By: Victoria Good

Introduction

Today, field hockey is a widely popular sport for women in the United States. There are thousands of private clubs nationwide, and many public middle and high schools have women’s field hockey teams. There is a U.S. national team who competes against other countries’ teams regularly and participates in the Olympic games. Over a million American girls play field hockey each year. However, this was not the case before 1901, when an extraordinary woman named Constance Applebee arrived in Philadelphia.

Field hockey is a highly technical sport played with a wooden or fiberglass stick and a hard plastic ball. The stick is curved at the end, and the ball can be hit, dribbled, lifted, and pushed. The ball cannot touch the player’s body at any point. Field hockey can be played outside on grass or turf, with eleven players on each side. It can also be played indoors on a hard-court surface, with six players per side. Strength, speed, stick-handling skills, and hitting power are all critical for field hockey athletes.

In 1901, the athletic and energetic Englishwoman Constance Applebee arrived in the United States to expand her career in physical education and introduce field hockey into the country. Field hockey had been popular in Great Britain for both men and women for years, and Applebee believed it could be successfully established in American society, too. However, she faced significant obstacles. In a speech she gave 50 years after she first began promoting hockey in the U.S., Applebee acknowledged these difficulties: “At that time, there were two schools of thought regarding games for women. One that women should do no active sports, and the other, that women could do anything a man could. Even tennis was frowned upon by many prominent doctors as being too boisterous and fatiguing for the female sex.”[1] Obtaining public acceptance for a competitive and somewhat aggressive women’s sport was a daunting task in 1901; however, Applebee was hugely successful, using aspects of the American culture around her to achieve her goals.

Though Applebee was recognized for her hard work and her influence on field hockey during her life, historians have not given her the same appreciation. Much of the historiography on American women’s sports ignores Applebee completely and instead centers itself on later milestones like Title IX or well-known names like Billie Jean King. Title IX and King’s famed tennis match were the sole focus of scholar Susan Ware’s book, Game, Set, Match, in which she argued that these events in the 1970s marked the “revolution” in women’s athletics in America.[2] As Applebee’s story demonstrates, however, the revolution in female athletics began almost a century earlier. In the textbook Women and Sport: Continuing a Journey of Liberation and Celebration, editor Ellen Staurowsky includes only a short introductory chapter on the history of women’s athletics before Title IX and does not mention Constance Applebee.[3] The following fourteen chapters focus on female sports in America after the landmark Title IX. In the 2021 children’s book, We Got Game!: 35 Female Athletes Who Changed the World, names like Nancy

Lopez, Serena Williams, and Billie Jean King are given celebratory biographies.[4] Constance Applebee is left out, despite the fact that her life’s work paved the way for other American women to participate in competitive sports. Applebee is also neglected by virtually every historical work on the women’s rights movement, even though she was undeniably an influential figure in the fight for gender equality in the United States. Applebee deserves far wider recognition by the American public than she has been given thus far.

The story of Constance Applebee’s establishment of field hockey in the U.S. is important not only because it has impacted young women for decades, but also because it demonstrates the significance of four themes in nineteenth and twentieth century American history: first, the creation of female-only environments by women; second, the utilization of traditionally feminine values to gain public acceptance; third, the beginning of physical education in the country; and fourth, the cooperative yet competitive relationship between British culture and American culture.

Targeting Elite Female-Only Environments

When Constance Applebee arrived in the United States to establish field hockey in 1901, she focused her efforts on female-only colleges, like Bryn Mawr College, Vassar College, Smith College, Mt. Holyoke College, Radcliffe College, and Wellesley College. The students attending these colleges were middle- to upper-class, young women. Field hockey was not a women’s-only sport in England: the first professional hockey club, Blackheath HC, was founded in London in 1849 for men only.[5] Applebee was not bound by any tradition to introduce field hockey to exclusively women, and her choice to target colleges specifically, rather than attempt to start youth programs, was likely strategic.

According to scholars, it was not uncommon in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for American women to form networks of meaningful connections with other women. Historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg famously revealed this phenomenon in her 1975 research based on diaries and correspondence written by women in the 1800s.[6] Smith-Rosenberg found that a “female world” existed beyond the scope of men’s involvement, largely due to the societal separation of men and women. Women formed strong emotional bonds with each other because they shared similar life experiences that were wholly opposite to the experiences of men.[7] Shortly after, in 1981, prominent sociologist Jessie Bernard concurred with Smith-Rosenberg in her book Female World. Bernard wrote, “All these distinct and compulsory occupations are so many natural barriers, which, by keeping the two sexes asunder, render the solicitations of the one less frequent and less ardent and the resistance of the other more easy.”[8] Since men and women were often separated by society, each group found it far easier to form connections with others within their same-sex group than with their opposite-sex group.

