Vienna E. Soyke

Introduction

The struggle for equality in the United States has been a contentious one, as marginalized groups have clawed desperately for centuries to achieve fair treatment from the so-called “greatest country in the world.” As such, social and political movements are often viewed as distinct and detached from one another. However, this may not be the case, as plentiful activists from diverse groups share overlapping identities, ideologies, and strategies for fighting injustice. Therefore, the idea of “cause and effect” is seemingly hardly a unique aspect when examining history. Dr. Koritha Mitchell, a specialist in African-American literature, has analyzed the connection between the violence that both African-Americans and LGBTQ+ persons have faced in the United States. “I cannot ignore the parallels I see between lynching at the last turn of the century and the violence plaguing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities today. Both forms of brutality emerge from an investment in denying citizenship, and both are designed to naturalize that denial.” Mitchell’s analysis calls our attention to the lessons learned from those in one or both groups from the other, particularly through the treatment by the American criminal justice system.1 Through my research, it is clear that Civil Rights activists outlined specific methods to combat police brutality and disproportionate incarceration rates that would serve as a precedent for movements to follow, specifically the Gay Liberation Movement. Gay rights activists used their tactics to combat similar criminal justice-related issues they faced to achieve equality in their own regard.

Many scholars can agree that the Civil Rights Movement heavily influenced subsequent social movements in the United States, particularly the Gay Rights Movement. Several also agree that the Black Panther Party, in particular, had a heavy influence on the success of following human rights campaigns. Both Black and LGBTQ+ individuals have suffered extensively throughout history at the hands of law enforcement and the American criminal justice system. I would go further, however, to posit that the Black community as a whole set the precedent for the Gay Liberation Front in their dealings with the corrupt criminal justice systems. Numerous incidents indicate similar ideologies. From media representation to police brutality to court systems and incarceration, the LGBTQ+ community pulled the largely instrumental tactics Civil Rights activists used to achieve their desired social and legal progress. Using newspapers, press releases, court cases, and interviews, it is evident that gay rights activists heavily relied upon the tactics and successes of Civil Rights activists to combat the harsh treatment from the American criminal justice system.

Secondary Source Review

“‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’: Community Activism and the Black Panther Party, 1966–1971” by Ryan J. Kirkby, “The American gay rights movement and patriotic protest” by Simon Hall, and “Race Matters: 1968 as Living History in the Black Freedom Struggle” by Jorrit van den Berk and Laura Visser-Maessen all provide valuable background on the African American Civil Rights and Gay Liberation movements.

Ryan J. Kirkby provides excellent insight into several of the specific points I hope to analyze in my research regarding the criminal justice area of the Civil Rights Movement. Further analysis will provide a full exploration of the movement, as Kirkby only focuses on the Black Panther Party in particular. Hall touches on both movements as he discusses the origin of gay rights movements, particularly the legal side of the issue and the famous riot at the Stonewall Inn as a spark for social change.2

Simon Hall details the specifics of the events and protests. However, sometimes, he veers from his topics into other areas, particularly as he touches on movements and effects outside of the United States. Hall’s research provides background information on the Gay Rights Movement to lead into the LGBTQ+’s dealings with law enforcement.3

Jorrit van den Berk and Laura Visser-Maessen explore the gaining traction of the Civil Rights Movement, specifically focusing on 1968. Their first section focuses on the monumental legislation that was achieved this year, like the Fair Housing Act and focuses on school integration. They outline the growing unrest and dissatisfaction with the lack of racial progress in the United States and how this contributed to radical change in the 1960s, leading into the 1970s. They also go on to discuss the idea of being “post-racial” with the Barack Obama and Donald Trump presidencies. The authors argue that the cultures of protest and political activism have been shaped by the events of the Civil Rights Movement of 1968, particularly through the lens of Black activism. They argue that the idea of being content with current racial relations, as well as the opposition to this ideal, can be accredited to the Civil Rights activists’ platforms for change of the 1960s.4

“LOVE IN ACTION Noting Similarities between Lynching Then and Anti-LGBTQ+ Violence Now” by Koritha Mitchell draws connections between the violence both Black and gay Americans faced throughout history. Mitchell discusses the overlap between racism and homophobia, noting prominent figures involved in both. The author notes that violence, in general, is a method to assert power over marginalized groups therefore, lynching and anti-LGBTQ+ violence have similar principles and ideologies. She theorizes the ideological similarities between each group’s victimization and what it means to face violence.5

In “Using Anticarceral Feminism to Illustrate the Impact of Criminalization on the Lives of Individuals in the Sex Trades,” sociologists Moshoula Capous-Desyllas, Deana Payne, and Meg Panichelli look at the criminal justice system’s treatment of individuals involved in the Los Angeles sex trade, including transgender individuals. The authors outline the violence sex workers face, particularly those who are Black and/or LGBTQ+, as they have a disproportionately high rate of involvement in sex work. The authors argue that those who have intersecting identities may face worse discrimination from police. They also argue that the oppression and violence that these individuals have faced is systematic and causes significant lasting damage in multiple areas of their lives.6

Similarly, “The Lavender Scare in Homonormative Times: Policing, Hyper-incarceration, and LGBTQ+ Youth Homelessness” by sociologist Brandon Andrew Robinson examines the disproportionate policing and incarceration rates of LGBTQ+ persons, including youth. The author discusses how these trends especially affect LGBTQ+ people of color and asserts that those of the LGBTQ+ class face higher incarceration rates and how the police force seeks to maintain racial inequality, as well as limit the freedoms of those who deviate from heterosexual norms. Robinson used data and history in this study to explore the social implications of over-policing and hyper-incarceration.7 However, there is room for additional research on not only these implications but also the potential effects of over-policing and incarceration when LGTBQ+ youth become adults, considering the harsh punishments occurring during their formative years.

