heather Marie. Beyond Combat: Women and Gender in the Vietnam War Era. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Sutton, Caroline. “Baby in One Hand, Sword in the Other.” The North American Review 294, no. 1 (2009): 3-6. Accessed October 03, 2018. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.ycp.edu:8000/stable/20697702.

Taylor, Sandra C. Vietnamese Women at War: Fighting for Ho Chi Minh and the Revolution. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1999.

Turley, William S. “Women in the Communist Revolution in Vietnam”. Asian Survey 12, no. 9 (1972): 793-805. Accessed March 21, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2642829.

Turner, Karen Gottschang, and Phan Thanh Hao. Even the Women Must Fight: Memories of War from North Vietnam. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

Vietnamese Women’s Museum. Accessed February 26, 2019. http://www.baotangphunu.org.vn.

Waibel, Gabi and Sarah Gluck. “More Than 13 Million: Mass Mobilization and Gender Politics in the Vietnam Women’s Union.” Gender and Development 21, no. 2 (2013): 343-361. Accessed March 22, 2019, https://doi:10.1080/13552074.2013.802148.