Other scholars have also written about the distinct female “world” that existed in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Historian Marilyn Ferris Motz wrote of the strong connections between female family members and how these relationships impacted marriages, property rights conflicts, and legal processes. She gave an example of a family of sisters who “aligned themselves against a brother-in-law, advising their sister to divorce him and offering her financial assistance.”[9] Strong networks of female relationships helped women in the late 1800s thrive in business, too, according to historian Lucy Eldersveld Murphy. In her research on businesswomen in the American Midwest from 1850-1880, Murphy found that the support and service of other women were vital to those running businesses. She wrote, “Milliners, dressmakers, seamstresses, and fancy good merchants—roughly three quarters of the total group-catered almost exclusively to a female clientele. That exclusiveness can be understood more clearly in the context of the nineteenth-century female subculture based on women’s friendships and kinship ties.”[10]Clearly, the “world” of female connection was a powerful social phenomenon that had the potential to benefit the women inside of it. Constance Applebee, upon arriving in America in 1901, chose to access this “world” through aligning herself with female-only colleges.

Applebee’s motivation for targeting women’s colleges was probably not driven entirely by an attempt to cultivate a female-only environment around field hockey. The students who were attending these institutions were also defined by their class. Most of the women were white, although a small number of black students were also admitted throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s.[11] However, each of the colleges where Applebee introduced field hockey were considered to be prestigious and elite.[12] The women who attended Smith, Wellesley, Vassar, Mt. Holyoke, Radcliffe, and Bryn Mawr likely had some degree of influence, independence, free time, and wealth. Therefore, they would be prime candidates for the introduction of a new sport. Nonetheless, the importance of utilizing female connections in the women-only atmospheres of the colleges is evident throughout Applebee’s career.

Among the correspondence Applebee saved in her personal files were many letters from administrators and faculty from the schools she visited to demonstrate field hockey. Several, which were overwhelmingly positive, were written by female educators and administrators. Applebee also kept one negative letter written by the male General Committee at Syracuse University, even though it wasn’t addressed directly to her. The letter was written in 1924 to a “Miss Wesson” and chided her for hiring a new member to the school’s field hockey coaching staff, of whom they did not approve. The General Committee disapproved of Miss Wesson’s appointment because she did not “seem interested in [the] American ideals of athletics for women.”[13]A better candidate, the letter stated, would be one the Committee could “count on for cooperation in the constructive rationalization we are trying to bring about in athletics for women.”[14] It is up to a reader’s interpretation as to the meaning of the principle ‘constructive rationalization’ in women’s sports. Perhaps the new appointee was too outwardly emotional, high-spirited, or too progressive in her promotion of female athletics and therefore unacceptable at Syracuse. Though it is unknown why Applebee kept the letter or what specific issues the Syracuse General Committee had with Miss Wesson’s new appointee, this correspondence contrasts sharply with letters Applebee received from various female administrators. For example, Pattrice Ruth O’Keefe, the Assistant Director of Health and Physical Education from a school in Kansas City, wrote glowingly of a short visit to her school by Applebee. She described Applebee’s demonstration of field hockey as educational and “inspirational” and wrote that Applebee had succeeded in convincing herself and the other administrators of the “need for…an adequate playing space for girls.”[15] The difference between the discouraging correspondence from male administrators and the affirming correspondence from female administrators suggests it was far easier for Applebee to convince other women of the importance of field hockey (and the need for women’s sports more broadly) than for her to convince men. Thus, the introduction of field hockey into female-only environments seems a logical choice for Applebee to have made.

Applebee also cultivated the women-only world of field hockey in ways other than targeting women’s colleges. She founded and edited America’s first girls’ sports magazine, The Sportswoman. This magazine, circulated for women interested in athletics, only published articles written by other women. Issues of The Sportswoman covered a wide range of topics, included tips on choosing the right field hockey stick, printed pictures of teams of girls from England and the U.S., and even touched on subjects within the debate over women’s participation in sports, such as appropriate uniform length and safety.[16] The female-only nature of The Sportswoman again shows how Applebee chose to utilize the exclusive women’s “world” that existed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A 1963 newspaper article, reflecting on Applebee and field hockey’s growing popularity, addressed the female nature of the sport: “Who wins is less important than the principle that women, in a world dominated by men, get a chance to know each other, and to run their own sports…It clings to the theory that women can jolly well take care of themselves. Field hockey and women’s lacrosse are the only sports completely controlled by women.”[17]Field hockey is still played by an overwhelming majority of women in America, even though men dominate the sport around the rest of the world. While opportunities for women are widely available in every state, only three annual tournaments in the U.S. offer boy’s divisions, according to the United States Field Hockey Association (USFHA).[1] [18]

Applebee’s cultivation of an exclusively female atmosphere around field hockey not only proved to be successful in her institutionalization of the sport in the early 1900s, but also had a heavy influence on American hockey for decades to come.