In examining the learned practices of the Gay Liberation Movement from Civil Rights activists, “‘All of Us Are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutality in the Bay Area” by historian Jared Leighton discusses the connection and cooperation between gay rights leaders and the Black Panther Party. Leighton specifically examines police brutality and the respective groups’ strategies for dealing with each focusing on the San Francisco Bay Area, a known gay haven in the United States. Leighton argues that much of the Gay Rights Movement can (and should) be attributed to the successes and lessons regarding police brutality from the BPP. He cites this statement with examples of “armed self-defense and electoral politics.” This article examines the intersectionality of these movements while also suggesting that social movements of all kinds can be intersectional. This discussion is mainly limited to focusing on the Bay Area rather than addressing the United States as a whole. The Black Panther Party is not the only group of Black people who developed an allyship with the Gay Liberation Front, but rather several Black activist groups that shaped law enforcement-related strategies.8

“The Limits of Legal Discourse: Learning From the Civil Rights Movement in the Quest for Gay and Lesbian Civil Rights” by Odeana R. Neal begins by analyzing the use of violence to achieve legal progress for the respective movements. She also suggests that the use of television expanded the audience of the movements, using it to combat misinformation as well. She insists that gay rights activists used strategies to combat homophobia in general rather than specific legislation to achieve their desired results, similar to Civil Rights activists focusing on eliminating racism. Ultimately, Neal analyzes ideological similarities and belief systems that LGBTQ+ activists adopted from Black activists. This article utilizes media representation as a new platform for activists but lacks emphasis on outlining specific learning experiences rather than belief systems as a whole. Neal provides an extensive summary of each movement, though there is room for additional analysis of a comparison between the two.9

Lastly, in “How the Civil Rights Movement Launched the Fight for LGBTQ+, Women’s Equality”, an interview conducted by Ray Suarez with Yale professor George Chauncy and the University of California, Davis professor Ruth Rosen identifies the 1963 March on Washington, suggesting that it inspired picketing from gay rights activists outside the White House two years later. Chauncy and Rosen also argue that gay rights activists pulled from local organization strategies of Black activists for grassroots movements before the issues saw national attention from politicians. The interviewer and interviewees cite specific examples of similar (or identical) activism strategies.10 Both movements undoubtedly experienced violence and unfair punishments at the hands of the police and the judicial systems. So, while this interview dives deeply into activism strategies, additional exploration of law enforcement can be done to explore the criminal justice side of the movements.

Banding Together Against Police Brutality

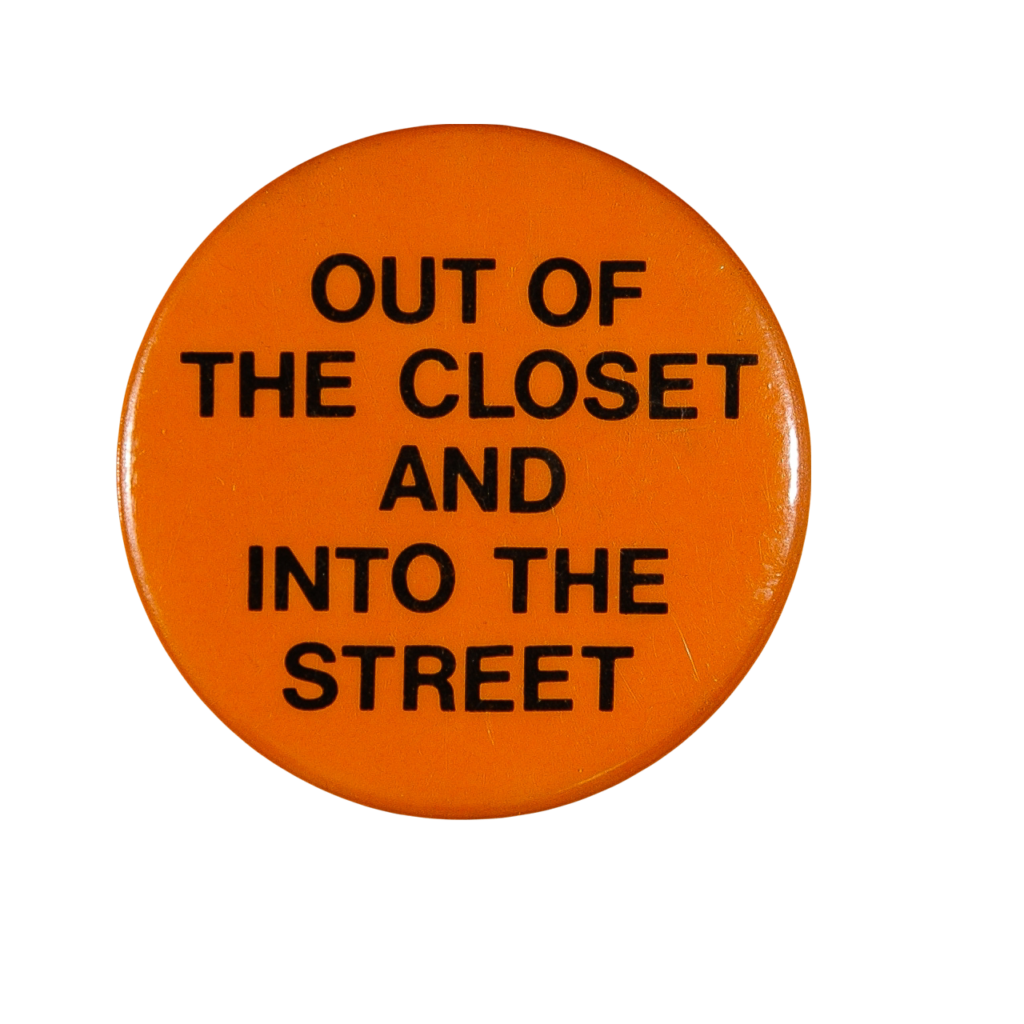

The recent rise of the Black Lives Matter movement has brought police brutality to the forefront of national attention. As examined through the analysis of social media influence, more law enforcement officials are being held accountable for their horrendous treatment of civilians, particularly people of color. Groups of all kinds have come together to support one another in the aftermath of these horrific events, just as the Black Panther Party and gay rights liberation activists did in the 1970s. One of the most infamous police brutality incidents was the raid at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. In response to this horrific event, gay man Carl Wittman, who had previously been a leader of the Students for a Democratic Society, wrote “A Gay Manifesto”. In it, he discusses the safe haven that San Francisco has become for homosexuals, but only out of necessity because of violence taking place everywhere else, both from fellow citizens and law enforcement. Wittman notes, “By the tens of thousands, we fled small towns where to be ourselves would endanger our jobs and any hope of a decent life, we have fled from blackmailing cops, from families who disowned or ‘tolerated’ us; we have been drummed out of the armed services, thrown out of schools, fired from jobs, beaten by punks and policemen.” In the section titled “Oppression”, Wittman emphasizes the methods of entrapment used by law enforcement in baths, bars, and parks to catch gay men in lewd acts. He concludes with several guidelines and goals for the Gay Liberation Movement, the first one being, “Free ourselves: come out everywhere; initiate self-defense and political activity; initiate counter community institutions”.11

In Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton’s famous letter, “To The Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters About The Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements”, he emphasizes the importance of working together with the groups rather than fighting against them. Newton states, “When we have revolutionary conferences, rallies, and demonstrations, there should be full participation of the gay liberation movement and the women’s liberation movement.” He also goes on to say, “We should try to form a working coalition with the gay liberation and women’s liberation groups. We must always handle social forces most appropriately. And this is a significant part of the population, both women and the growing number of homosexuals that we have to deal with.”12

During this time, gay people and Black people were the subjects of severe beatings by police officers. In one instance in Los Angeles, police officers “‘beat, kicked and stomped a man [Howard Efland, alias J. McCann] to death’” upon partaking in homosexual behavior at the Dover hotel.13 Additionally, Berkeley police officers shot and killed a member of the Society for Individual Rights, Frank Bartley, after luring him into advancing onto a male undercover officer. Instances like these and many others allowed for cooperation between the groups in the San Francisco Bay Area and throughout the United States. Black political activist Afeni Shakur spoke about the need for collaboration between the groups at a gay men’s workshop at a Philadelphia convention. A gay man in attendance reported she “began relating to the gay sisters in jail, beginning to understand their oppression, their anger, and the strength in them and all gay people. She talked about how Huey Newton’s statement would be used in the Panther Party, not as a party line, but as a basis for criticism and self-criticism to overcome anti-homosexual hang-ups among party members, and in the black community.”

Through the tireless work of the BPP and the Gay Liberation Movement, government officials, and the Black Panther Party proposed an amendment to create separate police departments in Berkeley, California, in 1970. The proposal consisted of three separate jurisdictions: one for the White community, one for the Black community, and one for campus areas. Each department was supposed to be autonomous but with an agreement on shared facilities.14 Though the amendment was struck down, the newly elected Black mayor promised significant community control over police departments.15

The Black Panther Party’s emphasis on self-defense against police officers also had a major impact on the Gay Liberation movement. In The Black Panther, Huey P. Newton wrote an article in 1967 entitled, “In Defense of Self Defense” in which he states, “The community realizes that force and brutality can only be eliminated by counter force through self-defense.” He went on to cite Malcolm X’s work in saying, “The heirs of Malcolm now stand millions strong on their corner of the triangle, facing the racist dog oppressor and the soulless endorsed spokesmen. The heirs of Malcolm have picked up the gun.”16

A similar call to action can be seen in the Bay Area Reporter article, “A Call for the Essential Gay Revolution” from 1973. Author Reverend Ray Broshears triumphantly states, “As a violent revolutionary has said, it is better to die on your feet than to crawl on your knees to beg for survival. If there is such a thing as Gay Pride in any of you, you will stand up and say, NO MORE, NO MORE. We don’t want a slice of the bread, we want the whole loaf.” He concludes his piece by echoing Black Panther Party ideologies by saying, “The GAY REVOLUTION will not be a violent one, unless someone tries to stifle the work that the GAY ALLIANCE is trying to do, by stopping us with violence.”17

Both groups can be seen placing stress on taking up arms in the face of an oppressive government and police system. The general idea of being “revolutionary,” first begun by the BPP, is utilized to incite passion, action, and participation from marginalized groups as the only acceptable way to make a difference. The Black Panther Party, specifically Huey P. Newton, offers advice and camaraderie with the Gay Liberation Movement, insisting that it is within the party’s values to effect change for this group as well. Gay revolutionaries adhered to this advice through the famous Stonewall riots in which gay people at the New York bar fought back against police raids, eventually causing the bar to go up in flames.18 These actions continue, as witnessed throughout gay newspapers and collaboration between the groups.

Media Influence on Social Activism

Today, more than ever, the media is a crucial tool to spread ideas and movements to the maximum extent possible. Social media especially has had a massive impact on outreach for activists in numerous areas. The “Black Lives Matter” movement gained extensive traction throughout the past ten years, particularly through its use of sites like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. News companies have covered these stories online and on TV. Videos of police brutality can be easily captured via a mobile device like a cell phone, allowing for an increased amount of accountability for law enforcement officers. These videos can be shared in fractions of seconds with people all around the globe. America has also seen increased diversity in television every day, with more Black and gay people being included in numerous shows, commercials, and leadership roles. This is hardly a new phenomenon, however, as this method of advocacy has been present for decades and has only grown as technology has advanced.

This media-centered method for advocacy can be seen largely across many marginalized groups. However, it seems some of the most effective and popularized ones have come from Civil Rights activists. In terms of the media for the Civil Rights Movement, Odeana R. Neal discusses the importance of television, “Nightly viewing of young men and women having dogs set upon them, the almost tangible hostility that was aroused by nine black students’ entering Little Rock Central High School, as well as images of dismal living conditions in Southern rural areas, helped promote the idea that black people were helpless without the beneficence of whites.”19

Media representation has been imperative for advancing social justice movements as a whole. The Montgomery Advertiser describes the advertising methods for the Montgomery Bus Boycott by distributing thousands of mimeographs and typed letters, calling for people to rally behind activists in their efforts. The newspaper also published one of the letters stating, “‘Until we do something to stop these arrests, they will continue. The next time it may be you, or you, or you…We are, therefore, asking every Negro to stay off the busses on Monday in protest of the arrest and trial’”.20 The far-reaching calls to action were a success, as the boycott drew to a close due to the United States Supreme Court ruling in favor of the protesters. The transition was reported as smooth and without violence, which is precisely the type of success that non-violent leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. had hoped for.21 Unfair arrests and trials were significant obstacles for Civil Rights activists, exemplified by the boycott. Rosa Parks served as a figurehead for the movement, and the boycott’s success reached audiences nationwide, ultimately engineering reform for the right to assemble.