Use of Traditional Feminine Values

The fight for female equality in the United States has a long and complex history. Though many women’s rights movements in the U.S. were radical and revolutionary, there have also been social shifts that depended upon more traditional views of women. In 1978, women’s historian Ruth Bloch published her article, “American Feminine Ideals in Transition: The Rise of the Moral Mother, 1785-1815,” in which she argued that the American popular literature from the seventeenth century through the early nineteenth century clearly demonstrated the traditional cultural values associated with women and mothers.[19] Bloch writes that women were considered to be “…virtuous, pious, tender, and understanding.”[20] These values have been associated with femininity since America’s founding. Bloch’s findings corroborate with historian Barbara Welter’s earlier article, published in 1966, in which Welter discussed “true womanhood”. Welter wrote that in nineteenth century America, a ‘true woman’ possessed the attributes of “piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity.”[21] Counterintuitive though it may seem, many women’s rights movements have utilized these social values to further their cause, and Constance Applebee’s introduction of field hockey into the United States is no exception.

When America won its independence from Great Britain in the late eighteenth century, the new nation was faced with the daunting task of establishing its own political and social structure. This included defining societal roles for all Americans. Widespread concern for the future of the republic led to an increased emphasis placed on the need for ‘virtuous’ citizens, as it was believed that the new democracy could only last as long as the population supported it. Women, who were traditionally believed to be inherently virtuous, were assigned a political role that included raising their children to be good citizens. This ideology came to be known as “republican motherhood,” a phrase coined by historian Linda Kerber. In 1976, in the wake of the 1960s feminist movement in America and the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Kerber wrote her landmark article “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment-An American Perspective,” which described women’s social and political roles in the early years of the American republic. Kerber argues that the political role early Americans developed for women was based on both Enlightenment ideals of republicanism and the belief that women belonged exclusively in the domestic sphere.[22] She also argues that American women’s educational opportunities were significantly expanded due to republican motherhood ideas. If the virtuous women of the United States were to raise their children successfully, they had to be adequately educated.[23] Thus, American women’s opportunities were broadened in the wake of the Revolutionary War because women were given a defined political role and experienced greater access to education. This happened largely through the utilization of traditional feminine values such as motherhood and virtue.

Post-revolutionary era American women were not the last to experience a shift in social opportunity related to traditional feminine values. As the country moved towards the Civil War in the mid-1800s, many American women were becoming missionaries, according to historian Amanda Porterfield. In her book Mary Lyon and the Mount Holyoke Missionaries, Porterfield argues that female American missionaries had a significant role in foreign missionary work and the expansion of women’s rights in the early nineteenth century. The traditional feminine values of piety and meekness allowed women to step into these missionary roles. Porterfield writes, “Missionary work celebrated these traditional Puritan values, offering women new opportunities for passionate self-expression and social activism… and enabling them to become virtuosos of Christian devotion with degrees of influence and public recognition they could not have otherwise pretended.”[24] Porterfield’s research demonstrates that feminine values continued to be a factor in the expansion of women’s opportunities throughout American history.

Constance Applebee’s successful introduction of field hockey into American culture in the early twentieth century depended largely upon an adherence to traditional feminine values, too. Although evidence suggests that Applebee had a fiery personality and liked the intensity of field hockey, her public portrayal of the sport was often carefully attached to principles such as gentility, gracefulness, and tenderness. Constance Applebee and her advocacy for American girls to play sports is part of a broader historical theme of women’s rights movements utilizing the cultural values traditionally associated with femininity.

Virtually every newspaper article published in the early 1900s describing Applebee and her introduction of field hockey characterizes the sport as physically graceful and gentle, and able to help girls develop into disciplined, ladylike young women. In fact, Applebee herself directly refuted any claims to the contrary in the Boston Sunday Journal: “There is no danger in the game, nor is it in the least degree rough or un-womanly.”[25] The conscious effort by Applebee and her supporters to portray field hockey as “ladylike” or “gentle” was largely successful. A 1902 newspaper article reporting upon Applebee’s introduction of hockey to the Emma Willard School in New York was quick to assure its readers that field hockey “…affords vigorous exercise without any features of boisterousness. When properly played, it is not as rough as basketball.”[26] Another newspaper article from Poughkeepsie, N.Y., described the sport of field hockey for its readers after Applebee had visited and assisted in forming the Poughkeepsie Hockey Club. When reporting on the types of girls who made good field hockey players, the article defined them as “self-contained” and “girls of steady nerves.”[27]The early portrayal of field hockey to the American public is directed by a narrative that describes the sport as “gentle” and suitable for girls with calm dispositions. The success of this narrative is demonstrated by its longevity: a 1963 headline for an article in The National Observer, which referred to Applebee as the “grand duchess” of field hockey, read, “Field Hockey: It’s a Lively but Ladylike Sport.”[28]

The contrast between the delicate nature is clearly demonstrated by (albeit affectionate) reports of her coaching style from her former players. An article from an unidentified publication, which Applebee had cut out and kept in her collection of papers, illustrated her commanding and assertive nature. “Apple-isms,” written by former player Laura Ham, recorded some of the types of insults Applebee hurled at her athletes during competition. “No wonder you can’t get around to make a goal, look at those fat legs, they’re like the pillars of a church,” Applebee yelled at one girl.[29] “That’s alright, she plays better than you old hens,” she informed another athlete, who had just expressed concern about a beginner being put in the game.[30] A letter written in 1946 by Bryn Mawr graduate Jessie Thomas Bennett reveals her own experiences with Applebee’s ferocity, as well as with field hockey’s occasionally brutal nature. She wrote, “Hockey is my pleasantest memory of college. Crisp sunny autumn days and Miss Applebee shouting ‘don’t stand there Thomas admiring your shot, make another one.’ I still have scars on my shin bone from Adeline Havemeyer’s hockey stick.”[31] Bennett’s memories indicate that the representation of field hockey as gentle did not reflect reality.

Applebee’s powerful personality was not exhibited only on the hockey field: a 1950s article from the Bryn Mawr College newspaper College News, reflecting upon its founding, credited Applebee for her determination and vigor. “The idea of a paper met a great deal of opposition at first,” recalled one alumna, “[and] we would have given up if it had not been for Miss Applebee. Miss Thomas said the college was too small to need a newspaper or to pay for one – but she gave in to Miss Applebee, who she said would go ahead anyway.”[32] Applebee’s assertive personality was well-known to those around her and was diametrically opposed to the demure personality that field hockey was supposed to encourage in young women, according to popular media representations.

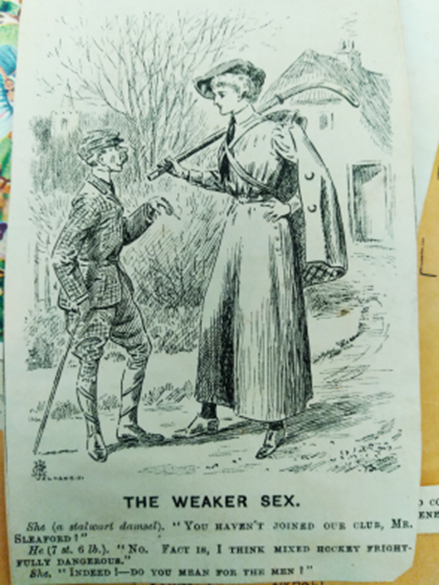

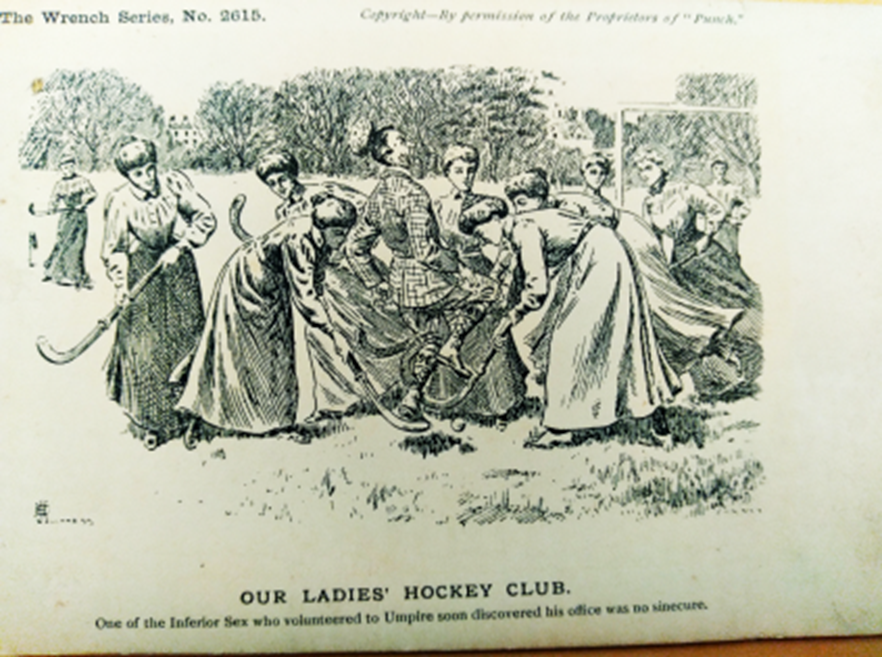

Applebee also probably did not believe that field hockey wasn’t “rough” or “unwomanly.” Though she released statements in the press describing the sport as gentle, two humorous cartoons she kept in her personal notebooks suggest she may have privately thought otherwise. While perhaps only for entertainment, the cartoons imply that field hockey is a rowdy and high-spirited game, which might convey Applebee’s views more accurately than her newspaper interviews do. Both cartoons also poke fun at the idea of men attempting to involve themselves in field hockey, further evidence that Applebee believed in cultivating a female-only atmosphere around the sport.