In a historic 1963 televised interview, writer and activist James Baldwin called on politicians to make an effective legislative change to combat the horrific treatment of Black Americans, “I think that one who’s got to find some way of putting the present administration of this country on the spot. One has got to force somehow, from Washington, a moral commitment. Not to the negro people.”22 He then went on to discuss the future of Black Americans by saying, “But the Negro in this country…the future of the Negro in this country is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country. It is entirely up to the American people and our representatives…it is entirely up to the American people, whether or not they’re going to face and deal with and embrace this stranger whom they maligned so long.” During his interview, Baldwin cited his experience in the impoverished school system in Harlem, the lack of Black representation in the New York Public School System, an instance of police brutality in which five officers stood on a Black woman’s neck, and the urban renewal taking place in San Francisco, which Baldwin referred to as “moving the Negroes out”. When speaking to the American public, Baldwin used vivid imagery of police beatings and violence through emotion-laden language to make his point clearly and concisely. Black people were being assaulted and murdered. The televised interview was arguably one of the key televised programs to incite reactions (both positive and negative) and allow for numerous politicians to hear his message, with the Civil Rights Act passing just one year later. In certain parts of the country, many Americans were ignorant of the criminal justice’s treatment of Black Americans. A nationwide broadcast of this interview is precisely what was needed to emphasize the extent of the violence taking place. Media is an undoubtedly useful tool, but the added aspect of national television advanced the messages even further. Gay rights activists not only used media-related tactics throughout their movement but also specifically adopted televised strategies that Civil Rights activists like Baldwin used.

The Empty Closet, an LGBTQ+ newspaper out of the University of Rochester, discusses the use (and misuse) of media in the representation and impact of the Gay Liberation Front, which we can also see in Civil Rights Activists campaigning against segregation in the South. The Empty Closet actively campaigned for the removal of harmful ads containing anti-gay language from the local radio station, WBBF. Upon their success in doing so, a follow-up edition of the paper was published on August 10, 1971, noting, “Also, [the manager of the 24-hour store] agreed to carry our newsletters in each of his stores. WBBF also received letters from gay people expressing anger about the ads. As a result, WBBF, who broadcasts a 3-minute spot called ‘Contact,’ invited us on the show…the show will be heard by an estimated 100,000 people.”23 The activists of this paper contributed to altering perceptions of the LGBTQ+ community for a multitude of people in northern New York State. The usage of radio allowed them to publicize their message to approximately 100,000 listeners, even after the radio station had repeatedly allowed ads to use the terms “fag”, “faggot”, and “bull dyke”. This type of verbal discrimination openly allows for prejudice at all levels, whether conscious or subconscious. Viewing LGBTQ+ people as inferior incites violence, both from citizens and law enforcement. Discriminatory language aids directly in harmful laws, unfair sentencing, attacks from law enforcement, and blatant abuse of penal inmates. Advocacy for change often starts in “smaller” areas, such as reforming harmful language. But these changes serve as grassroots movements, effecting amelioration at higher levels, namely, the American government.

Gay rights activists Madeline Davis and Jim Foster similarly utilized the aforementioned television platform at the 1972 Democratic National Convention. During their time to speak, they discussed the necessity for basic human rights to be extended to the gay and lesbian community. Davis detailed the extensive suffering that LGBTQ+ people have undergone as a result of the ongoing bigotry throughout the United States. She emphasized the brutality they have endured due to both fellow civilians and law enforcement alike. She requested that Democrats include anti-discrimination statutes in their platform. Throughout Foster’s speech, he made vehement requests for gay people to be treated as equals. He announced his pride in being a gay man and argued for the liberty to partake in the same emotional relationship that heterosexuals are entitled to.24

The Bay Area Reporter, a gay newspaper out of the San Francisco Bay Area, covered this event thoroughly. Commentator Don Cavallo reviews this monumental event by saying “for the first time in 2000 years, homosexuals were standing up before the world, if you will, and speaking out for the many who have suffered, who are suffering, and who continue to suffer. I cannot tell you the pride I had those few minutes. Pride as a Homosexual American Democrat.”25 Media representation perpetuates further media representation. The Bay Area Reporter has been in existence since 1971. The 1972 Democratic National Convention skyrocketed the number of supporters for the Gay Liberation Front, permitting a further increasing amount of media attention, whether that be television, music, newspapers, or radio.

The impact of this event was extensive, as many households tuned into the Democratic National Convention every four years. Though the anti-discrimination proposal was not enacted initially, in 2012, the Democratic Party officially added marriage equality to its platform. Davis also went on to conduct an interview with Playboy Magazine in 1973 and meet her long-term partner (and eventually wife) in 1974.26 Madeline Davis served as a prominent figurehead for decades because of her speech at the Democratic National Convention, advocating for gay rights to be added to the Democratic Party platform consistently. The televised speech aided as a catalyst for her political career in the advocacy for those within her community.

While the effects may not have been immediate, if it was not for Davis’ and Foster’s bravery to lecture on national television, equal rights and protection for the LGBTQ+ community may have taken much longer. Perhaps some of their motivations and hopes for success can be attributed to people like James Baldwin. Campaigning locally is undoubtedly important, but before an age of easily accessible social media platforms, television was the superior outreach method.

Before Baldwin’s interview, he had met with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to discuss the condition of Black equality and Civil Rights in the United States. Just as Madeline Davis had met with numerous members of the Democratic Party, it is easy to see that contact with politicians combined with media attention and recognition serves social movements incredibly well. Discrimination towards those who are different often derives from a lack of understanding. In this regard, seeing well-spoken, well-respected homosexuals on television assuaged many fears and distastes toward the community. Homosexuals were not sexually deviant, immoral criminals. They were everyday people who simply wanted to live the same lives as everyone else. They were not deserving of police raids, harsher prison sentences, or being excluded from freedoms that heterosexual individuals enjoyed. They deserved respect and equal treatment.