Connection to Physical Education

Prior to the late nineteenth century, physical education was not formally included in American public or private schooling. During the late 1800s, physical education programs were institutionalized for the first time, corresponding with a widespread recognition of the benefits of physical exercise. In his book on the history of physical education, Emmett Rice described the period between 1850 and 1860 as a time of significant expansion in the acceptance and establishment of physical education programs.[33]Rice writes, “There was an increase in the amount of literature on the subject…Dr. Windship, the apostle of great strength, demonstrated and lectured to thousands…Harvard built her first gymnasium.”[34] Physical education was burgeoning in the mid-to-late 1800s. According to historian Martha Verbrugge, this was due largely to the work of the first physical educators themselves, who advocated for the training of PE teachers and the formation of programs in schools.[35] Other social forces impacted the growth of physical education, too, as historian Patricia Vertinsky argued in her book The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors, and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century. According to Vertinsky, many doctors in the nineteenth century believed that physical exercise was necessary for women to successfully give birth and become healthy mothers, and thus became proponents of female physical education.[36] Whether due to social factors, increased awareness of the benefits of physical fitness, or the advocacy of physical educators, late nineteenth-century America experienced an expansion of physical education programs in schools. Constance Applebee, who arrived in the U.S. in 1901, attached herself and her work to the recent physical education movement.

Another significant way Applebee linked field hockey to physical education was by using the college programs and their faculty to reach students. Applebee, who became Bryn Mawr College’s physical education director, often contacted other physical educators to arrange demonstrations of field hockey. A paper on the subject of Applebee’s life and accomplishments, probably written by one of her former students, described her relationship with the physical education teacher at Vassar: “This incident of close cooperation between Miss Applebee and Miss Ballentine illustrates the relationship the young English teacher held with the physical training director at Vassar College.”[37]Applebee herself said in a 1951 speech that Miss Ballentine helped by “[writing] to the other Eastern colleges suggesting that they should try the game too, and that fall I spent a week at Smith, Wellesley, Mt. Holyoke, Radcliff and Bryn Mawr.”[38]This demonstrates not only Applebee’s use of physical educators to help her spread field hockey, but also the importance of her connections with other women.

However, physical health concerns were still a significant roadblock to the institutionalization of female sports. The transcript of a 1922 Amateur Athletics Union meeting, published in the N.Y. Herald, made this clear. One representative at the meeting rose and said, “I am not opposed to athletics for girls, but I must point out the dangers even of intercollegiate competition in these events. Even with medical supervision disasters have occurred.”[39]Another representative merely responded, “The girls have become athletes. We can’t stop them. We must simply standardize their games.”[40]Applebee and those around her sought to appease the public fear of women being injured while participating in athletics by connecting field hockey to good health and physical education. Applebee was often quoted in newspaper articles expressing sentiments such as, “Hockey is well adapted to the needs of girls and is an interesting and healthful game.”[41]An article in The Sportswoman read, “On the purely physical side, the benefits, among others, are stimulated circulation, freedom from impurities and waste, firm muscles, steady nerves, suppleness, true lines and grace of carriage.”[42]“The game of field hockey…has been highly recommended by American authorities on physical education,” explained an early 1900s news article about Applebee. By aligning herself with physical education programs and promoting the health benefits of field hockey, Applebee worked to increase public acceptance of girls playing field hockey. Applebee’s timing was perfect, as Americans had just begun recognizing the importance of physical education a few decades earlier.

The English Influence

The relationship between Great Britain and the United States has historically been both friendly and competitive. The interconnectedness of the two cultures had significant impacts on the institutions in each country, including sport. In a 2017 article, sports historian Steven Pope explored the connection and competition between British and American sports. This rivalry, Pope argued, led to the development of the global sports industry that includes international contests.[43] However, an interesting complexity lies within the relationship between British and American athletics: most American sports were, in the postcolonial days, formed in imitation of English sports. Pope explained how in the two centuries that followed the American Revolution, American culture absorbed British sports, then developed them to a level that could, in turn, compete with England.[44]Pope’s research demonstrates the complicated but significant relationship between American and British sports.

The tangled relationship between Great Britain and the U.S. in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was not limited to athletics. A subtle struggle for dominance characterized the British and American relationship beginning in the mid-1800s, according to scholar Peter Hugill in his article, “The American Challenge to British Hegemony, 1861-1947.” This included competitiveness in technological advances, naval influence, and economic power.[45] In a 1977 article, British historian J.H. Plumb discussed the interrelated cultures of the two countries, which he described as viewing each other with a “mixture of preoccupation and disdain.”[46] Plumb explains the emulating yet rivalrous aspects of this relationship that encompassed theater, literature, education, painting, and even gardening.[47]The English and the American ways of life were connected in many ways throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, yet the two countries still vied for power and influence. This led to a unique cultural link between Great Britain and the United States.

Great Britain’s influence in America and the two countries’ intertwined cultures played a significant role in Applebee’s introduction of field hockey into the U.S., too. News reports about Applebee and the new sport often referred glowingly to her English roots. A newspaper headline, written sometime between 1901 and 1904, read, “English Girl to Teach Wellesley Students Hockey.”[48] The article that followed quoted Applebee as saying, “It is most extraordinary that the game of hockey has not already been introduced to the American schools and colleges. Girton College at Cambridge, and Somerville College at Oxford, have splendidly coached teams.”[49]The American public seemed both enamored with hockey’s British roots and eager to catch up to the successful institution of the sport in England. The 1902 news article about hockey being introduced at the Emma Willard School begins by discussing the sport’s origin in England: “In Great Britain…all the leading schools for girls there have their splendidly-coached first, second and third elevens and hockey matches.”[50]Applebee herself spoke openly of the vogue English society which embraced women’s field hockey and occasionally compared it to the American society, which was, of course, slightly behind. In an interview for an unidentified newspaper article, likely from 1904, she said, “It is not only fashionable in England, but is regarded as well as distinctly educational.”[51] A newspaper article probably written in 1909 and published in The Brooklyn Daily reported that a group of U.S. teachers traveled to Great Britain to “see how things were done in English schools.”[52]Upon their return, one of these teachers relayed that “The splendid health of the English woman is not due to accident… At one school I saw five acres of English girls in one field playing hockey. Their faces were flushed with exercise and their eyes were dancing like sunlight, and the spur of health could be detected in their every movement. Grace of movement was second only to strong arms, good lungs, and the spirit of health.”[53] This report both supports the notion that field hockey develops healthy, ladylike young women and exhibits the interconnected and oft-competing cultures of Great Britain and America in the early twentieth century. Americans cared deeply about what their English counterparts were up to, as demonstrated by the fact that a group of teachers were sent to investigate British schools. And, much to Applebee’s benefit, the English were playing field hockey.

Applebee’s recognition of the importance of her British background in institutionalizing field hockey in the U.S. is demonstrated by her constant infusion of English culture into her efforts. For years, Applebee ran a summer camp in the Poconos in Pennsylvania, where attendees would come for a week to learn how to play, coach, and referee field hockey. According to the 1933 advertisement for the camp, registrations also included demonstrations of “…other English games, cricket, badminton, stool ball and water polo.”[54]Sports were not the sole focus of the camp’s offerings, either; the advertisement boasted, “in the evenings after the lecture, there will be an hour of English Country dancing.”[55]The inclusion of multiple British activities, even ones unrelated to athletics, suggests a tactical strategy by Applebee. If field hockey was considered by Americans to be not only “fashionable” in England, as Applebee had earlier stated in the press, but also a facet of elite English education, women were more likely to attend a hockey camp that incorporated other stylish recreations from Great Britain than one that did not. Applebee was, it seems, well aware of the connection between field hockey being established in the U.S. and the English role in American culture, and she used this to her advantage.

Conclusion

Constance Applebee leaves behind an incredible legacy. Her positive impact on young girls’ lives was recognized and appreciated during her lifetime, as made clear by letters written to her by her former athletes. Frieda Kitak from the Midwest Field Hockey Association wrote to her in 1966, thanking her for her efforts: “In our great country, field hockey and Miss Applebee are synonymous. We are grateful for your guiding hand…Deep from our hearts, Midwest (and we know the feeling is nationwide) thanks you for all that you have done…Miss Applebee, Midwest pays tribute to you.”[56]At a 1973 Bryn Mawr class reunion, a group of Applebee’s former players signed a note reading, “Dear Apple, The class of 1928 is having its 45th reunion. We are all talking about you, remembering the laughs, good times, and hard hockey. With pride and love, Class of 1928.”[57]Another former Bryn Mawr field hockey athlete wrote, “My dear Miss Applebee, It is with a deeply genuine sense of loss that I have to be absent from that delightful dinner of yours on Saturday. You were so much a gay, vivid, and delightful part of our college days that you will never be forgotten by any of us…As we get older these memories seem to grow more vivid and be more precious with each passing year.”[58]

Applebee’s dedication to establishing field hockey in the United States allowed thousands of women to participate in an enjoyable and competitive team sport when they weren’t able to before. Her impact has only grown in the decades after her death: in 2018, there were 1.46 million girls in the U.S. over the age of six participated in field hockey.[59]Her work also demonstrated the importance of many different aspects of American life and culture in the early twentieth century. She exhibited how social trends and values can be manipulated to achieve a broader goal. Applebee’s extraordinary life story is relevant and valuable to athletes, women’s historians, American historians, sports historians, and activists alike.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Applebee, Constance. “Fifty Years a Growing.” Speech, Bryn Mawr College, 1951. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Bennett, Jessie Thomas. Jessie Thomas Bennett to Catherine McBridge, November 1951. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Bradbury, William, and Frederick Evans. “The Wrench Series.” Punch Magazine. Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Bryn Mawr College Class of 1928. Bryn Mawr College Class of 1928 to Constance Applebee. May 19, 1973. Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Calhoun, Lucy. “A.A.U. To Control Girl’s Athletics.” N.Y. Herald, April 9, 1922. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Cary, Mrs. C. Reed. Mrs. C. Reed Cary to Constance Applebee. Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

“Field Hockey: It’s a Lively but Ladylike Sport.” The National Observer, September 16, 1963. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Ham, Laura. “Apple-Isms.” The Sportswoman, Undated. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

“Hockey Association Formed.” Unidentified newspaper clipping, Poughkeepsie, N.Y. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Kitak, Frieda. Frieda Kitak to Constance Applebee. November 26, 1966. Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Murray, Patricia. “Applebee Fights Opposition to News; Sees Need of Newspaper at Bryn Mawr.” Bryn Mawr College News, [1948-1956]. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