Similar results occurred following Black media representation. Black Americans were just Americans desiring to live harmoniously with their White brothers and sisters. They wanted what they were promised in the Bill of Rights, namely fair trials by jury and freedom from cruel and unusual punishments. Black Americans demonstrated that this type of change was not only possible but necessary. Education and representation through the media was an unparalleled platform in which they could reach wider audiences without being uninterrupted or censored. Simply existing in a public space was effective in its own right. Even in predominantly White spaces, Black Americans still existed on television, radio, and in newspapers. They made it clear they were not going away and that they would not stop until they had achieved their desired results. The tool of journalism and the press was crucial in their fight. Black Civil Rights activists popularized this media-centered methodology, opening the doors for social movements to follow.

Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System

The other half of the criminal justice system involves sentencing, court systems, and incarceration. In the same ways that LGBTQ+ and Black people have experienced maltreatment at the hands of law enforcement, they faced similar discrimination within American courts. People of color (specifically Black and Brown Americans) have faced disproportionate imprisonment rates for centuries. The same has also been true for lesbian, gay, and bisexual people, as they are “three times more likely to experience incarceration than the general population”. The intersectionality rates are astonishingly higher, with approximately half of Black transgender Americans having been imprisoned in their lifetime. Treatment within penal institutions has often gone unregulated, with corrections officers and other prison staff turning a blind eye to the overt violence inflicted upon Black, Brown, and LGBTQ+ people by other inmates and/or contributing to the assaults. This type of conduct toward Black LGBTQ+ persons is not exclusive to incarceration, however. There are numerous recorded instances of individuals facing threats of court order violations based on their gender identities and expressions during court-mandated recovery programs.27 Civil Rights activists have used these concerted efforts to combat these horrendous sentences and conditions, many of which can be observed in the 1970s and 1980s by the Gay Liberation Front.

One of the strategies Black activists used was fundraising for inmates believed to have received unfair treatment or sentences. In an article published by the Black Panther Party, the author advertised a fundraising campaign for two Black inmates jailed for murder. Both were set to receive the death penalty. The Black Panther Party used the money to fund a competent attorney, as the inmates themselves could not afford one. The author of the piece also outlines the unfair trial of the two defendants, in which there were no Black jury members. They also alleged that key witnesses made harmfully irrelevant remarks such as “all Negroes look alike to me!” and Black spectators were removed from the courtroom under the premise of intimidating witnesses, despite remaining silent. The newspaper provides contact information for attorneys willing to take on the case as well as an address for donations.28

In a 1987 issue of the Bay Area Reporter, the paper published an ad for the screening of a documentary presented by the AIDS Action Pledge and Names Project. All admission donations for the fund titled, “Send Terry Blankenship To Court, Not To Prison, Fund” would go toward legal finances for lesbian Terry Blankenship, who was facing charges of trespassing during a protest at the Supreme Court. Blankenship provided a statement within the article, in which she asserts that anti-LGBTQ+ laws contributed to the growing violence against gay people and deliberate ignorance toward the AIDS epidemic. The author discussed Blankenship’s need for financial assistance to travel back to Washington D.C., in time for her court date. If she were not able to do so, a warrant would be put out for her arrest.29

Legal defense funds (LDFs) have also been utilized extensively by both groups in efforts to finance trials and resources for individuals facing charges. The first and most notable civil and human rights law organization is the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, organized under Thurgood Marshall in 1940.30 The LDF raised money regularly for various Black Americans facing charges, including the 1948 murder case involving Black woman, Rosa Lee Ingram. According to the Arkansas State Press, she, along with her two sons, was initially sentenced to death for the murder of a White sharecropper. The White farmer threatened Ingram and her sons with a rifle when several of their farm animals escaped the property. Her sons came to defend their mother in fear of the farmer murdering her, ultimately resorting to a heavy blow to the farmer’s head. The NAACP protested her death sentence and organized a defense fund for her case, partnering with her defense attorney to appeal their conviction, and the sentence was later changed to life in prison.31 After twelve years in prison, the Ingrams were freed from imprisonment due to the efforts of the NAACP and other notable campaigns from communities across the country.32

The gay community also developed its legal defense fund in 1973, following suit of the NAACP. The organization, Lambda Legal, is an organization that fights for the civil rights of the LGBTQ+ community, as well as those impacted by AIDS. Their formal statement currently notes, “As a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, we do not charge our clients for legal representation or advocacy, and we receive no government funding. We depend on contributions from supporters around the country.”33 In one of their first cases, Gay Student Organization v. Bonner, Lambda Legal aided the Gay Student Organization of the University of New Hampshire in their fight for permission to host sponsored social events for their club on campus.34 Initially, events went on as planned, but after backlash from the public and criticism from the New Hampshire governor, the university placed a ban on the organization’s social events and the distribution of “homosexual literature.” The president of the university, Thomas N. Bonner, then threatened to suspend the organization as a whole if such activities continued. Due to the aid and funding from Lambda Legal, the United States District Court for the District of New Hampshire ruled that the students were protected under the First Amendment, even on a university campus. Under this ruling, the university was required to grant the Gay Student Organization the same freedoms as every other campus organization.

Civil Rights Activists and Gay Rights Activists have also sought to conquer prison abuse, which seemed to have occurred at a much higher rate, particularly for feminine gay men and transgender individuals.35 In one instance in 1948, the NAACP protested the Texas governor’s allowance for indecent prison conditions as well as alleged prisoner abuse that occurred regularly, according to an anonymous letter on behalf of 300 inmates at the Texas State Prison.36 The letter stated that Black prisoners were regularly beaten, denied medical treatment, forced to work in horrendous conditions, and fed seemingly inedible food. The governor publicly responded to ensure that reform would occur, including fair treatment of prisoners, regardless of race, and that the facilities would be updated.

Later, in 1971, the Seattle National Committee to Combat Fascism (NCCF) sent a team of medical personnel to the Walla Walla State Prison in Washington State. They arrived upon the request of the inmates, a majority of whom were Black, to administer sickle cell anemia tests, according to The Black Panther.37 The conditions of the prison, when they arrived, were abhorrent, with many inmates pictured with infected bedsores. It was also revealed that one of the prison doctors was neurologically impaired due to previous brain surgery, while another had a severe and debilitating drug addiction. Both of these doctors were still treating patients. The NCCF tested and treated over 180 inmates for sickle cell anemia and numerous other health conditions during their visit.