O’ Keefe, Pattrice Ruth. Pattrice Ruth O’Keefe to National Field Hockey Association, October 29, 1937. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

“Opinion of Miss Constance Applebee, One of England’s Leading Women Athletes, Who Has Been Studying the American Girl in Her Work and Play.” The Boston Sunday Journal, [1901-1906]. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Paris, Viola. “Exercise and Proper Clothing.” The Sportswoman, undated. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

“September Hockey and Lacrosse Camp.” Advertisement. 1933. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Syracuse General Committee to Miss Wesson, October 24, 1924. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

“The New Feature at the Emma Willard School.” Unknown newspaper, Troy, N.Y., 1902. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

“The Well-Dressed Hockey Player.” The Sportswoman, June 1929. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Unidentified typescript of biography draft, [1929-1940]. Constance Applebee Papers. Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA

Secondary Sources

Bernard, Jessie. Female World. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982.

Bloch, Ruth. “American Feminine Ideals in Transition: The Rise of the Moral Mother, 1785-1815.” Feminist Studies 4, no. 2 (1978): 102.

“Boy’s Development.” USA Field Hockey. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://www.teamusa.org/usa-field-hockey/usmnt/boys-opportunities.

“Field Hockey: Number of Participants U.S.” Statista. Last modified January 29, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/191655/participants-in-field-hockey-in-the-us-since-2006/.

“History of Field Hockey.” Burke Athletic Club. Last modified June 21, 2016. https://www.burkeathleticclub.org/field-hockey/history-of-the-sport.

Hugill, Peter J. “The American Challenge to British Hegemony, 1861-1947.” Geographical Review 99, no. 3 (2009): 403–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40377400.

Kerber, Linda. “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment-An American Perspective.” American Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1976): 188.

Motz, Marilyn Ferris. True Sisterhood: Michigan Women and their Kin, 1820-1920. United States: State University of New York Press, 1983.

Murphy, Lucy Eldersveld. “Her Own Boss: Businesswomen and Separate Spheres in the Midwest, 1850-1880.” Illinois Historical Journal 80, no. 3 (1987): 174. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40192142.

Perkins, Linda M. “The Racial Integration of the Seven Sister Colleges.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 19 (1998): 104. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998936.

Plumb, J. H. “Britain and America. The Cultural Tradition.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 31, no. 2 (1977): 227–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/531828.

Pope, Steven. “American-British Sporting Rivalries and the Making of the Global Sports Industry.” Comparative American Studies: An International Journal 14, no. 4 (2016): 302-319.

Porterfield, Amanda. Mary Lyon and the Mount Holyoke Missionaries. United States: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Rice, Emmett. A Brief History of Physical Education. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1926.

“Seven Sisters.” New World Encyclopedia. Accessed April 12, 2022. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Seven_Sisters_(colleges).

Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Women in Nineteenth-Century America.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1, no. 1 (Fall 1975), 1-29. doi:10.1086/493203.

Staurowsky, Ellen J. Women and Sport: Continuing a Journey of Liberation and Celebration. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2016.

Verbrugge, Martha H. Active Bodies: A History of Women’s Physical Education in Twentieth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Vertinsky, Patricia. The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors, and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990.

Ware, Susan. Game, Set, Match: Billie Jean King and the Revolution in Women’s Sports. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2011.

Welter, Barbara. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1966): 152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2711179.

Weintraub, Aileen. We Got Game!: 35 Female Athletes Who Changed the World. Running Press Kids, 2021.

[1] Constance Applebee, “Fifty Years a Growing” (speech, Bryn Mawr College, 1951), Box 5, Folder 7, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[2] Susan Ware, Game, Set, Match: Billie Jean King and the Revolution in Women’s Sports (Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2011).

[3] Ellen J. Staurowsky, Women and Sport: Continuing a Journey of Liberation and Celebration (Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2016).

[4] Aileen Weintraub, We Got Game!: 35 Female Athletes Who Changed the World (Running Press Kids, 2021).

[5] “History of Field Hockey,” Burke Athletic Club, last modified June 21, 2016, https://www.burkeathleticclub.org/field-hockey/history-of-the-sport.

[6] Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Women in Nineteenth-Century America,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1, no. 1 (Fall 1975): 1-29, doi:10.1086/493203.

[7] Smith-Rosenberg, “The Female World,” 10.

[8] Jessie Bernard, Female World (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982), 92.

[9] Marilyn Ferris Motz, True Sisterhood: Michigan Women and their Kin, 1820-1920 (United States: State University of New York Press, 1983), 28.

[10] Lucy Eldersveld Murphy, “Her Own Boss: Businesswomen and Separate Spheres in the Midwest, 1850-1880,” Illinois Historical Journal 80, no. 3 (1987): 174, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40192142.

[11] Linda M Perkins, “The Racial Integration of the Seven Sister Colleges,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 19 (1998): 104, https://doi.org/10.2307/2998936.

[12] “Seven Sisters,” New World Encyclopedia, accessed April 12, 2022, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Seven_Sisters_(colleges).

[13] Syracuse General Committee to Miss Wesson, October 24, 1924, Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[14] Syracuse General Committee to Miss Wesson.

[15] Pattrice Ruth O’Keefe to National Field Hockey Association, October 29, 1937, Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[16] “The Well-Dressed Hockey Player,” The Sportswoman, June 1929, Box 6, Folder 32, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[17] “Field Hockey: It’s a Lively but Ladylike Sport,” The National Observer, September 16, 1963, Box 5, Folder 8, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[18] “Boy’s Development,” USA Field Hockey, accessed April 12, 2022, https://www.teamusa.org/usa-field-hockey/usmnt/boys-opportunities.

[19] Ruth Bloch, “American Feminine Ideals in Transition: The Rise of the Moral Mother, 1785-1815,” Feminist Studies 4, no. 2 (1978): 102.

[20] Bloch, “American Feminine Ideals,” 100.

[21] Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1966): 152, https://doi.org/10.2307/2711179.

[22] Linda Kerber, “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment-An American Perspective,” American Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1976): 188.

[23] Kerber, “The Republican Mother,” 189.

[24] Amanda Porterfield, Mary Lyon and the Mount Holyoke Missionaries (United States: Oxford University Press, 1997), 6.

[25] “Opinion of Miss Constance Applebee, One of England’s Leading Women Athletes, Who Has Been Studying the American Girl in Her Work and Play,” The Boston Sunday Journal, [1901-1906], Box 5, Folder 6, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[26] “The New Feature at the Emma Willard School,” Unknown newspaper, Troy, N.Y., 1902, Box 5, Folder 7, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[27] “Hockey Association Formed.” Unidentified newspaper clipping, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., Box 5, Folder 8, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[28] “Field Hockey: It’s a Lively But Ladylike Sport,” The National Observer.

[29] Laura Ham, “Apple-Isms,” The Sportswoman, Undated, Box 6, Folder 32, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[30] Laura Ham, “Apple-Isms.”

[31] Jessie Thomas Bennett to Catherine McBridge, November 1951, Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[32] Patricia Murray, “Applebee Fights Opposition to News; Sees Need of Newspaper at Bryn Mawr,” Bryn Mawr College News, [1948-1956], Box 5, Folder 9, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[33] Emmett Rice, A Brief History of Physical Education, (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1926), 161.

[34] Rice, A Brief History, 161.

[35] Martha H. Verbrugge, Active Bodies: A History of Women’s Physical Education in Twentieth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 14.

[36] Patricia Vertinsky, The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors, and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990)

[37] Unidentified typescript of biography draft, [1929-1940], Box 6, Folder 26, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[38] Applebee, “Fifty Years a Growing.”

[39] Lucy Calhoun, “A.A.U. To Control Girl’s Athletics,” N.Y. Herald, April 9, 1922, Box 5, Folder 6, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[40] Lucy Calhoun, “A.A.U. To Control Girl’s Athletics.”

[41] Unidentified typescript of biography draft, [1929-1940].

[42] Viola Paris, “Exercise and Proper Clothing,” The Sportswoman, undated, Box 6, Folder 32, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[43] Steven Pope, “American-British Sporting Rivalries and the Making of the Global Sports Industry,” Comparative American Studies: An International Journal 14, no. 4 (2016): 302-319.

[44] Pope, “American-British Sporting Rivalries,” 307.

[45] Peter J. Hugill, “The American Challenge to British Hegemony, 1861-1947,” Geographical Review 99, no. 3 (2009): 403–25, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40377400.

[46] J. H. Plumb, “Britain and America. The Cultural Tradition,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 31, no. 2 (1977): 227–43, http://www.jstor.org/stable/531828.

[47] Plumb, “Britain and America,” 234.

[48] “English Girl to Teach Wellesley Students Hockey,” Unidentified news clipping, [1901-1904], Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[49] “English Girl to Teach Wellesley Students Hockey,” [1901-1904].

[50] “The New Feature at the Emma Willard School,” Unknown newspaper.

[51] “Hockey for Girls,” Unidentified news clipping, [1904], Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[52] “New Era in School Athletics Inaugurated at Erasmus Hall,” Unidentified news clipping, [1909], Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[53] “New Era in School Athletics Inaugurated at Erasmus Hall,” [1909].

[54] “September Hockey and Lacrosse Camp,” advertisement, 1933, Box 6, Folder 20, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[55] “September Hockey and Lacrosse Camp,” advertisement, 1933.

[56] Frieda Kitak to Constance Applebee, November 26, 1966, Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[57] Bryn Mawr College Class of 1928 to Constance Applebee, May 19, 1973, Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[58] Mrs. C. Reed Cary to Constance Applebee, Undated, Box 5, Folder 10, Constance Applebee Papers, Bryn Mawr College Archives and Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

[59] “Field Hockey: Number of Participants U.S,” Statista, last modified January 29, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/191655/participants-in-field-hockey-in-the-us-since-2006/.