Activists also later developed several organizations to cease the neglect and abuse of LGBTQ+ prisoners. One such organization, Stop Gay Rape in Prison (SGRIP), sought to protect gay inmates from being preyed upon by “straight” inmates in 1982.38 In 1994, activists from San Francisco met with Assembly maker Phil Isenberg to discuss California prison conditions.39 Their main concern was to highlight a severe lack of HIV/AIDS treatment for inmates, as well as over 100 grievous human rights violations alleged to have taken place within the institutions. While HIV/AIDS is not exclusively a disease of homosexuals and transgender individuals, it can be presumed that much of the medical neglect and malpractice could be attributed to a purposeful lack of education and government funding due to the taboo and misconceptions of the virus.

Civil Rights activists set the precedent for inmate advocacy using numerous legal, protesting, and financial methods. The Gay Liberation Front followed suit soon thereafter, as the types of maltreatment within prisons of Black Americans often overlapped with that of LGBTQ+ inmates. The methods executed by Black activists were partially successful in effecting change, though there are still many problems within prison systems today. Marginalized individuals who find themselves incarcerated are still subject to significant discrimination within penal institutions. This does not negate the progress achieved at the time, however. The notoriety and achievements served as a starting point and model for other marginalized groups, as they presented attainable techniques to serve those within their communities, even from behind bars.

Conclusion

The Civil Rights Movement was one of the first of its kind. It received the most media coverage, challenged perceptions of nationality and skin color, and facilitated major legislative and social change. The leaders acted as role models for those who differed from traditional straight, White, masculine norms. Through their perseverance and accomplishments, they inspired other outcast communities to stand up for themselves in the areas they received injustice. They challenged the very idea of what it meant to have rights as an American citizen, including the rights of those suffering at the hands of the corrupt criminal justice system. Black activists served as exemplars for the LGBTQ+ community to challenge their mistreatment by police and prison systems. Their mechanisms for change operated both directly and indirectly to demonstrate an unwillingness to accept the status quo and that every American is entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Footnotes

- Koritha Mitchell, “Love in Action: Noting Similarities between Lynching Then and Anti-LGBT

Violence Now,” Callaloo 36, no. 3, (Summer 2013): 688-717, doi:10.1353/cal.2013.0167. ↩︎ - Ryan Kirkby, “‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’: Community Activism and the Black Panther Party, 1966-1971,” Canadian Review of American Studies 41, no. 1 (March 2011): 25, doi:10.3138/cras.41.1.25. ↩︎

- Simon Hall, “The American Gay Rights Movement and Patriotic Protest,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19, no. 3 (September 2010): 536. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A238194368/LitRC?u=ycp_main&sid=summon&xid= 2b5fcc26. ↩︎

- Jorrit van den Berk and Laura Visser-Maessen, “Race Matters: 1968 as Living History in the Black Freedom Struggle.” European Journal of American Studies 14, no. 1 (2019): 22, doi.org/10.4000/ejas.14233. ↩︎

- “Love in Action: Noting Similarities between Lynching Then and Anti-LGBT Violence Now.” Callaloo 36, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 688. doi:10.1353/cal.2013.0167. ↩︎

- Moshoula Capous-Desyllas, Deana Payne, and Meg Panichelli, “Using Anticarceral Feminism to Illustrate the Impact of Criminalization on the Lives of Individuals in the Sex Trades.” Affilia 36, no. 4 (November 2021): 532, https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109920978565. ↩︎

- Brandon A. Robinson, “The Lavender Scare in Homonormative Times: Policing, Hyper-Incarceration, and LGBTQ Youth Homelessness.” Gender & Society 34, no. 2 (April 2020): 210, https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220906172. ↩︎

- Jared Leighton, “‘All of Us are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutality in the Bay Area,” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019): 860, 10.1093/jsh/shx119. ↩︎

- Ordeana R. Neal, “The Limits of Legal Discourse: Learning From the Civil Rights Movement in the Quest for Gay and Lesbian Civil Rights,” University of Baltimore School of Law (1996): 1. https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/449/. ↩︎

- George Chauncy and Ruth Rosen, “How the Civil Rights Movement Launched the Fight for LGBT, Women’s Equality,” interview by Ray Suarez PBS NewsHour, September 7, 2013, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/ civil-rights-launched-the-fight-for-lgbt-women-s-equality#story. ↩︎

- Carl Wittman, “A Gay Manifesto,” in America in the Sixties–Right, Left, and Center: A Document History, ed. Peter B. Levy (Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1998), 213. ↩︎

- Huey P. Newton, “To The Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters About The Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements” (letter presented in New York City, August 15, 1970. http://www.back2stonewall.com/tag/forgotten- gay-history-august-1970-read-black-panthers-leader-huey-newtons-pro-gay-rights-letter. ↩︎

- “Death at the Dover; Witnesses Say Vice Cops Beat Man to Death,” Los Angeles Advocate, (April 1969), 2, quoted in Jared Leighton, “‘All of Us are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutality in the Bay Area,” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019): 860, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shx119. ↩︎

- Black Panther Party, Whose Law? Whose Order? Control your local police: Summary of Berkeley Police Control Amendment (Berkeley, California, 1971). ↩︎

- Jared Leighton, “‘All of Us are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutality in the Bay Area,” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019): 860, 10.1093/jsh/shx119. ↩︎

- Huey P. Newton, “In Defense of Self Defense,” The Black Panther, July 3, 1967, https://www.marxists.org/archive/newton/1967/07/03.htm. ↩︎

- Ray Broshears, “A Call for the Essential Gay Revolution,” Bay Area Reporter, May 16, 1973. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=BAR19730516.1.37&e=——-en–20-BAR-1-byDA-txt-txIN-guns——-1. ↩︎

- “Stonewall riots,” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 21, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/event/Stonewall-riots. ↩︎

- Ordeana R. Neal, “The Limits of Legal Discourse: Learning From the Civil Rights Movement in the Quest for Gay and Lesbian Civil Rights,” University of Baltimore School of Law (1996): 1. https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/449/. ↩︎

- Joe Azbell, “Negro Groups Ready Boycott Of City Lines,” The Montgomery Advertiser, December 4, 1955, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/47031015/article-about-the-planning-of-the-montgo/. ↩︎

- “Negroes End Montgomery Bus Boycott: Desegregation Starts Smoothly,” The Eugene Guard, December 21, 1956, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53631825/montgomery-bus-boycott-ends-and/. ↩︎

- “A Conversation With James Baldwin,” interview by Kenneth Bancroft Clark, WGBH Educational Foundation, May 24, 1963, http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-0v89g5gf5r. ↩︎

- “The Bi-Weekly Newsletter of the University of Rochester Gay Liberation Front: ‘Fag’ Ads Off, GLF On” The Empty Closet, August 10, 1971, http://www.lib.rochester.edu/IN/RBSCP/Databases/Attachments/Closet/1971/ 1971_AUGUST_10.pdf. ↩︎

- Madeline Davis and Jim Foster, “Gay Rights Minority Report,” (speech presented at the 1972 Democratic National Convention), Miami, Florida, July 12, 1972, https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/lgbtq_interviews/8/. ↩︎

- Don Cavallo, “Commentary,” Bay Area Reporter, July 26, 1972, https://archive.org/details/BAR_19720726/page/ n27/mode/2up?view=theater. ↩︎

- Annabelle Williams, “Madeline Davis, Who Spoke to the Nation as a Lesbian, Dies at 80,” The New York Times, June 18, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/18/us/madeline-davis-dead.html?smid=url-share. ↩︎

- Brandon A. Robinson, “The Lavender Scare in Homonormative Times: Policing, Hyper-Incarceration, and LGBTQ Youth Homelessness.” Gender & Society 34, no. 2 (April 2020): 210, https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220906172. ↩︎

- Andre Dale, Al McGhee, and Opal Ellis, “The Taylor-Chatman Incident,” The Black Panther (Oakland, California), March 6, 1971, https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/06%20no%206%201-20%20 mar%206%201971.pdf. ↩︎

- “Action Pledge to Help Protester Keep Court Date,” Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), November 19, 1987, https://archive.org/details/BAR_19871119/mode/2up?q=prison+fund&view=theater. ↩︎

- “History: We are the Country’s First and Foremost Civil and Human Rights Law Firm,” NAACP Legal and Educational Fund, Inc., accessed April 10, 2022, https://www.naacpldf.org/about-us/history/. ↩︎

- “NAACP To Appeal Death Sentence Of Georgia Woman And Her Sons,” Arkansas State Press (Little Rock, Arkansas), February 27, 1948, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12F3CB549363AB38%40EANAAA-13396335B740BEB0%402432609-13395A9B163D5430%400-137E27CC184AC9F2%40NAACP%2BTo%2BAppeal%2BDeath%2BSentence%2BOf%2BGeorgia%2BWoman%2BAnd%2BHer%2BSons. ↩︎

- “Mrs. Ingram and Sons Free.” Los Angeles Tribune, September 11, 1959, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A129280BA5DFE7A33%40EANAAA-12C5FE30F190C050%402436823-12C5FE311155C268%403-12C5FE31ADD68EE0%40Mrs.%2BIngram%2Band%2BSons%2BFree. ↩︎

- “Lambda Legal History,” Lambda Legal, accessed April 10, 2022, https://www.lambdalegal.org/about-us/history. ↩︎

- Gay Students Organization of University of New Hampsire v. Bonner, 509 F.2d 652 (1st Cir. 1974). https://casetext.com/case/gay-students-org-of-univ-of-new-h-v-bonner/. ↩︎

- Brandon A. Robinson, “The Lavender Scare in Homonormative Times: Policing, Hyper-Incarceration, and LGBTQ Youth Homelessness.” Gender & Society 34, no. 2 (April 2020): 210, https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220906172. ↩︎

- “Treatment of Texas Prisoners Protested,” Arkansas State Press (Little Rock, Arkansas), February 20, 1948, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12F3CB549363AB38% 40EANAAA-13396333825F1610%402432602-13395A89E19C374B0%400-137E27BE5D6D4BEC%40Treatment% 2Bof%2BTexas%2BPrisoners%2BProtested. ↩︎

- “Seattle N.C.C.F. Medical Corps Treats Walla Walla Prison Inmate.” The Black Panther (Oakland, California), March 6, 1971. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/06%20no%206%201-20%20mar%206% 201971.pdf. ↩︎

- David Ewing,“A message from the inside world.,” Blacklight (Washington D.C.), January 1, 1982. http://hdl. handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:283871. ↩︎

- Marghe Covino,“SF Activists Discuss PWA Prison Abuse With Assemblyman,” Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), June 16, 1994, https://archive.org/details/BAR_19940616/mode/2up?q=prison+abuse&view= theater.

↩︎

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“Action Pledge to Help Protester Keep Court Date.” Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), November 19, 1987. https://archive.org/details/BAR_19871119/mode/2up?q=prison+fund&view=theater.

Azbell, Joe. “Negro Groups Ready Boycott Of City Lines.” The Montgomery Advertiser. December 4, 1955. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/47031015/article-about-the-planning-of-the-montgo/.

Baldwin, James. “A Conversation With James Baldwin.” Interview by Kenneth Bancroft Clark. WGBH Educational Foundation, May 24, 1963. http://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip-15-0v89g5gf5r.

Broshears, Ray. “A Call for the Essential Gay Revolution.” Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), May 16, 1973.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=BAR19730516.1.37&e=——-en–20-BAR-1-byDA-txt-txIN-guns——-1.

Cavallo, Don. “Commentary.” Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), July 26, 1972. https://archive.org/details/BAR_19720726/page/n27/mode/2up?view=theater.

Covino, Marghe. “SF Activists Discuss PWA Prison Abuse With Assemblyman.” Bay Area Reporter (San Francisco, California), June 16, 1994. https://archive.org/details/BAR_19940616/mode/2up?q=prison+abuse&view=theater.

Dale, Andre, Al McGhee, and Opal Ellis. “The Taylor-Chatman Incident.” The Black Panther (Oakland, California), March 6, 1971. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/06%20no%206%201-20%20mar%206%201971.pdf.

Ewing, David. “A message from the inside world.” Blacklight (Washinton D.C.), January 1, 1982. http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:283871.

“Mrs. Ingram and Sons Free.” Los Angeles Tribune, September 11, 1959, https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A129280BA5DFE7A33%40EANAAA-12C5FE30F190C050%402436823-12C5FE311155C268%403-12C5FE31ADD68EE0%40Mrs.%2BIngram%2Band%2BSons%2BFree.

“Montgomery Bus Boycott: Desegregation Starts Smoothly.” The Eugene Guard. December 21, 1956. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53631825/montgomery-bus-boycott-ends-and/.

“NAACP To Appeal Death Sentence Of Georgia Woman And Her Sons.” Arkansas State Press (Little Rock, Arkansas), February 27, 1948.https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12F3CB549363AB38%40EANAAA-13396335B740BEB0%402432609-13395A9B163D5430%400-137E27CC184AC9F2%40NAACP%2BTo%2BAppeal%2BDeath%2BSentence%2BOf%2BGeorgia%2BWoman%2BAnd%2BHer%2BSons.

“Negroes End Davis, Madeline and Jim Foster. “Gay Rights Minority Report.” Speech presented at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, Miami, Florida, July 12, 1972. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/lgbtq_interviews/8/.

Newton, Huey P. “In Defense of Self Defense.” The Black Panther (Oakland, California), July 3,1967. https://www.marxists.org/archive/newton/1967/07/03.htm.

Newton, Huey P. “To The Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters About The Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements.” Letter presented in New York City, August 15, 1970. http://www.back2stonewall.com/tag/forgotten-gay-history-august-1970-read-black-panthErs-leader-huey-newtons-pro-gay-rights-letter.

“Seattle N.C.C.F. Medical Corps Treats Walla Walla Prison Inmate.” The Black Panther (Oakland, California), March 6, 1971. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/black-panther/06%20no%206%201-20%20mar%206%201971.pdf.

“The Bi-Weekly Newsletter of the University of Rochester Gay Liberation Front: ‘Fag’ Ads Off, GLF On.” The Empty Closet (Rochester, New York), August 10, 1971. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/IN/RBSCP/Databases/Attachments/Closet/1971/1971_AUGUST_10.pdf.

“Treatment of Texas Prisoners Protested.” Arkansas State Press (Little Rock, Arkansas), February 20, 1948.https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12F3CB549363AB38%40EANAAA-13396333825F1610%402432602-13395A89E19C374B0%400-137E27BE5D6D4BEC%40Treatment%2Bof%2BTexas%2BPrisoners%2BProtested.

Wittman, Carl. “A Gay Manifesto,” in America in the Sixties–Right, Left, and Center: A Document History, edited by Peter B. Levy, 213-18. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 1998.

Secondary Sources

Capous-Desyllas, Moshoula, Deana Payne, and Meg Panichelli. “Using Anticarceral Feminism to Illustrate the Impact of Criminalization on the Lives of Individuals in the Sex Trades.” Affilia 36, no. 4 (November 2021): 511–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109920978565.

Chauncy, George and Ruth Rosen. “How the Civil Rights Movement Launched the Fight for LGBT, Women’s Equality,” interview by Ray Suarez PBS NewsHour, September 7, 2013. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/civil-rights-launched-the-fight-for-lgbt-women-s-equality#story.

“Death at the Dover; Witnesses Say Vice Cops Beat Man to Death,” Los Angeles Advocate, (April 1969): 2. Quoted in Leighton, Jared. “‘All of Us are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutalityin the Bay Area.” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019): 860-865,10.1093/jsh/shx119.

Hall, Simon. “The American Gay Rights Movement and Patriotic Protest.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19, no. 3 (September 2010): 536–562.https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A238194368/LitRC?u=ycp_main&sid=summon&xid=2b5fcc26.

Kirkby, Ryan J. “‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’: Community Activism and the Black Panther Party, 1966-1971.” Canadian Review of American Studies 41, no. 1 (March 2011): 25–62. doi:10.3138/cras.41.1.25.Lambda Legal. “Lambda Legal History.” Lambda Legal. Accessed April 10, 2022. https://www.lambdalegal.org/about-us/history.

Leighton, Jared. “‘All of Us are Unapprehended Felons’: Gay Liberation, the Black Panther Party, and Intercommunal Efforts Against Police Brutality in the Bay Area.” Journal of Social History 52, no. 3 (2019): 860-865, 10.1093/jsh/shx119.

Mitchell, Koritha. “Love in Action: Noting Similarities between Lynching Then and Anti-LGBT Violence Now.” Callaloo 36, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 688-717. doi:10.1353/cal.2013.0167.NAACP LDF. “History: We are the Country’s First and Foremost Civil and Human Rights Law Firm.” NAACP Legal and Educational Fund, Inc. Accessed April 10, 2022. https://www.naacpldf.org/about-us/history/.

Neal, Odeana R. “The Limits of Legal Discourse: Learning From the Civil Rights Movement in the Quest for Gay and Lesbian Civil Rights.” University of Baltimore School of Law (1996): 1–41. https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/449/.

Robinson, Brandon Andrew. “The Lavender Scare in Homonormative Times: Policing, Hyper-Incarceration, and LGBTQ Youth Homelessness.” Gender & Society 34, no. 2 (April 2020): 210–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220906172.

Rountree, Emma. “Rosa Lee Ingram Case.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Apr 14, 2021. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/rosa-lee-ingram-case/.

“Stonewall Riots.” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 21, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/event/Stonewall-riots.

van den Berk, Jorrit and Laura Visser-Maessen. “Race Matters: 1968 as Living History in the Black Freedom Struggle.” European Journal of American Studies 14, no. 1 (2019): 1-22, doi.org/10.4000/ejas.14233.

Williams, Annabelle. “Madeline Davis, Who Spoke to the Nation as a Lesbian, Dies at 80.” The New York Times. June 18, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/18/us/madeline-davis-dead.html?smid=url-share.